by Mark Gilson

People often ask why Lake County became such a mega-center for nurseries.

In the beginning, 1854, the first nursery resulted from the vision of one man, Jesse Storrs, who moved his family and nursery to Painesville from Cortland, New York. Four years later, he was joined by another visionary, JJ Harrison, an English immigrant, and they became partners in what would become the largest departmental nursery in the world. Transportation undoubtedly played a role in attracting Storrs to Northeastern Ohio. The railroads arrived in 1852 and connected local farmers, finally, to eastern markets. But there had to be more than transportation attracting these horticultural pioneers and the additional 200 nurseries that followed.

In the beginning, 1854, the first nursery resulted from the vision of one man, Jesse Storrs, who moved his family and nursery to Painesville from Cortland, New York. Four years later, he was joined by another visionary, JJ Harrison, an English immigrant, and they became partners in what would become the largest departmental nursery in the world. Transportation undoubtedly played a role in attracting Storrs to Northeastern Ohio. The railroads arrived in 1852 and connected local farmers, finally, to eastern markets. But there had to be more than transportation attracting these horticultural pioneers and the additional 200 nurseries that followed.

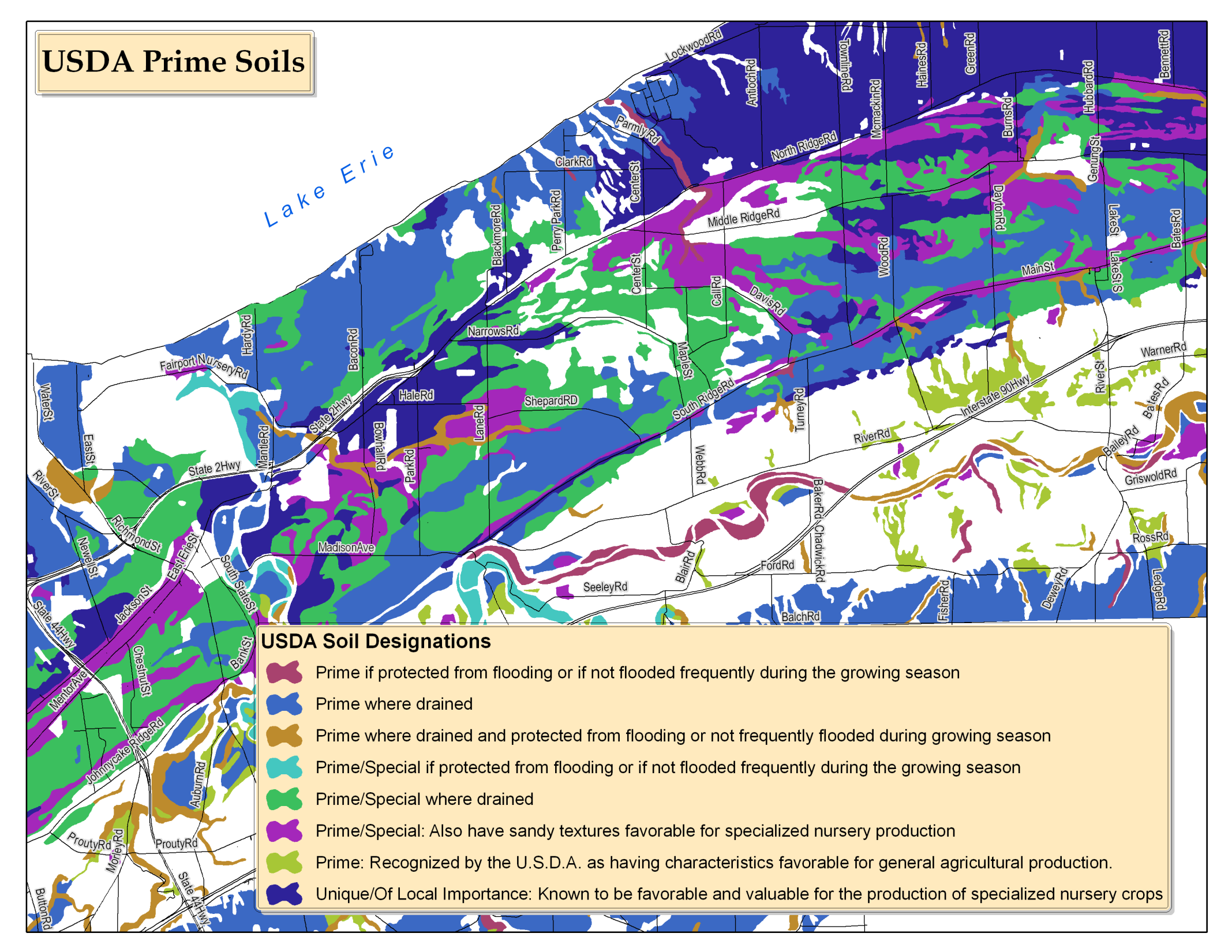

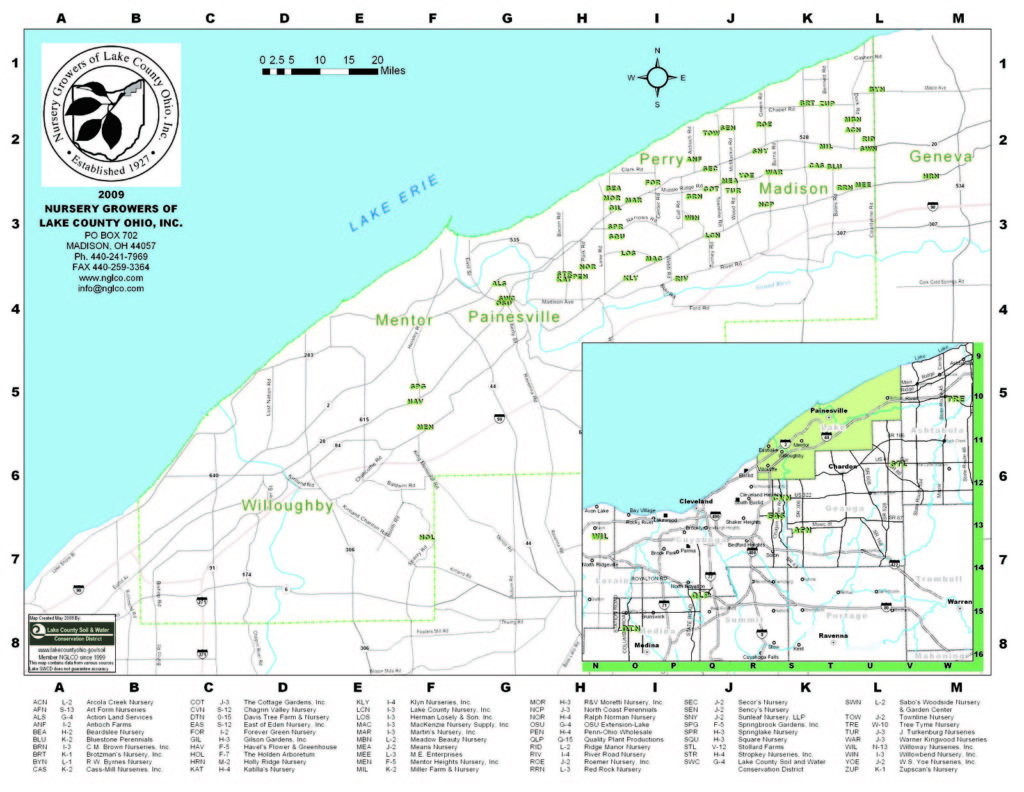

A study of the nursery locations in eastern Lake County reveals a ‘Nursery Belt’, three to seven miles from north to south beginning near the Lake Erie shoreline, and twenty miles wide, extending from County Line Road in Madison (a few historic nurseries were located to the east in Ashtabula County) and then westward through Mentor.

