text by Elsa Johnson, photos by Ann McCulloh

A brief summary follows of the talk by the keynote speaker at the 2019 pollinator symposium — Larry Weaner: Breaking the Rules / Ecological Landscape for Small Scale Residential Properties.

The biggest take-away from Larry Weaner’s talk for this Gardenopolis writer/editor was the difference, as he saw it, between traditional landscape design – which he described as seeing the garden as separate plants in ‘designs’ — and a contemporary response of seeing the landscape as an ecology, as an evolving restoration. That traditional garden scale, says Weaner, doesn’t work, and, indeed, many of his examples were of large scale projects, though the process is workable at any scale, as one picture of his own backyard patio showed.

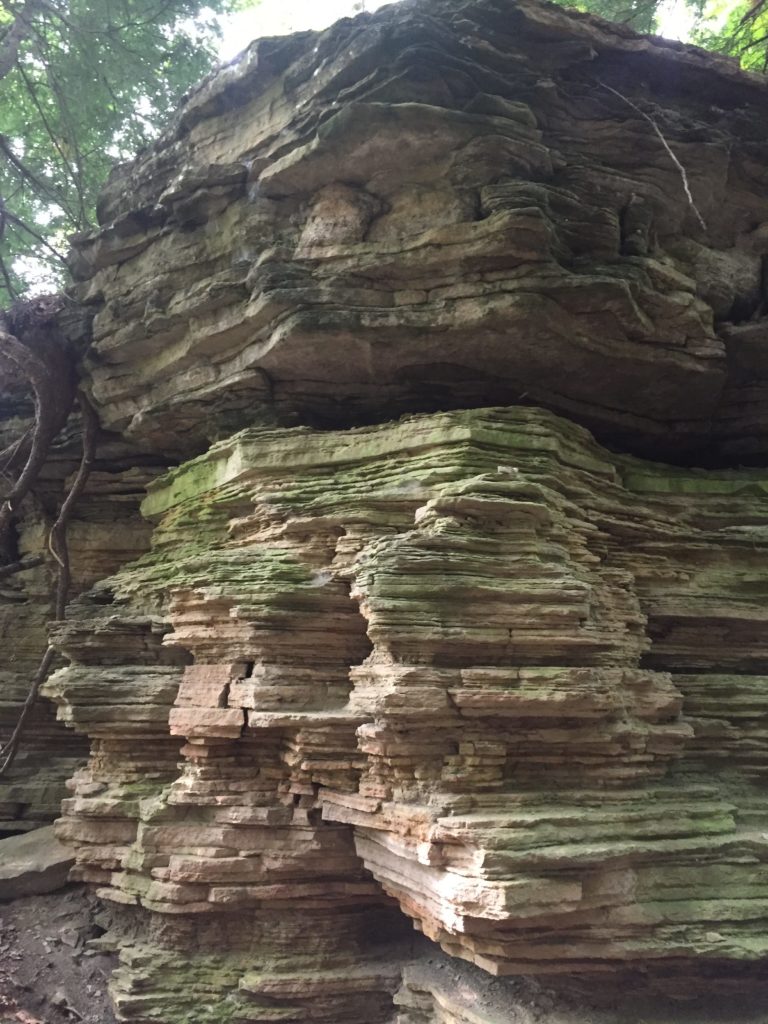

What is meant by seeing a landscape as an ecology? Such an approach begins with native flora because one needs native flora (supplying food, water, cover) to attract native fauna – no; not talking about our backyard deer. Rather, he gave the example of putting a stick over water to draw in dragonflies, an example that begins to bring an awareness of nature’s micro-scale natural complexity and inter-connectedness. Within this context, however, he stipulates that the client’s level of comfort – he calls it ‘happiness’—with this concept, dictates how far to push. It is a different kind of order, one that by its very nature changes over time.

This is a key point: Natural compositions do not remain stable over time.

An aside here – what garden designer/artist/architect does not have a client or clients who expect their landscape to remain static, like a living room that’s been decorated and expected to forever remain just-so?

