by Toni Stahl, Habitat Ambassador Volunteer, Backyard Habitat

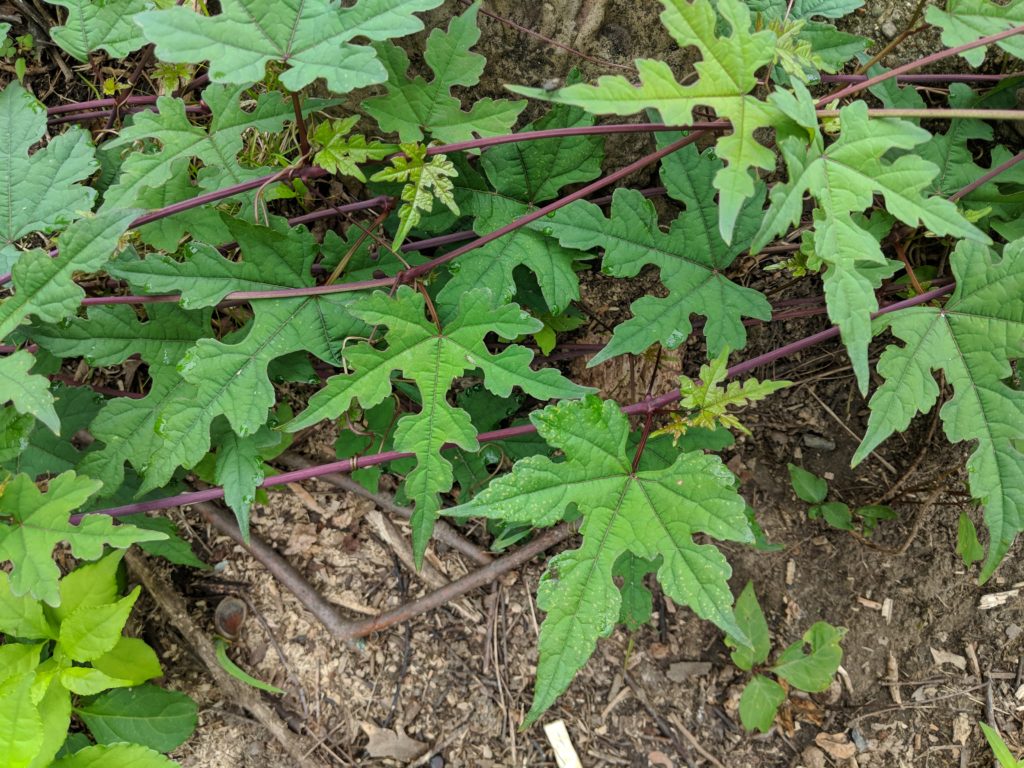

Hummingbirds are a pollinator. There are a few plants that only they can pollinate, such as Cardinal Flower (photo from my yard above) and Royal Catchfly. We can save hummingbirds with more than sugar water. During the summer, hummingbirds nectar from my plants and rarely use the feeder. They are a woodland bird, so plant native trees for cover and places to raise young. Plant chemical-free, tubular shaped nectar plants for food. Here is a list what I’ve provided in my Ohio yard to save hummingbirds.

Adding native plants to your yard doesn’t need to be weedy. You can landscape them just like you would non-native plants. I was interviewed in the recently updated Ohio Animal Companion articles about going native and how to create a functioning wildlife habitat. Ask native plant vendors to help you with your selection so you can put the right plant in the right place. A link for the Ohio list is in the going native article, but for other state lists, click here.

We can save bees in our yards. They work hard for us by providing 1 out of every 3 bites of our food, so please don’t swat at them. Don’t confuse bees with wasps, hornets or yellow-jackets that sting to protect their nests. Carpenter bees fly beside me and buzz loudly, but they are harmless. If carpenter bees drill holes into your wood that cause problems, paint the wood with polyurethane in early spring right after the bees have emerged. Provide clean water in a shallow dish with rocks, plant the Cup Plant, which holds dew, or make mud or sand puddles. Buy plants from a reputable organic native plant dealer to ensure that the plants don’t contain pesticides that kill bees. Plant a variety of native plants that bloom at different times throughout the season. For a bee plant list, enter your zip code to see your Pollinator-Friendly Plant Guide.

Good news: National Wildlife Federation honors America’s Top Ten Cities for Wildlife. Cincinnati, Ohio is a new one on the list. Be inspired.

