by Diana Sette, as originally published in Permaculture Design magazine

What is “permaculture,” anyway? Maybe you hear people talking about it all the time, and still have no idea what it is. Maybe someone loosely recommended to you that you check it out, because it might interest you. Maybe picking up this magazine is the first time you are seeing the word. Whatever brought you to this point, I can assure you that there is something in permaculture for you. I can also assure you that even for many permaculture practitioners, it can be challenging to pin down in a quick ‘elevator speech’ what exactly permaculture is. Some say it’s a movement; some say it’s a collection of growing methods; some say it’s philosophy. In this article, we will focus on permaculture as a design system. During my Permaculture Teacher training course, our teachers challenged us to take five minutes to come up with a definition for permaculture. Some people came up with it quickly—some needed more time.

Overall, the variety of definitions painted a colorful array of nuances and subtleties. Hopefully, this article will leave you with a clearer sense of what is permaculture, with ways in which you may be able to take the next steps on your journey.

Beginnings

First, let me break the word “permaculture” down for you. “Perma:” short for “permanent.” “Culture:” short for “agriculture” and also “culture.” So you can think of “permaculture” as simply “permanent agriculture” and “permanent culture.” We don’t mean “permanent” in the sense of unchanging, but rather in the sense of a deep sustainability. The term was coined and popularized in the mid-70s by two Australian ecologists, Bill Mollison (1) and his young student, David Holmgren (2). “Permaculture” is now a term understood on a global scale.

Contrary to what our digitized and mechanized culture may present at times, humans rely on the land. Our ability to survive rests wholly on plants’ ability to capture the sun’s energy and translate it into a form useable to us through photosynthesis. From the land, we create our food, shelter, water, and clothing—and also our culture. Traditionally, human cultures centered on the seasonal rhythms and cycles of the earth. Observing that the world has grown alienated and disconnected from our intimate relationship with the earth, permaculture looks to re-center our systems (be it food, economic, political, etc.) in the flow of energy and the cycles of nature.

