by Diana Sette

PERMACULTURE IS CONSTANTLY WORKING to model systems after designs in nature, and the practice of hugelkultur is a prime example. Before we get into talking about hugelkultur, I invite you to imagine the forest floor of an old growth forest. Layers of humus, maybe little slopes from tree roots, or moss-covered, decomposing fallen logs, cover the landscape. Herbaceous plants unfurl in the crevices and atop mounds. Self-mulched surfaces produce rich, organic matter from which mushrooms and shrubs spring. Decaying leaves are food for worms, insects, and other arthropods. There is no need for a hose to water, and if it down-pours there, it is unlikely to flood, as the carbon-rich soils have such an extensive water holding capacity. In addition to that, no human needs to fertilize the trees, or the ferns, or the herbs and shrubs producing beautiful berries and nutrient-dense greens. No, this system is self-sustaining and regenerative.

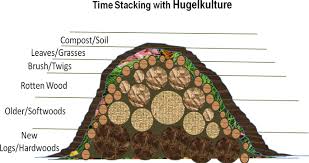

From this springs the inspiration for hugelkultur. Hugelkultur is a raised bed with an intentionally layered structure with large wooden logs as the base layer. Layers atop the thick fallen-tree-like-foundation include smaller logs, branches, twigs, manure or other high nitrogen organic waste, local soil with indigenous microbes, straw, compost, wood chips, grass clippings, and even food scraps. The idea is essentially to recreate the conditions of a forest floor by building a raised bed with a compost pile that balances the carbon (“browns” like wood and straw) with the nitrogen (“greens” like food scraps, manure, or grass clippings) all put into the raised bed.

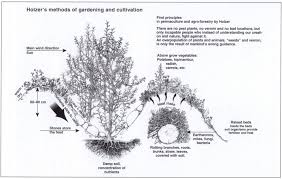

Sepp Holzer, a permaculturist from Austria, popularized the hugelkultur practice as a way to build a self-fertilizing garden with minimal irrigation and increased growing space and microclimates. Many people across the planet are beginning to implement this practice in their garden-farms. Why? For lots of good reasons!

First, once you start working with trees and perennials, any gardener can tell you that it’s not hard to accumulate a large pile of cuttings from pruning, or from rotten wood. Therefore, hugelkultur is a practice that supports putting those waste products to good use by recycling their nutrients.

Second, hugelkultur is a great way to build soil. As mentioned above, the layering process, similar to “lasagna gardening” but with wood and logs included, is like building an instant compost pile in your raised bed. Also, if you’re gardening in an area with compact clay soils or water-logged areas, hugelkultur beds can be the solution to building soil through raised beds.

Third, to reiterate the point above, hugelkultur beds are self-fertilizing because they are built to be like slow-release compost piles that feed the microbial life in the soil, giving access to nutrients and minerals in the earth.

Fourth, hugelkultur beds require minimal irrigation. Woody material has a great capacity to store water—by imitating the forest floor and building a raised bed with dead woody material as the base, you are creating a growing bed that can hold water in its structure. The wood retains moisture and feeds it slowly to plants as needed.

Fifth, the practice of hugelkultur supports the conservation of water and also increases drought-tolerance.

Sixth, like any raised bed, the mound structure of hugelkultur provides a height advantage that is more resilient to floods. In addition to simple mounding, the log layers will work to absorb excess water and spread it upward, while the height will keep many plants growing at a higher level high and dry.

Finally, hugelkultur expands the “edge” and microclimates available to grow in. Think of the ever-popular herb spiral that capitalizes on the variation of height and growing conditions in a contained spiral pattern. The plants at the top enjoy slightly warmer and dryer soils, while the plants toward the base of the spiral enjoy damper and cooler soils. The same scenario plays out for the hugelkultur bed that is more angled.

While many hugelkultur beds are built to be a more rounded, half-circle type shape, others can be taller or triangular to better leverage the potential for diverse growing conditions or microclimates. The extra steepness of the tall triangular shape also allows for the natural settling of decomposition. Some hugelkultur builders have utilized wooden pallets as a base for the sides of the hugelkultur bed to help support the structure of the steepness, while also providing a little more foundation for planting at various heights. People who build hugelkultur beds more tall and steeply also report the benefit of an easier harvest due to less bending and reaching. Clearly, the reasons to build a hugelkultur bed are extensive!

How to build a hugelkultur bed

Materials needed:

