Lobelia cardinalis

The cardinal flower, a water-loving perennial, produces brilliant stalks of bright red blooms beginning in mid-summer. Its affinity for water makes this flower an excellent choice for rain gardens, swales, ditches and pond edges.

Lobelia cardinalis

The cardinal flower, a water-loving perennial, produces brilliant stalks of bright red blooms beginning in mid-summer. Its affinity for water makes this flower an excellent choice for rain gardens, swales, ditches and pond edges.

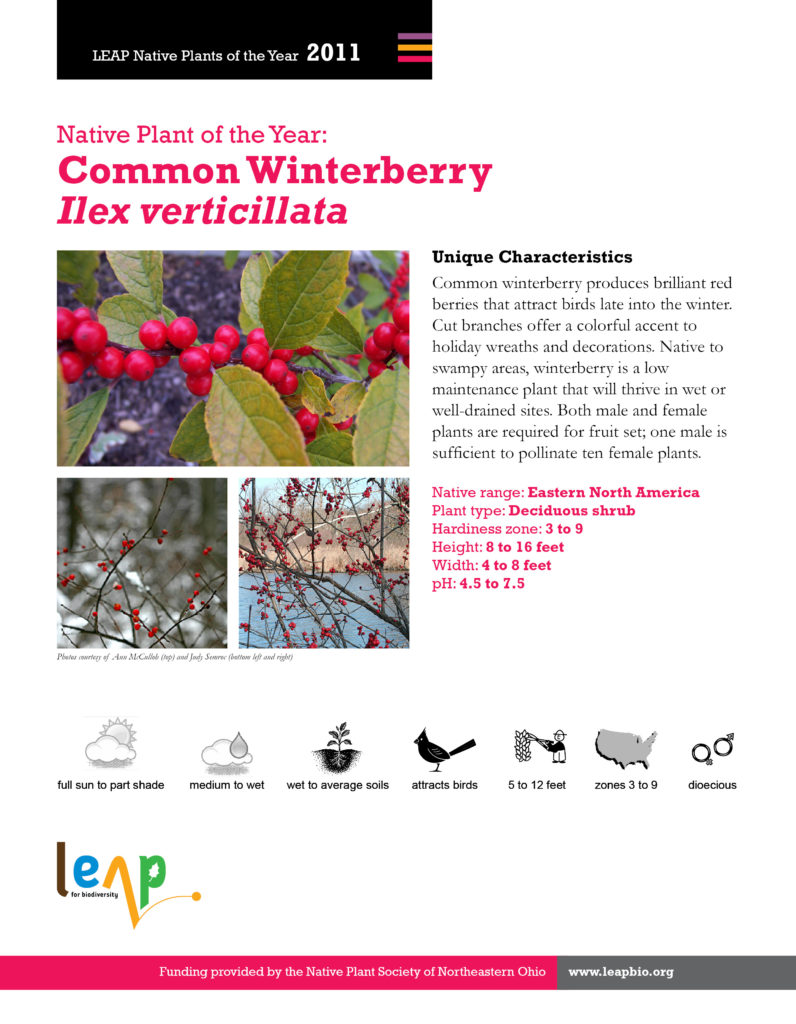

Ilex verticillate

Common winterberry produces brilliant red berries that attract birds late into the winter. Cut branches offer a colorful accent to holiday wreaths and decorations. Native to swampy areas, winterberry is a low maintenance plant that will thrive in wet or well-drained sites. Both male and female plants are required for fruit set; one male is sufficient to pollinate ten female plants.