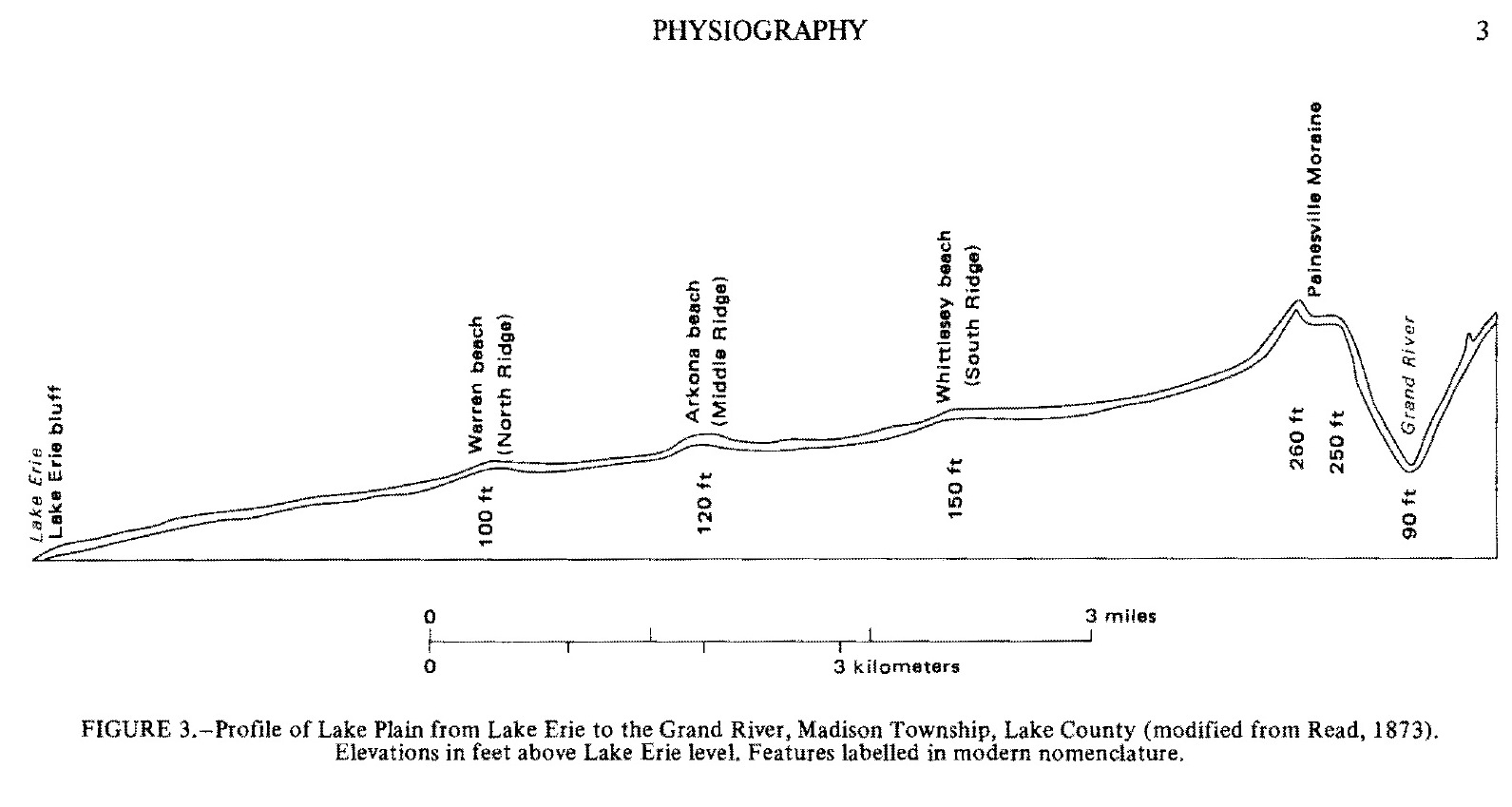

To understand this Nursery Belt we need to look back over our geological history to the glaciers and the formation of three ancient lakes…four if we include present-day Lake Erie…from which we derive such gentle topography and such a diversity of unique productive soils.

During the most recent ‘ice age’ (known as the Wisconsin period extending from 11,000 to 100,000 years ago) Lake County was covered at least five times by glaciers, sometimes up to a mile high. Some glaciers extended well into Southern Ohio but the most recent reached only into southern Lake County. With each glacier came sand, gravel and rocks from the north. With each thawing and retreat, lakes were formed. The beaches from three of those ancient lakes gave rise to the ridges we recognize now.