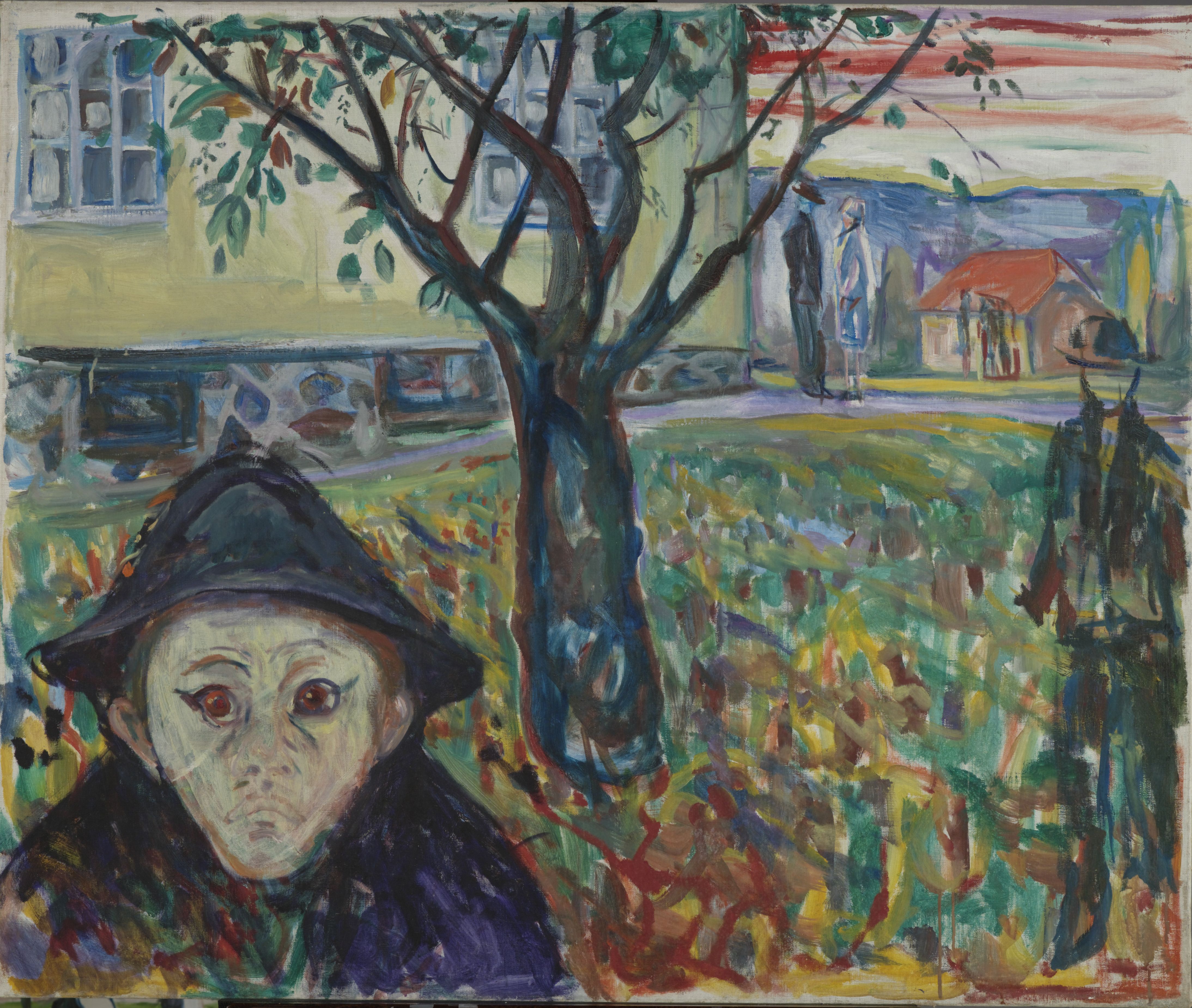

Calendula seed abundant in regeneration.

Calendula seed abundant in regeneration.

As we face extreme global catastrophes—climate change, war, and hunger, among others—we can see that if human societies do not change course, we will perish, and the earth will continue to adapt and go on without us. Therefore, the more we work with the earth, learn from her natural cycles, and model human systems on ecological models of adaptability and resiliency, we can better weather the storm to create a permanent and resilient culture. Permaculture proposes this approach.

More than fancy gardening

Permaculture is a holistic, ecological design system that can be applied to everything from urban planning to rural land design, from economic systems to social structures, and everything in between. It is not only one set of practices, or a philosophy—it is a way of integrated thinking, using a set of design principles to work with nature’s energy. This ecological perspective sees the world as a complex web, rather than as a complicated series of segregated events or discrete elements. The design system can produce a paradigm shift that may be comforting and inspiring to those who feel as if they are constantly putting energy into a system (whether it’s their home garden, farm, political, social, or economic work) that never seems to change or offer much of a yield as compared to the input. Permaculture is a way of designing the world we want that cares for the earth and people so that all needs are met in an equitable way. Permaculture design is abundant systems thinking, and prevents the constant banging of one’s head against the wall when faced with supposed constant scarcity. Because the point is that by working with rather than working against natural forces, one can minimize inputs and harvest maximum outputs. It’s a simple idea at first glance. Yet, it is an integrated system with many facets—anything can be viewed through a permaculture design lens.

The Permaculture Design Course (PDC)