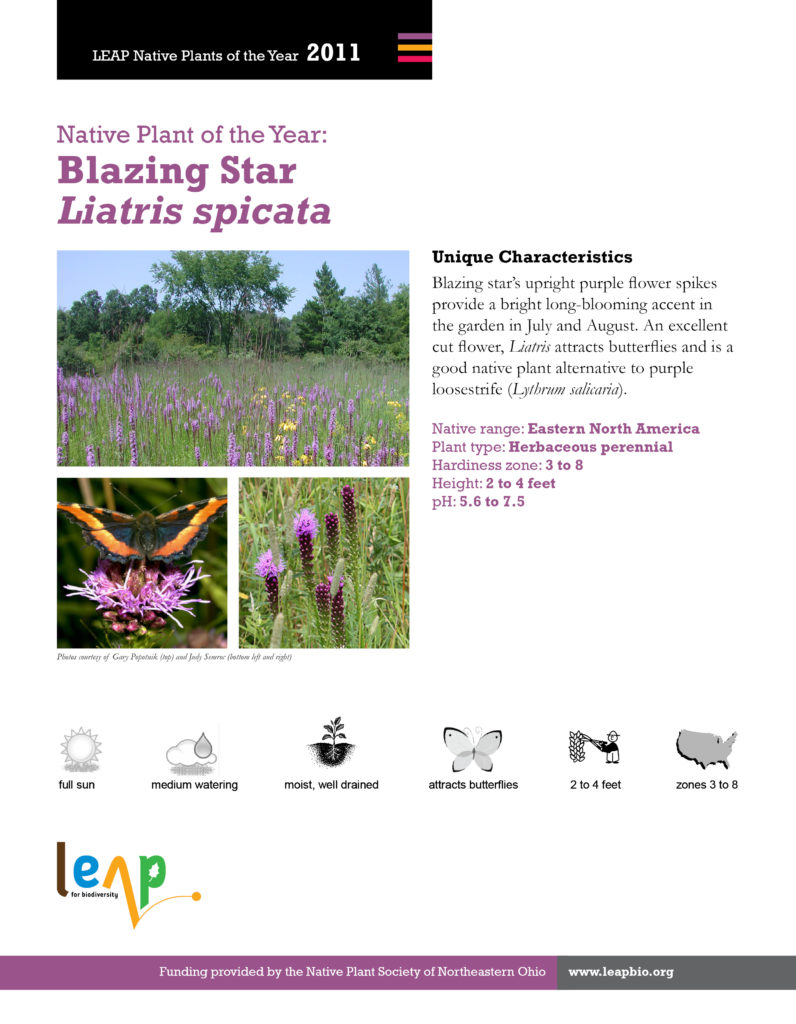

Liatris spicata

Blazing star’s upright purple flower spikes provide a bright long-blooming accent in the garden in July and August. An excellent cut flower, Liatris attracts butterflies and is a good native plant alternative to purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

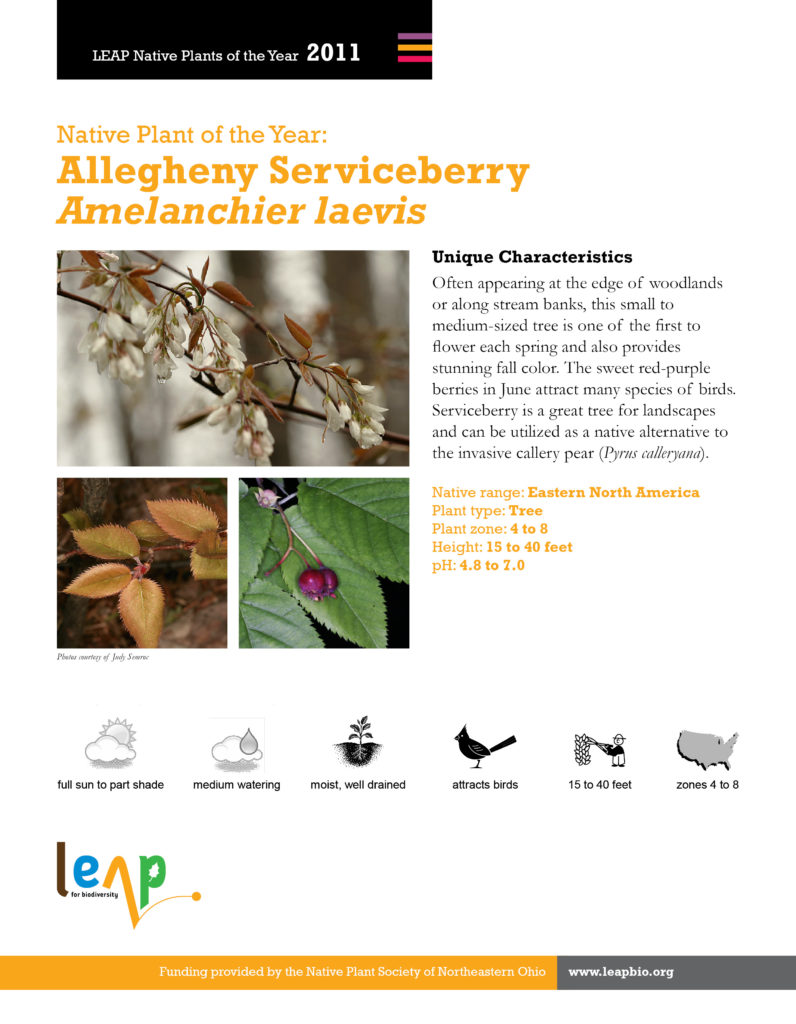

Amelanchier laevis

Often appearing at the edge of woodlands or along stream banks, this small to medium-sized tree is one of the first to flower each spring and also provides stunning fall color. The sweet red-purple berries in June attract many species of birds. Serviceberry is a great tree for landscapes and can be utilized as a native alternative to the invasive calley pear (Pyrus calleryana).

In recognition of April as Ohio Native Plant Month, members and partners of the Lake Erie Allegheny Partnership (LEAP) will celebrate one native plant a day. Over the past 10 years the LEAP Native Plant of the Year campaign has highlighted native species that can make exceptional additions to area landscapes and gardens while reducing the threat of invasive non-native species to the region’s biodiversity. Please visit the LEAP website and join us in celebrating Ohio Native Plant Month.

by Elsa Johnson and John Cross

What were the highest and lowest temperatures on your trip?

Highest was in July in New York — around Great Barrington, I think was the town. It got up into the nineties, approaching one hundred. It was high enough that the Conservancy sent out notices to all hikers to stay inside for the next few days. Hikers were have heat stroke. It was a hard section to have that happen. It was right when a lot of hikers and myself were facing sticker shock, because once you got to New York, all the hotel prices skyrocketed. That was one of the times when I had to spend the night at a hotel. I was exhausted. I needed to rest, and it was two hundred dollars a night, and it wasn’t even that nice a hotel — on top of the fact that so many hikers were trying to get off the trail that all the hotels were taken. The heat affected me, but I was able to manage through it. Some hikers, it bore down on them and slowed them down dramatically.