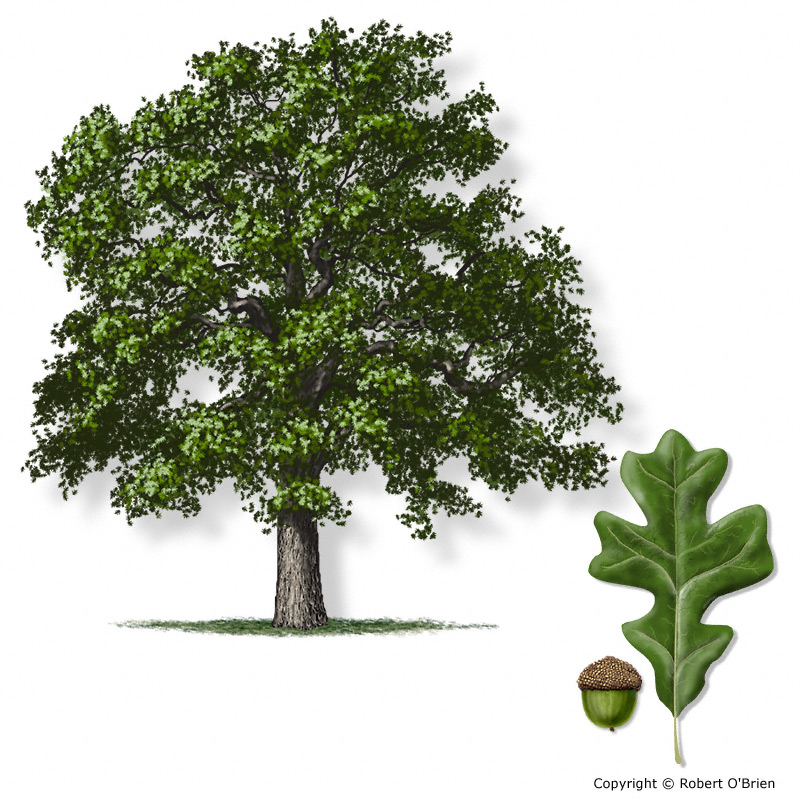

• large logs or tree trunks (best if soaked overnight or for a few hours beforehand). The type of wood you use for the beds is important. Softwoods like apple, alder, poplar, dry willow, and birch are generally best—similar choices as you might make for growing mushrooms. Avoid eucalyptus, cedar, or cypress because of their acidity and/or anti-fungal, anti-microbial properties.

• water • medium-sized trunks & branches

• shovel

• spade

• wheelbarrow

• ground stakes, rope, or spray paint (optional, but helpful)

• small branches (not necessary, but useful)

• recently pruned green material

• organic waste/manure/food scrapes

• local soil

• compost

• straw

• wood chips (optional)

Step 1: Decide on the location of the bed.

Step 2: Use the ground stakes/rope/ spray paint to outline the bed. This step is especially useful, and highly recommended when working with a larger group, so that everyone understands and can easily visualize the plan.

Step 3: Use spades and shovels to edge the outline, and then dig a 3-4” trench. Important: save the soil for later.

Step 4: Place the large logs as the bottom layer of the trench. This will help to improve drainage and retain humidity of the bed soil. It is preferable that the logs are pre-soaked prior to using, as this will significantly help the soil and microbes get off to a good start in maintaining moisture for the bed. If logs are not pre-soaked, another option is to run the hose during the process of layering the bed as to wet all materials.

Step 5: Place smaller tree trunks and branches on top of the bigger ones.

Step 6: Place organic waste, or recently pruned green material on top of that. This nitrogen layers will balance the slow-to-break-down high-carbon layers of wood.

Step 7: Place the soil from Step 3 on top of the pile. This will seed indigenous microbes into the bed.

Step 8: Cover with compost to give soil health a jumpstart.

Step 9: Top off with either straw or wood chips, and plant within the top layer of the bed. Plants that need less water should be planted towards the top of the mound, and those that need a larger amount of water should be planted near the bottom.

Many hugelkultur gardeners recommend waiting a full moon cycle before planting the bed to allow for settling and integration of the layers. The devil’s in the details… A few notes to consider when building a hugelkultur bed: Have all materials prepared and ready on-site before starting. Building a hugelkultur bed can be hard work with the lugging of large logs and piles of soil and wood chips. It’s always a good idea to get a group together to help. Maybe offer it as a free skill-share event about hugelkultur beds, or be ready to offer the nutrient-dense food that will be growing soon. However you do it—remember, many hands make light work! Save annual prunings for hugelkultur layering materials. If you want an added bonus of mycelium, when soaking wood materials in water, you can use mycelium powders mixed into the water as an inoculant to jumpstart the soil food web for the new raised bed. For the top of the hugelkultur mound, select plants that need less water like garlic, and for the bottom, chose plants that enjoy more water like beans.

If one does want to use irrigation for the hugelkultur bed (e.g., in drylands or during extreme drought), there are a couple options to consider. One option is to shape the hugelkultur bed in a more tiered fashion, allowing for lines of drip irrigation to be laid down and staked along the top ridge, then along two tiered levels on the sides of the bed, and two more along each side at the base. Using drip irrigation is the most water-saving approach.

However, another option for irrigation that is perhaps more efficient in utilizing the benefits of how the moisture flows through the hugelkultur bed, is implementing irrigation channels. This method of irrigation is particularly useful if your growing area is prone to flooding. Have fun and happy hugelkultur!

∆ Diana Sette is a passionate community cultivator, gardener, writer, facilitator, and mother. She is a Certified Permaculture Teacher and Designer, and is the Co-Founder of Possibilitarian Garden (Facebook: Possibilitarian Garden) and Possibilitarian Regenerative Community Homestead aka PORCH (www. buckeyeporch.org) in Cleveland, OH. Diana serves on the board of The Hummingbird Project (hummingbirdproject.org), and Green Triangle (greentriangle.org). She is a frequent contributor to Gardenopolis Cleveland. More on Diana at dianasette.wordpress.com.