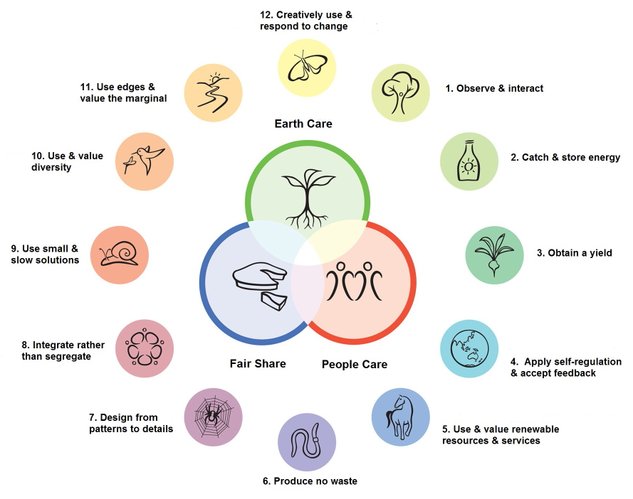

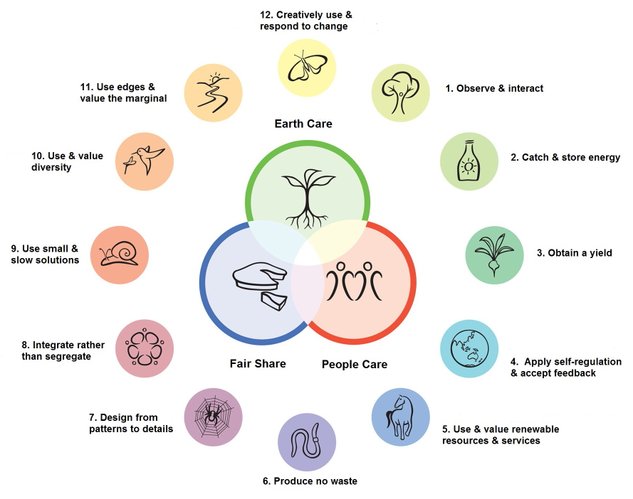

As an integrated design system, permaculture incorporates numerous disciplines of study and practice. These disciplines are presented in a PDC resulting in a certification as a Permaculture Designer (3). Because of the numerous systems in which these design principles can be applied, the PDC covers a sort of introductory buffet to design topics that emphasize the core ethics: Earth Care, People Care, and Fair Share.

Each PDC covers Introduction to Permaculture Ethics, Meta-systems, Permaculture Principles, Pattern Language, Design Methods (site analysis and observation, zones, and sectors), Natural Systems, Climate & Biogeography, Ecosystems & Ecology, Earthworks/land forms, Water, Soils (microbiology, remediation, regenerative practices, compost, carbon sequestration), Forest (tree and mushroom cultivation), Arid & Tropical Regions, Cultivated Systems, Home Systems (root cellars, medicinal herbs), Microclimates, Building Design (natural building, energy efficiency), Greenhouses, Forest Gardening, Aquaculture, Agroforestry (alleycropping, forest farming, riparian buffers, silvopasture, windbreaks), Seed-saving, Waste Treatment (grey and blackwater, humanure),

Composting outhouse in Vermont that helps to cycle nutrients on-site.

Composting outhouse in Vermont that helps to cycle nutrients on-site.

Energy, Appropriate Technology & Tools, Livestock (pasture management, holistic animal care), Social Systems, Urban/Rural/Suburban Ecologies, Community Design, Economics (local, slow, and regenerative), Invisible Structures (governance structures, personal patterns), Broadscale Farming & Land Use (keyline design, land trusts), and Ecological Restoration & Wildlife.

The standard PDC is an intensive 72-hour course, sometimes split into two separate weeks or several weekends. Various teachers emphasize different subjects, but all PDCs should touch on all the above.

Daniel and Rosemary checking out an aquaponic system in action at Seedfolk City Farm (http://seedfolkcityfarm.org) an urban youth farm in Rochester, NY.

Daniel and Rosemary checking out an aquaponic system in action at Seedfolk City Farm (http://seedfolkcityfarm.org) an urban youth farm in Rochester, NY.

Considering that any one of these topics warrants a life study (!), there are numerous entry points to design resilient systems. A PDC is a way to step outside your daily life and take a fresh look at an expansive array of topics. Permaculture marries indigenous ways of knowing with regenerative agriculture, modern green infrastructure, and progressive socio-politico-economic structures.

Permaculture is a process of looking at the whole, seeing what the connections are between the different parts, and assessing how those connections can be changed (4) so that relationships function more harmoniously.

But where to start?

My advice to someone just dipping their toes into the permaculture ocean? Get a lay of the land, observe what themes and topics attract you, and then walk toward them. Don’t try and figure it all out at once. Start small and build on your successes. Ask lots of open-ended questions and listen with curiosity. A few tips…

1. Get rooted in permaculture principles and ethics. David Holmgren presented the 12 Design Principles as the petals of a cyclical flower (5).

These guiding principles can be adapted to any systems thinking. Ethics are core, as People Care may seem simple, yet lead us into a deeper journey of unlearning and teaching ourselves new communication patterns and listening skills—or rethinking urban planning to be centered on the real needs of human beings. This is perhaps the area that continues to expand the most and require the most experimentation and feedback, as every city, town, neighborhood, street, house, and bedroom has its own social microclimate, and healthy social ecosystem models and patterns are myriad (6). Earth Care has perhaps gained the most attention and focus, at times creating the misconception that permaculture is just a set of practices, rather than a way of approaching a problem. Nevertheless, permaculture has a lot to offer in food growing and land stewardship. Finally, Fair Share is the third essential piece of permaculture, teaching us to be aware of the existing yield in front of us and to know when we have enough, but also to act ethically to distribute surplus resources when our ‘cup runneth over.’