And the lowest temperature?

That was at the beginning of the trail, and the end of the trail. The beginning was the coldest day, when I was hiking with my friend. We were going up into the Smokey Mountains. Fontana Dam is there. It’s a cool spot because it’s the tallest dam east of the Rockies. We were in a kind of limbo because there were a lot of storms moving through. We thought — we’ll have one bad day and then it will be pretty clear. You do have to be careful because you’re going so high up, if you have any thunderstorms, you can get into a precarious situation. A lot of hikers did, but we lucked out with our timing. This was our first day, as we were going up the mountain. It started snowing, and by the time we got up to our shelter, the shelters were full. So we tented out overnight. Luckily they had a Ridge Runner. That is someone who is paid to hike along and check on people and talk about best practices, specifically Leave No Trace.

The Smoky Mountains have an interesting system. People who are doing section hikes have to reserve the shelters they’re going into, while thru-hikers have a general pass – it’s a little cheaper and you’re able to go for a longer period of time, while the section-hikers have maybe three days, at most for that section. They have to reserve specific spots. Thru-hikers always go in the shelter. But if the shelter is full, and you’re in that shelter, and a section hiker shows up, you, the thru-hiker, have to go out of the shelter and tent up. Section hikers are not allowed to tent. Again, you can find yourself in a precarious situation, especially if it’s cold or raining, when everyone wants to be in the shelter. That was when it dipped into the low thirties, mid-twenties. It was cold enough that, sleeping in my tent, the only thing that kept me warm were hand-warmers. A twenty degree sleeping bag just means you’ll survive at twenty degrees, not that you’re going to be comfortable. I was frigidly cold and the only way I was able to sleep was by holding the hand-warmer to my chest and letting my heart circulate the warmth to the rest of my body. I had all of my clothing on — two pairs of clothes – and anything else, like two warm hats, gloves. I had all that on. I was bundled up, so I was able to sleep. The following morning when we got up there was snow on top of the tent. Taking down the tent was extremely cold. My hands were extremely cold. My friend had a form of hypothermia, a condition where if your extremities get too cold you get nauseous. She had to go sit in the shelter for a while. She was worried she was coming down with something, but the Ridge Runner, who’d spent the night there to help out hikers, informed us what was going on. This was at the first shelter in the Smoky Mountains. That was the coldest night. It was absolutely miserable. But we lucked out.

There are certain places in the Smokys, like at New Found Gap, where a road intersects the trail. There is a heated public bathroom there. When it snows, the rangers send word that you have to get off the mountain — only the rangers are allowed to drive up that road. It’s dangerous. Hikers can’t get off the mountain, so they have to sleep on the floor of the bathroom. There was one hiker who got her trail name, Queen of Thrones, because she was trapped there for a couple days. Another important factor in a situation like that is, if you need to get food for the next section of trail, you are going to have to wait there, because you can’t do the next section without food. There was an instance where a group of around twelve hikers got stuck there and needed to resupply, but they couldn’t move because of the snow, and they all got sick because they were sleeping on the floor of the bathroom.

Were you mostly alone?

Yes

Was that true of most of the hikers?

That kind of depends on people’s personalities. What happens on the trail is you gain a ‘tramily’, a trail family. My friend and I hiked a little under half the trail together. We found we had different hiking styles and were starting to argue about things, so we split up at that point. But other trail families were really starting to congeal by that point. I’m thirty five. I wasn’t there to meet new friends. I had a lot of great friends at home. I wasn’t looking to bond with a bunch of people. It kind of depends on what you’re trying to get out of the trail. A lot of the people who were in their early twenties, they were still in that high-school/college age mentality of looking to find kinship and friends, make new ones on the trail, party – stuff like that. But toward the end of the trail I did have a fun scenario on the Hundred Mile Wilderness. It’s essentially a hundred miles of trail with no side trails in between. You can’t get off, so you had to provision that amount of food for that time span. Everybody’s nervous about that section, but it’s really not that bad a section to go through because, overall, it was a gentler section. I happened to get on pace with tramily of about twelve people, and they were really very nice people, but it made it hard for me because if you lined yourself up with that family, you knew twelve spots in the shelter and camp site were going to be taken. I was kind of juggling back and forth with them. That was the last leg of the hike. You do the Hundred mile Wilderness and then you’re about ready to go to Mt. Katahdin, which is the very end of the trip, and it was nice to hang out with people. I was trying to find a balance. Some of the people in that tramily were people I’d met at the very beginning of the trail. It just happened that we lined up, that we saw each other again at the end.

What is your take away from this trip? …The important thing?

I’d say the one thing I really liked about the trail was the sense of minimalism, having everything you need in your backpack, not having a home. You kind of get a sense of survivalism. Up to that point I’d always had a home to go back to – of course, don’t get me wrong, I always had a home to go back to while on the trail – but it did play into that factor, of feeling “oh hey, I have everything I need here.” The sense of independence you get doing it — that was very nice. Another aspect that is also a favorite part is the idea of getting yourself out of your element, of breaking yourself out of going to a nine to five job, away from sitting in front of a computer every day, of getting a different perspective on life. There are definitely a lot of people who hike the trail, and it changes their whole perspective.