Whittlesey was the highest ancient lake, 150’above current-day Lake Erie. Deposits of sand and gravel up to 20’ thick follow its irregular path from Unionville, through Madison, Perry, Painesville, and westward through Willoughby, conforming to a great extent with the current South Ridge Road (Rt 84). This ancient beach defines the southern edge of the Nursery Belt since soils beyond it generally become heavier and less hospitable. The nurseries of Wick Hathaway (1877) and Ed Wetzel (1917) were founded on South Ridge Road in Madison. Wetzel, like many others, began as a childhood worker at Storrs & Harrison Nursery at age 11. Gerard K Klyn Nursery began in 1921 on Center Street in Mentor, across from the current Mentor High School, but moved to Rt 84 in Perry in 1966. LCN began as Zampini Nursery and Champions Nursery in Perry Village but relocated to South Ridge Road in the 1980s on the site of the former Nick Mesman Nursery. These two operations continue to dominate the high ridge above the Nursery Belt.

Soils throughout the Nursery Belt were formed from glacial till then shaped and reshaped by waves and wind. Some contain abundant organic matter like the strip of black muck that runs just to the north of North Ridge. Some are more sandy, especially as they near the current lakeshore. Some have higher concentrations of clay rendering them ‘heavier’ like those in Mentor favored by the Rose Growers. The true story is this: Lake County is not just blessed with ‘good soil’…but with a unique diversity of fertile soils. A review of the soil map for the Nursery Belt reveals over 17 discrete types.