2. Attend a PDC, read everything you can about permaculture, listen to podcasts, and visit working permaculture sites. A PDC can be like a trip down a rabbit hole that leaves the sojourner wanting more at the end. It is one of the best ways to get significant exposure to what’s possible with permaculture. Studying permaculture through reading (7) will help you gain more clarity to know where you want to dive in more deeply. For many people, simply spending time in a place that is a thriving permaculture model leads to tremendous shifts.

3. Find what interests you most and work from your niche. Evaluate your strengths. What existing assets and resources are already present? Use that as your starting point. What interests you? How do those interests overlap with the needs of your community? From there, take the smallest steps possible to make the biggest impact on existing systems. Maybe that means meeting your neighbors, planting perennial onions, saving seeds to plant out the next year, collecting rainwater off your roof, getting involved with or starting a food cooperative, building a humanure composting system on your property, or simply recording patterns where you are working for a year or more. Whatever your entry point, make sure to take a step back and observe the social, biological, and economic ecosystems and listen for feedback before taking the next actions. That is our civic duty as residents and stewards of this earth and of our communities: listen and accept feedback.

4. Finally, walk the walk, and work to establish good working demonstration sites. Starting with one or two systems that are manageable is wise so that you don’t become overwhelmed. In modern society, we have grown quite ignorant of energy systems, and by creating these working systems that demonstrate that there is no free lunch in ecological systems—something always comes from somewhere, and waste is food for something else—we can demonstrate a new paradigm in action (8). Share replicable systems with those who are interested, and focus your energy on creating a world we want, rather than being drained by fighting against systems that are broken. As Buckminster Fuller puts it, “you never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

As one of my permaculture teachers, Peter Bane, tossed out in a PDC class one day while reflecting on ancient Viking culture, “it’s better to adapt than die.” I will add to that: better than not dying is thriving! And I think permaculture design principles and ethics present a way to rethink our current social, political, economic, and agricultural systems with new eyes embracing the transformation to thriving whole communities of abundance. ∆

Notes

1. Mollison, Bill. Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual.

2. Holmgren, David. Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability.

3. One can learn more about the standardization of PDC certification and accreditation from the Permaculture Institute of North America (pina.in), the Permaculture Institute of the Northeast (northeastpermaculture.org), or the Permaculture Institute (www.permaculture.org/what/certificate/). Also, look in the back of Permaculture Design magazine for listings of upcoming PDCs and workshops.

4. Whitefield, Patrick. What is Permaculture?

5. Holmgren, David. permacultureprinciples.com

6. A few social permaculture resources: The Black Permaculture Network and Pandora Thomas’ work, People & Permaculture by Looby McNamara, Karryn Olson-Ramanujan’s “Pattern Language for Women,” The Permaculture City by Toby Hemenway, The Empowerment Manual: A Guide for Collaborative Groups by Starhawk, Adam Brock’s work with Invisible Structures (www.peoplepattern.org), Food Not Lawns: How to Turn Your Yard Into a Garden and Your Neighborhood Into a Community by H.C. Flores.

7. See the book catalogue insert included in the magazine for great resources.

8. See “David Holmgren on Permaculture: An Interview,” The Permaculture Podcast with Scott Mann, www.thepermaculturepodcast.com. April 4, 2013.

BIO

Diana Sette is a Certified Permaculture Teacher and Designer working primarily in Cleveland, OH, after almost a decade of growing in the Green Mountains of Vermont. She serves on the Board of The Hummingbird Project (hummingbirdproject.org) and GreenTriangle (greentriangle.org), two permaculture-based non-profits working locally and abroad. Much of her work in social and urban permaculture experimentation is centered at Possibilitarian Urban Regenerative Community Homestead (PURCH) in Cleveland (Facebook: Possibilitarian Garden). Diana currently works for Cleveland Botanical Garden as the Youth Manager of Green Corps, its twenty-year old urban agriculture work-study program for inner city teens.

Daniel and Rosemary checking out an aquaponic system in action at Seedfolk City Farm (

Daniel and Rosemary checking out an aquaponic system in action at Seedfolk City Farm (