Did You?

No. And that’s where I would highly recommend, if you’re thinking about doing the trail, and you’re younger – just out of high school or college – those are the peak times to hike the trail, because those are your formative years when you’re deciding what you’re going to do as an adult. For them, it really does inform their perspective. But for me, it reaffirmed how good things were at home, that I really enjoyed the way I was going. I had been just miserable at my job, and once my job was gone I was perfectly happy! And these past months when I’ve been staying home and looking around for a job, I’m still happy. It’s reaffirming for me. Whereas, for some, it changes their whole life. They go into the van life. They just want to live in a van for a while, become nomadic. They get drawn to the appeal of these trails. It’s not very expensive to hike the trail. You can do it for as little as three thousand, or as much as ten, depending on what luxuries you want, what food you want to eat, those little factors. I’d say it was the cheapest I’ve ever been, hiking the trail. You’re getting your enjoyment out of walking. Which is free.

Ah Ha moments?

Sure — ( l o n g p a u s e ) — I thought I might find some sort of extra spiritual connection, or something about myself, but really, it just affirmed how happy I am at home and with what I have. It did push me into thinking “I just can’t wait to get towards retirement, where I don’t have to work anymore!” (laughing). OK. I know my goal! One of the things I was thinking about throughout the trail was: What do I really enjoy doing? Am I on the right career path? Should I change at all? I was doing system administration. Currently I’m trying to get into database administration. It’s not quite the same field, but it’s in a similar vein. I think I’ll enjoy that a lot better, even if I get paid less. What I’m thinking about is – you can have a high stress job, and get paid a lot, and retire early, but will you have your health if you do that? Or do you want a lower stress job that might not pay as much, but you’ll be happier over time? That was the balance I was thinking about on the trail. That was partially why I did the trail. I wanted to take the time to do that thinking. It was very informative for me, because until hiking the trail, the last time I’d taken more than a month off from work was in high school. It was very different to not be working.

Did you take pictures?

Oh, lots! It’s important, once you’re off the trail, you can get depressed when you’re not seeing new sights every day, and not working out twelve hours a day (laugh) – which I’ve staved off so far. I was lucky to have a lot to come back to, my wife was at home, a house, my cats, and my family – all those things that I really missed. Those were the things that midway through the trail got me really depressed. I’m finding, more and more, that I’m really happy when I’m home; happy with what I have. Where, the young high school and college graduates, with only what they have on their backs , they are coming back to “what do I want to do?”, “where do I want to go?’ — to a whole new world.

This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks,

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.

Loud from its rocky caverns, the deep-voiced neighboring ocean

Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the forest.

Evangeline, by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

by Elsa Johnson and John Cross

A friend of ours — young by our standard, but not his own — spent last summer hiking the Appalachian Trail. We thought our readers might enjoy this conversation with him about his experience. The lead-in question was:

So — How many pairs of shoes did you go through?

I went through four pairs of shoes. The trail is around 2,200 miles, so I went through a pair of shoes every 500 miles.

Clothes?

No – just some holes.

Why did you do this?

Originally I was looking for a way to channel something outside of work that wasn’t my day to day, and I’d always been into hiking; it was a way to disconnect. I’m a technology person. I wanted — wilderness. That was important, to have something that was completely separate from technology. I was stressed out from technology. I started realizing how there’s kind of a gear-head culture around hiking, where you’re trying to get your gear as light as possible, and it specifically pertains to these thru-hikes. That’s what got me thinking about the Appalachian Trail. I had two friends who’d hiked the trail – a section, not the whole thing – so I started thinking about the trail and what gear should I purchase and how could I get it light? There are these luxury items that you don’t really need, but want to have with you, like a large battery pack. It’s not really necessary and mine was heavy at 12 ounces, but it adds a lot of convenience, like always being able to charge your phone. Then I just got the Big Rosy Glasses about the trail. I liked that it was a long linear hike, a point A to point B destination. I wanted to do something that broke up the monotony of what I had been doing, working thirteen years right out of college. I wanted to change that up, make sure I was not missing out on something — not just work until my 50’s or 60’s, and then think “oh shoot, I lost that opportunity.”

Why do people start in the south and hike north?

What I hear is it’s a little bit easier that way. Hiking the whole trail depends on timing. If you want to start in the spring, then you want to start in the south. But if you are only available to start midsummer, then you will want to go southbound. What enticed me was that supposedly it eases you into the harder part – you’re getting what they call your trail legs. By the time you have your trail legs, you’re getting into harder terrain.

How long did getting your trail legs take?

(laughing) It depends on the person. It took me about two months before I was hiking at a good pace. The other thing to balance out was calories, how much food one can carry, because carrying food is heavy. You want to be sure you keep your energy up and nutrients correct because that can cause issues as well. I eased into the trail. At the beginning I was doing 8 to 12 miles a day. Then every few weeks I’d go a little further, or it was an easy day.

What’s the longest mileage you covered?