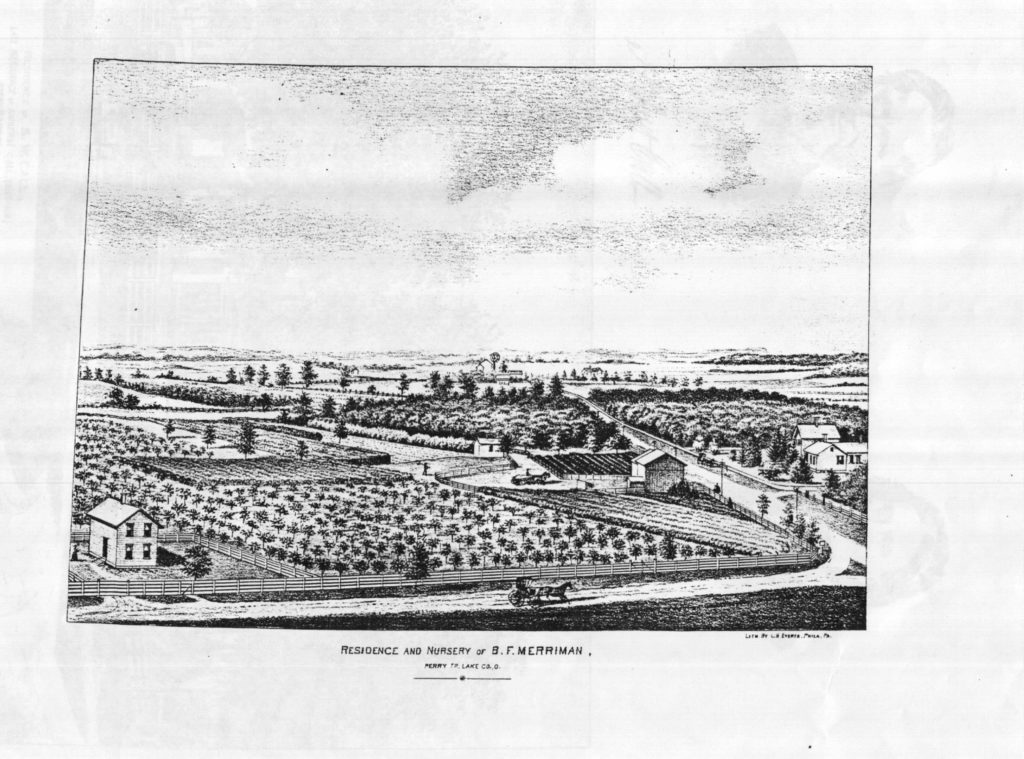

At 120’ above Lake Erie, the ancient shore of Lake Arkona defines the Middle Ridge, which follows a discontinuous line along ‘Middle Ridge Road’ in Madison and Perry, following ‘Narrows Road’ as it nears Painesville and joining with Johnnycake Ridge Road in Mentor. Early nurseries founded in Perry near ‘Middle Ridge’ included L. Green & Son (1865), Merriman Nursery (1868), Call’s Nursery (1874) Champions (1891), TB West Nursery (1893) which later became Champions, and Dugan Nurseries (1908). More recent nurseries include Maple Bend, Frank Square’s Nursery, Cottage Gardens, Don Stallard’s Nursery and CM Browns(1970) in Perry; Crawfords, Turkenburg , Cass-Mill and Bluestone(1972) in Madison.

North Ridge, closest to modern Lake Erie and rising 100’ above it, conforms to Lake Warren as it winds, splits and reforms along North Ridge Road (Route 20), becoming Erie Street, Mentor Avenue and Euclid Avenue on its way to downtown Cleveland. Many still remember the Rt 20 of the 1950s prior to the interstate highway system. Trucks and cars lumbered by at all hours on their way from Buffalo to Chicago. Numerous small motels with guest cabins operated in every community along the way.

Interspersed in the traffic were tractors, farm wagons and stake-trucks, driven by Italians, Puerto Ricans, Hungarians and every other nationality as they attended to the daily demands and realities of The Nursery Capital of the World.

Well-drained soils on beach ridges and terraces throughout the area include Chenango, Chili, Conotton, Oshtemo, Otisville and Tyner, although the last four do not hold together well for digging, balling and burlapping. Poorly drained soils such as Fitchville, Stafford, Painesville and Red Hook offer better digging qualities once the fields are tiled and drained. Some areas such as Perry were originally covered with wetlands. ‘Elnora loamy fine sand’ to the north of Rt 20 in Perry is a productive nursery soil when artificially drained with tiles. The ‘Elnora’ soil is often interspersed with fast-drying ‘Colonie loamy fine sand.’ To the south of North Ridge Road local growers in Perry encounter ‘Tyner loamy sand’ on the post-glacial beach ridges. These soils are accessible to tractors and equipment early in the season but require irrigation for summer crops.

Productive ‘topsoils’ range from three to eighteen inches deep. Since topsoil can require 500 to 1000 years per inch to occur naturally, depletion of the surface levels over time is a serious concern. Fortunately, digging and shipping of balled and burlapped nursery stock depletes the topsoil very slowly over many decades. In addition, modern nurseries specializing in field-grown material employ aggressive soil re-building techniques, such as cover cropping and the introduction of fresh organic matter each season in the form of nursery compost, leaf compost from local residential neighborhoods and specially formulated ‘county compost’ from local sewage treatment plants. These materials are cultivated into the subsoil each year and provide a sustainable model for future nursery production.

Read Part 2 next week!

Sources:

- White, George W., Glacial Geology of Lake County, Ohio, State of Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Geological Survey, Columbus, 1980.

- Ritchie, A. and Reeder, N.E., Soil Survey of Lake County, Ohio, United States Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service, January 1979.

- Edgar, Chad, Lake County Soil and Water Conservation District, April 2018, conversation with Mark Gilson.

- George ‘Josh’ Haskell, local attorney and historian.

- Bob Endebrock, Ohio Department of Agriculture Nursery Inspector (retired)

- James Schroeder, Mentor Rose Growers.

- Perry Historical Society.

- Morley Library.

- Thanks to various additional sources associated with Nursery Growers of Lake County Ohio, Inc.

- Photos courtesy of Perry Historical Society, NGLCO File and Mark Gilson.

Mark Gilson is a third-generation nurseryman and past-president of Nursery Growers of Lake County, Ohio. Visit: http://gilsongardens.biz/category/marks-corner/

Mark Gilson is a third-generation nurseryman and past-president of Nursery Growers of Lake County, Ohio. Visit: http://gilsongardens.biz/category/marks-corner/