by Elsa Johnson

British Naturalist Richard Mabey’s book, A Cabaret of Plants, is not a book to which one can do justice in a mere few hundred words, nor can one truly do justice to the reading of it while drifting in and out of a haze of pain meds (recent hip replacement), hence, this essay – which is not so much a meditation as a meandering.

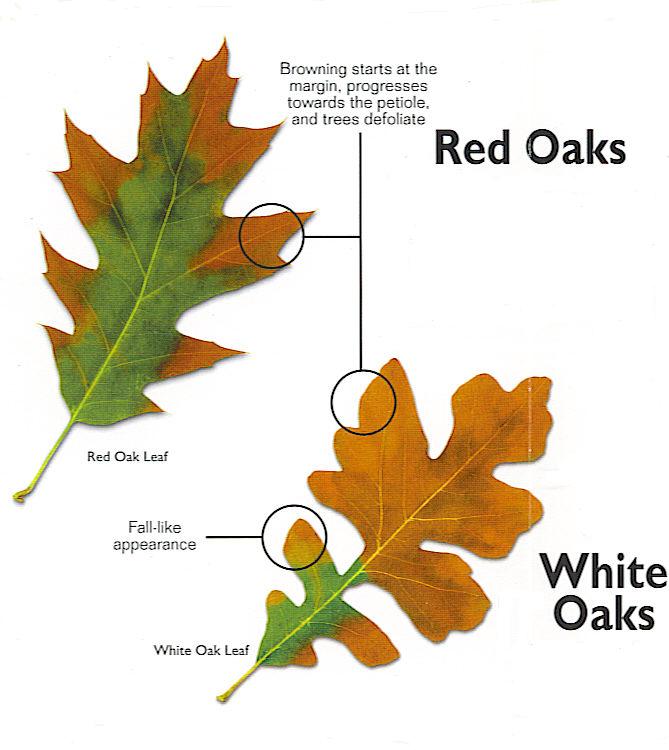

Here in Cleveland, Ohio, in the heart of the Eastern Broadleaf Forest, we have tended to take the abundance and diversity of our hardwood vegetation for granted – until we are reminded by loss or impending loss that, though seeming more durable than people, trees are vulnerable, too. Thinking that they are enduring, we are dismayed when they are stricken by disease. But we soon forget them. We do not even remember our native chestnut trees (chestnut blight); the American elm — anyone? (Dutch elm disease). Our memory of these once iconic trees grows limited — and it is a fact that we must remember, in order to value what we have lost. More recently: ash (ash borer); oak (oak wilt); white pine (blister rust); hemlock (wooly adelgid ). Who knows what is coming next to a tree near you. So, perhaps, it is time to consider the larger picture of what trees mean to us – so much more than just an (important) ability to sequester carbon.

Mabey is excellent at this sort of thing, so I picked out a chapter — From Workhorse to Green Man: The Oak — and drifted in.

There are, Mabey tells us, 400 to 600 species of oak spread across the northern hemisphere – a plant family that is quirky, opportunistic, mutable – and useful. From the Neolithic era on, the oak has been a crucial raw material, often used for surfacing some of mankind’s earliest walkways, like the Sweet Track, that crossed the Somerset marshes in England. That wood, well preserved, has been dated back to 3806 BCE, when it was cut. In France, an oak tree in Allouville-Bellefosse, 1,000 years old, contains, within its hollow trunk, two chapels, built in 1669. They are still used for Mass twice a year. We learn that the roof of Westminster Hall – containing 600 tons of wood spanning seventy-five feet without a central support – is essentially a ‘super-tree’ through an arrangement of trunk and branching that ’would not work unless it copied the structure of its motherlode’. And we learn that Ely Cathedral, built at the end of the 12th century, and called the Ship of the Fens, has an interior that resembles a ‘carved simulacrum of a an oak forest’ … and that the carpenter there altered his design to use several trees that were not quite long enough to reach all the way up to the roof’s spectacular octagonal lantern (well worth googling to see). In England, as in nowhere else, it seems, the oak became emblematic of nationhood and character.

Mabey also tells us it is not by coincidence that that oaks and humans share habitat preference and are coterminous – oaks having been an important food source. Eventually, Mabey gets around to the Green Man — those foliate heads that are emblematic generative figures of mythic — possibly demonic — creativity, and which, oddly, often reside in churches but fit no formulaic interpretation. Mabey calls them ‘an irresistible eye-worm for stone carvers.’ In the Lady Chapel at Ely Cathedral, many of the carven images of Mary were smashed or decapitated during the Reformation (the ISIS of its day) – but the Green Men and the symbolically sinful foliage were puzzlingly intact.

Perhaps, Mabey suggests ‘ the exuberant carving seems a celebration of the unbroken connectivity of the living world’. So I leave you with that, and a poem , which also celebrates the organic vitality of the Green Man.