Twenty seven and one half miles. That was in the Shenandoahs in the northern end of Virginia; they are known for being relatively flat and easy, so that was the section where I was pounding the miles. I found out after the Shenandoahs that I was very calorie deficient. At that point I was prepping for what’s called the half-gallon challenge, where you eat a half-gallon of ice cream in one sitting. I discovered that instead of getting burnt-out and a stomach ache I was getting a sugar rush, and I’d hike a lot further when I put in all those ‘empty’ calories.

Where did you start?

That was in Amicalola Falls, Georgia. That’s the approach trail in and it is about 9 miles. Then you get to Springer Mountain and that’s the official start of the Appalachian Trail.

What struck you about the early stages of the trail?

The biggest thing that struck me early on was how crowded it was. There were a lot of people on the trail. Back home people were thinking “oh – John’s alone in the wilderness. Anything can happen. It’s scary, and he’s stuck there.” I think the least amount of people I saw in a day was three, and typically more like ten to fifteen. At the beginning, at every camp that we stopped at there had to be twenty plus people. There were day hikers, section hikers, and thru-hikers. It was to the point where we were concerned we’d find good spots to camp out. You can also do what’s called stealth camping, which is, in certain parts, you can camp off the trail. But we wanted to stick to the shelters. They have conveniences, like bear boxes to put your food in, instead of just hanging it up. Yes, bears may be attracted to the shelters because there are so many people leaving things, but also there are so many people that a bear wouldn’t mess around.

Did you see bears?

Yes. About nine. My first bear experience was scary. I think it was in North Carolina. I’d just set up my tent. I’d sat down in my tent and was ‘exploding’ my backpack, taking everything out and getting arranged for the night, when I heard this person-sized thing coming up behind my tent. I knew there were no people behind me – so I slipped out and stood up, and there was an adolescent bear staring at me. We both got spooked. He went about ten feet away, and stopped, and stared at me. At that point I’m like “what do I do?” I took out my backpack and food and left my tent completely zipped open, and walked away from him. He sat there awhile. We tried to make loud noises to get him to go away. Eventually he sauntered off.

You had a friend with you?

Yes. I wasn’t entirely alone. That was the thing about being in a camp with so many people. That bear was a little nerve-wracking. We went around the camp and told all the people to hang up their bags on bear cables – that’s a rope system that’s provided. Some people still didn’t hang up their food, but it was so early on that people were just getting used to being in the wilderness, and hiking, and a lot of people were still sleeping with their food, which is the opposite of what you are supposed to do, because bears are going to be curious about you. Luckily, that night we had no disturbance, but I didn’t sleep well. I didn’t move my tent. It was one of those things; once I ran into that first bear I realized that I had to accept that there are going to be bears in the wilderness, and I had to get word to them, and be on the alert. Luckily I had no bad encounters with bears, but that definitely was a near encounter. When I’d get the most anxious was when we’d go into popular areas that day hikers or weekend hikers used, who would not be as mindful about storing their food properly. If they lost their food they didn’t care, and that was when bears would get habituated and start to associate people with food. I know they did have to kill one bear while I was hiking the trail. The story goes that the bear had gotten to the point where a hiker had put down his pack and went off-trail to go to the bathroom, and when he was coming back to his pack on the trail the bear rushed it and tore it open, ate all the food he could, and then puked up all the food on the hiker’s backpack. At that point your backpack is your home. It has your tent and everything in it — and at that point you know that bear is going to be a problem. Or sometimes you’d hear from people going to or from certain locations that there were bears in the nighttime, slowly getting habituated. That was what I was scared of.

Did you see any other potentially dangerous wildlife?

I saw a lynx. I’d stepped off the trail to go to the bathroom, and as I was walking back to the trail I saw, about 20 feet ahead, the back end of a lynx walking away. It was stalking me, most likely, because I was the only thing that was there. I was on high alert, because with cats you can’t back off if they attack you. But really, there was no danger. The trail itself was the dangerous part.

The little section in the Tennessee Balds that my husband and I hiked, in the Smokies in 2018, was like trying to hike up a waterless waterfall — the steep pitches were so rocky and uneven. Is most of the trail like that?

Yes. But it depends. Going from the southern to the northern end, it gets harder the further north you go. The southern end — this is the rosy glasses part – really wasn’t that bad, overall. Sometimes you had to get used to parts that you were hiking up, and sometimes it was really wet. I think my wettest day was in Pennsylvania when the trail became a stream, because it was raining so hard. Pennsylvania is known as the rocky state. That was where I got most depressed on the trail. There are so many rocks on the ground that are a little bit bigger than fist size, all along the trail — It’s a section where a lot of people twist an ankle, and there aren’t so many spectacular views in that state, either. I didn’t feel like I was working myself forward toward something rewarding. I felt like I was just passing through this brutal trail, and the higher mountains were fewer and farther between than in the earlier states (Georgia/North Carolina/Tennessee/Virginia). They are mostly in the east of the state, where you leave Pennsylvania and enter New York. That’s where you begin to get into the real mountain climbing part of the trail — which I was expecting, but it’s different when you’re there in person. My first taste of that was in Pennsylvania at Lehigh Gap. It was the point where you had to put away your trekking poles (I used trekking poles the whole time; I recommend them). It was just hand over hand climbing up these big boulders up the side of the mountain, and you have your backpack pulling on your back, and then there was one point where you can look back, and it’s like looking down a cliff — very scary. I’m not fond of heights. But I knew that going into it. That was my task that day. I wanted to get off that mountain as quickly as possible, from point A to point B, and just keep going.