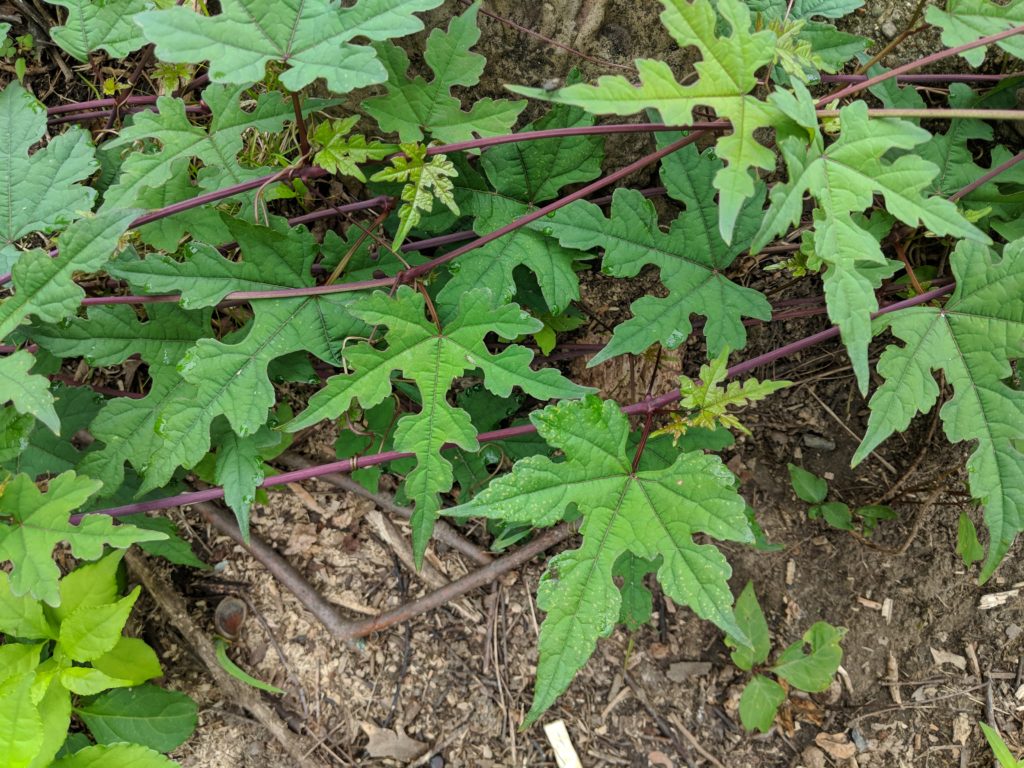

Forget ‘proper spacing’, said Weaner. Forgo mulch – which has no value at all for animals — in favor of suppressing weeds with dense planting. Allow natural succession. Plants go – if you allow them – where they want to grow. Knowing this one can use targeted disturbance to achieve design by removal. Notice where and how each plant grows. There is a learning curve: one plant teaches you about many. Species can be planted as seed sources that will find their own places to grow – and not necessarily where you planted them. Weaner stresses habitat fidelity over imposed design – use plants that have traditionally grown together.

Become aware of micro habitats in site design. There are plants that Weaner calls ‘generalists’, and then there are ‘specialists.’ Knowing the levels of disturbance, for example, offers opportunity to use plants like cardinal flower whose seeds will migrate to disturbed areas. This is ‘design’ that allows the landscape to be a series of evolving compositions, multi-layered evolving composition, over time.

Go ahead. Break the rules.

After lunch I attended a breakout session lead by John Barber, who spoke on planting native plants for birds. Want birds? Here’s what to do: provide clean and safe water; plant native trees and shrubs; never use insecticides (95% of birds feed their chicks insects) or rodenticides (hawks eat rodents — you end up killing the hawk also); and never ever let your cats outside.

Further, bird feeders, says Barber, have no real positive impact on birds, and winter survival is not actually improved by winter feeding. Additionally, the foods you are providing may have a large carbon footprints. Feeders also may concentrate birds unnaturally, making it easier to spread diseases. Additionally, feeders bring blue jays and grackles. Both are baby bird predators of cup nests birds.

Instead of bird feeders, plant native plants. They have co-evolved with native birds, are adapted to the environment, are more nutritious, and, once established, require less maintenance. Birds have highest nesting success when at least 70% of the plants in a landscape are native. In the fall avoid the nursery and landscape maintenance model of landscape care—i.e., early fall cleanup. Leave plants up longer; leave some litter, logs, and bare earth.

Barber recommends the book Planting Natives to Attract Birds to Your Yard, by Sharon Sorenson.

And finally, did you know that Virginia creeper won’t make berries unless it climbs? — Neither did I.

The last speaker I heard was Susan Carpenter, Senior Outreach Specialist at the Wisconsin Native Plant Garden, who spoke on creating and maintaining Pollinator habitat. This was a dense fast talk and I was not able to get much of it down on paper. She said, however, that it is all accessible on line at https://go.wisc.edu//pg8340.

Sorry not to report on Przemek Walczak’s talk Restoring Bell’s Woodland, or Sam Droege’s talk Native Bees: Protecting our Urban Pollinators. I was obliged to miss these.