Tips for Your Yard

- Organic Lawn Care: Apply Corn Gluten when the soil reaches 50 degrees (between 3/15 and 4/10 in central Ohio, when crocus blooms) as a pre-emergent broadleaf weed control

- 5 weeks after using Corn Gluten (if we’ve had enough rain), over-seed weedy or bare areas with a pesticide-chemical-free grass seed, like TLC Titan, available at most home and garden centers; keep seed damp until grass is 2″ high

- Pull out weeds or spot-treat weeds sparingly with an organic product, only if necessary, such as Iron (a few brands are Whitney Farms Lawn Weed Killer Iron, Fiesta or Garden’s Alive Iron X)

- Mow high to shade out weeds (3″-4″)

- Bluebird houses: Transparent fishing line (monofilament) deters house sparrows from killing bluebirds and other cavity nesting birds in their bird houses, except that 20-lb is recommended instead of 6-lb weight

- Birds love moving water, but it’s easy to trip or mow over the tiny hose for a dripper. Using a shovel, create a slit in the lawn about 3-5″ deep and 1″ wide by rocking the shovel back and forth. Push the tiny hose down and close the soil over it to make the soil flat and protect the hose for the season. The hose will be easier to remove when the ground starts to freeze than if you buried it

- Plant native milkweed for Monarch butterflies

- Leave plant materials in place throughout winter and into the nesting season to supply bird nesting materials naturally. Here are ideas for extra bird-nesting materials

- When an invasive Garlic Mustard plant is in its second-year, the flowering stage, gently dig out the entire root of the plant. If you can ID the first-year rosette, gently pull it out. Important: Bag the flowering stage plant and put the bag in the trash (not in compost or yard waste) because the plant continues to go to seed even after removed from the ground

- In spring, invasive bushes become green before most native plants, so they’re easy to see. Cut the invasive plant at or near ground level and cover with cardboard. If it is pesky, cover with black plastic

- To keep an Invasive Plant away, put an alternative native plant (if a bush: a bush; if a flower: a flower) in its place

- Cut flower stalks to 12-15″ and leave them standing until summer (late May to early June in the Midwest) after the small carpenter bees that used them for nests have emerged

- Put out hummingbird feeders April 15 to Oct 15 in mid-Ohio to help Ruby-throated hummingbird migrants and summer residents. Watch this migration map for timing in other areas

- Contact your Public Health Department to find out if your city does mosquito fogging and, if so, ask how to opt out. These chemicals kill beneficial insects, including bees and Monarch caterpillars

- Help migratory birds by turning your outdoor lights off or down 11:30pm-5am from mid-March to mid-June to keep birds from being disoriented and having nighttime collisions

- Apply organic tree fertilizer to the root zone to help trees make leaves

- Best bets on what to plant by zip code from Doug Tallamy and National Wildlife Federation

- When you have your chimney cleaned in early spring, close the damper, uncap it and add a cover 12″ above chimney with openings on the sides so that a pair of Chimney Swifts can use it for their summer home and nest for babies. See tips here

- If you find unattended baby or injured wildlife in your yard, here’s what to do from the Ohio Wildlife Center Hospital

Nature News

- 30,000 Trees Planted Last Summer for Eastern Monarch Overwintering Sites

- Eastern and Western Monarch’s Spring and Fall Migration Paths

- Reg now for 5/3-5/12, Biggest Week in American Birding, Fee, National warbler event, Bird watch even if you can’t attend workshops, Ohio

- TJ’s Top 10 Natural Bird Feeders

- Planning a Natural Habitat

- Create a Hedgerow

- How to Save Nature, One Backyard at a Time

- Native Shrubs and Why They’re Essential for Carbon Sequestration

- Organic Practices

- The Wildlife Friendly Yard: An Introduction

Ohio Habitat Ambassador Nature Events

- 4/13, Plant This, Not That: Native Alternatives for Invasive Plants, Garden for Wildlife Exhibit, Wild Ones Columbus, Delaware

- Reg now for 4/20, Herb Gardening: Good for You, Good for Wildlife, incl. Garden for Wildlife Presentation, Fee, Cincinnati Nature Center, Milford

- 4/27, Native Perennial Plant Swap, Garden for Wildlife Exhibit, Tecumseh Land Trust, Yellow Springs

- Reg now for 4/28, Conversations on Conservation: Basic Bugs 101 with the Bug Chicks, Garden for Wildlife Exhibit, Fee for non-members, Cincinnati Nature Center, Milford

Other Ohio Nature Events

- 4/9, Climate Change: Causes, Consequences and Call to Action, Wild Ones Oak Openings Region, Sylvania

- 4/13, Native Plant Sale, Aullwood Audubon, Dayton

- 4/19-6/2, Native Plant Sale at the Nature Shop, non-members entrance fee Cincinnati Nature Center, Milford

- 4/23, Audubon’s Bird Conservation in the Great Lakes, Columbus Audubon, Columbus

- 4/28, 2019 Annual Plant Walk, Friends of the Ravines, Westerville