Is it as bad going down the other side?

It was, give or take.

by Elsa Johnson and John Cross

One of the nice resources that I got very used to, where techno influences hiking now, is an application called Guthooks. Essentially it uses the GPS on your phone to figure out where you are at any time along the trail. You can see where the next shelter is, how far you are away from water, and it allows people to leave comments on key points, so it was a good way to figure out “how hard is this next section of trail?” Once the north-bounders and south-bounders were intersecting, you got a nice sharing about how hard something would be – but also you could be thrown off a bit. A south-bounder could think a section was hard, because they were going up, but a north-bounder would think it was easy because they were going down.

Though sometimes down is harder…?

Yes! In New Hampshire and Maine the trail became very fond of these forty five degree rock faces. Going down it was a whole different ball game. Scary. You’d have to brace yourself – sometimes scoot on your butt and hope you don’t tear open your pack, or hurt your hands. That was the safest way.

What were the prettiest parts of the trail?

I have two favorite parts. One held the favorite spot for the longest time, until I got to the other. That was Roan Mountain, North Carolina. That’s the area called the Balds – just a gorgeous area. I loved those trails, when you can go up on top of the mountain and can see the trail across large expanses – huge expansive views — as you’re walking along. It was a complete reward to be hiking. That was my favorite until I got to New Hampshire, in the White Mountains. The Whites were extremely difficult. I’d be going through a difficult area, and there would be a family of four with a ten year old and a twelve year old; it kind of put you in your place. Mt. Lafayette – that was my high point of the trail. It was absolutely gorgeous up there. It was three thousand feet up, in a relatively short period of time. But once you’re up, the views are gorgeous. You can see from one mountain to another, to the Presidentials in the distance. The Whites in general are very gorgeous. It was much like in the Smokey’s. As a hiker going through, you almost get a little dulled.

How long did it take you to hike the whole trail?

It was a little over five months. I started April first on the approach trail and finished on September 9th. Which was about right, because when I was at home, planning, doing my spread sheets, I was trying to average thirteen miles a day, not accounting for what hikers call zero days, when you stay in town and don’t hike at all. Based on that, I ended ahead of my schedule. It was about half way, at the Pennsylvania mark, where I started to feel I’d had enough hiking. I still wanted to see all the sights – take that opportunity – but I also wanted to get back home. Most people don’t get the opportunity to take a hike like that. Anybody you talk to who has only been able to do a part of it and gets off, for other than physical reasons, regrets doing that. They wish they’d pushed harder for it. I knew going in that even if I felt miserable, I was going to push myself to the end.

When you were hiking how did you and Corey (John’s wife) manage? Did she drive to visit you?

Luckily Ohio is kind of central to the Appalachian Trail. Yeah – She drove me and my hiking friend to Georgia, and hiked the approach trail with us, and then drove back home. She was just a trooper. She drove a lot of miles to visit me throughout the trail, and she picked me up at the end of it. Other times were scattered, when she had time off, and I had a town I was going to that was convenient for her to drive to.

Does the trail go through any towns?

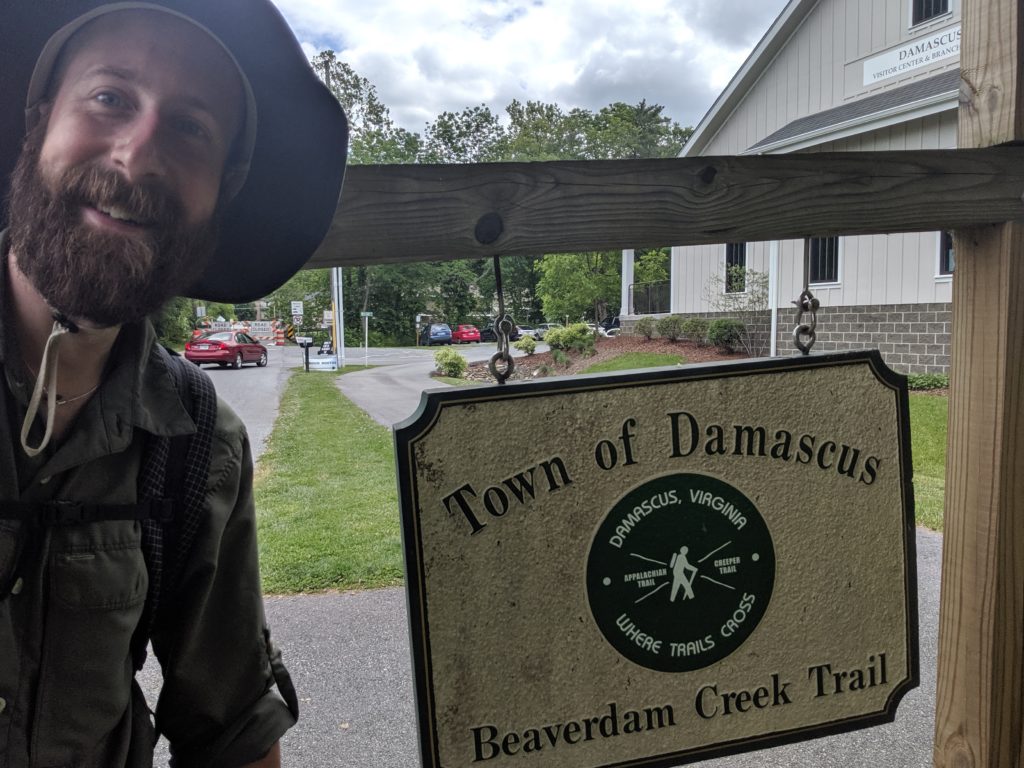

Most of the time you have to get off the trail. Typically it’s only a mile off the trail, but sometimes five miles off. In the south the popular hot towns that the trail goes through are Hot Springs and Damascus, as well as a college town in New Hampshire (which I should remember but don’t!). In the northern states when you go into town you’re like a fish out of water, especially going into big towns, because when you’re hiking the trail you can smell people from a mile away. A lot of the smaller towns, the trail towns, kind of flow with the seasons. A really good gig to be in is the hostel business. In the north the hostels have both a hiking season and a skiing season that offset their costs, and the off-season, when they have time off. It works out well for them.

What about the people you’d meet?

Typically trail hikers have a nice mentality to them. Generally they’re kind – everyone is trying to pay it forward. And you run into a lot of ‘trail magic’. Especially in the south, where charities or a church group set up at an intersection where the trail crosses a road, and hand out candy, drinks, soda pops. I ran across one where they were making burgers, even veggie burgers for vegetarians, and fresh cut fries. I went past those countless times. If I lived close to the trail I would totally do that because on a hot day when you see someone with cold pops – that’s the bee’s knees, so wonderful. You really start to crave the luxuries of home, like air conditioning, ice cold drinks. Showers are a wondrous experience when you’re getting off the trail, especially if you’ve had several days of rain. The rain kind of washes you but you feel dirty, especially if you’re going through mud. But yeah – Trail Magic was just the most wonderful thing! I ran into folks who do it because they love to see hiker’s faces when they come out of the forest and see food.

Did your phone work the whole trail?

It was spotty. I brought a GPS. A Garman Inreach Mini– light, but it was expensive; it costs about three hundred dollars, and then you have to buy a monthly subscription that runs from ten dollars a month to up to sixty. GPS works with clear skies. If it gets cloudy, it get a little wonky. When it came to the phone, sometimes Verizon would be the best one and sometimes AT&T. You could not be guaranteed to have cell service. It was very problematic when you were trying to go to a town – sometimes you’d be five miles away from it and you’d need to figure out a ride, and you didn’t know, going down the side of the mountain, if you’d have reception to call into to town to get a ride – or if you’d have to walk a road into town, which, after trail hiking, was very painful on the feet. Even though its flat, it hurts quite a bit. One thing people don’t know is that your cellphone GPS works even if you don’t have reception. I’d put it on airplane mode, and then use the Guthooks app to figure out where I was at any time.

When you got to shelters – did any of those have showers ?

Very rarely. There were a few, about four of them.

…water?

The shelters were typically placed close to a stream.

And that water was safe to drink?

Yes. And no. In the more popular places it would have been tested. It got a little trickier when I got into the northern states because that was when I got into the peak summer season, and a lot of the seasonal streams started drying up. That was another place where trail magic came into play. As I got into New Jersey and New York, one of the luxuries and pure kindnesses of people was they’d leave out water jugs for people to take and be able to fill up. That’s probably where I had to drink some of the dirtiest water, where you’d filter it and it would still have this murky color to it, but you had to use it, because you knew in advance some of these other water sources were not going to be there, and the last thing you wanted was to go without water. There were some instances – at least two that I can think of – where the Appalachian Trail Conservancy has care takers, who stay and maintain the enclosed structures. Those have water that you can take, and showers. Oh – more than two. I didn’t go to the ones in Maine.

by Mark Gilson

Witch hazels arrive early to garden parties in the Midwest, too early for some gardeners! Put on your winter coat and muck-boots to catch their colorful shout-out, mostly in early March, before the forsythias and hellebores! Although their early-spring blooms may be inconvenient for the faint of heart, they are delightful, fragrant, fascinating and well worth the trip outside!

How does a winter flowering shrub become pollinated? Actually, this occurs through the efforts of a ‘shivering moth’ that makes its rounds on cold nights. Earnest palpitations raise the moth’s internal temperature by as much as fifty degrees!

We are lucky to have a plantsman and wholesale nurseryman in Madison, Ohio, who makes it his business to collect and grow these under-appreciated shrubs: Tim Brotzman, Brotzman’s Nursery. Tim invited us to his nursery on a cold muddy Saturday in early March 2019, a perfect day to witness this private pageant! At the beginning of the long spruce-draped drive leading to the house that Tim built with his father, we find two bright yellow sentinels, Hamamaelis xintermedia palida. My wife and I were unescorted at this point and thankful for the labels! Each blossom on a Witch hazel is remarkable, only an inch or two wide, tiny colorful streamers exploding like party-poppers from tight centers all along the woody stems. Flowers may accompany dried fruit capsules that popped the seeds up to thirty feet in the previous fall. Tim says horticulture makes us better observers. As we catch up with him and hike through the orderly fields, he introduces each new plant, witch hazels and other friends, as treasured personal companions, with stories of their idiosyncrasies, temperament and original collection. For an hour, we were fortunate to be the ‘shivering moths’ visiting each plant in the collection.

Tim began his horticultural education working for his father, Charlie, a renowned nurseryman, story-teller and poet. After earning a degree from The Ohio State University in the early 1970s during the golden age of OSU Horticulture, Tim studied in England and Germany. He worked with David Leitch, local world-famous hybridizer of rhododendrons, as well as distinguished plantsman at The Holden Arboretum and local nurseries. Somewhere along the way, he traveled to Tibet on a plant-gathering expedition. Among the legendary International Plant Propagators Association, Tim is recognized as a ‘fellow’ for his years of attendance and service. The best thing about Tim is that for those with any connection to horticulture, he celebrates and extracts any knowledge and experience, no matter how limited! Talking with Tim, whether a plantsman, local grower or master gardener, you are elevated to a revered place in a fundamentally important industry and pastime.

The fall-blooming Hamamaelis virginiana is native to the Eastern and Southern US. Find it in shady woods on your autumn hikes, sometimes clinging to the side of woodland ravines. Native Americans utilized it for treatment of various inflammations and tumors. A derivative is used in Witchazel’s Oil. Hamamelis Mollis is more common in the nursery trade than the native fall-blooming form, although that is changing with renewed interest in native plants. H. Mollis was crossed with H. japonica to form many cultivars of H. xintermedia common to the trade. Red-flowering varieties were selected by early developers, including Hamamelis xintermedia ‘Diane, ‘Livea’, and ‘Jelena’, all of which Tim pointed out. ‘Arnold’s Promise,’ brilliant yellow, remains one of the popular cultivars (although Tim discounts any connection to the body builder and former governor of California!). Other varieties include ‘Glowing Embers,’ ‘Strawberries and Cream,’ and ‘Orange Peel.’ There are also vernalis types, including H. v. ‘Kohankie Red.’

Tim shares detailed origination data on all his plants, including one he collected from within an armored gunnery live-fire range in Louisiana (Tim’s friend, Tony Debevc, Debonne Vineyards, flew him there in his own plane). As we walk among the rows, Tim trims flowering branches with his well-used Felco clippers for us to enjoy in our home. We comment on the odors of each, from cinnamon to apple to a pleasing but obscure vernal scent. As so many plants in our gardens are bred these days for color and other characteristics, it’s great to put our noses to work again!

Recent cold winters were hard on the Witch Hazels. One year the local temperatures dropped to 30 below zero, followed by a wet year, followed by a March with a precipitous drop to minus eight degrees. Some of the casualties remain evident in the field. Others returned to life amidst a bundle of low stems. Each cultivar seems to require its own regimen, some seed-grown, most grafted. We wonder how all this hard-won knowledge will be transferred on. Tim is no longer a young man, despite his customary energy, wit and positive engagement. Documentation of our horticultural experiences remains a challenge for our entire industry!

Other gardening treasures abound along the edges of the Witch hazel trials…columnar white pine…a beech seedling from China that has proven unsusceptible, so far, to the mysterious ‘beech blight’… unusual pines…dogwoods…many one-of-a-kind specimens.

As a businessman, Tim is consumed with inventory matters, how to record, promote and price the myriad wholesale stock in his fields. We value the time he took from his busy day to provide these precious moments…always too few in the day-to-day chaos of our chosen fields…for horticultural observation, appreciation and instruction!

by Sonia Feldman

Day Four: Visit Hever Castle Gardens, lunch at Beaverbrook, return to London.

Hever is a castle in the most romantic sense of the word. Dating back to the 13th century, the structure is double moated, lavishly decorated, home to a 100 year old maze with walls made of Yew and the site of amorous, historically significant intrigue. The castle served as Anne Boleyn’s childhood home, and in 1526, when King Henry VIII began his pursuit of Anne—a courtship which eventually led to their marriage, her coronation and finally her beheading in 1536—he did so within the walls of Hever Castle.

Yet for all its drama and historical significance, Hever is surprisingly small—the size of perhaps a very large mansion by today’s standards. The rooms, though beautiful, are not very large. Most have low ceilings and limited windows. There is a coziness to the castle which humanizes the stories of international political intrigue that took place within its walls. You can imagine Anne living at Hever because you can imagine yourself living there.

Here I have some good news: you can—at least you can stay the night in very close proximity. Two Edwardian wings, designed in the Tudor style and originally housing the castle staff, have been converted into a luxury bed and breakfast on Hever’s grounds. The rooms have beautiful four poster beds for you to dramatically throw yourself across, dark wood furniture and luxurious Hever Castle letter writing paper for whatever amorous missives you may wish to compose.

Most importantly, guests of the castle have access to the gardens and grounds during off hours, which means you can stroll through the property undisturbed by other visitors. Pose with the castle’s fanciful topiary creations to your heart’s content. Enjoy (sniff) the wisteria walk in happy solitude. I particularly enjoyed having the rhododendron walk to myself, a grand grass promenade leading to a waterfall, flanked by blooming rhododendrons.

The gates of the magnificent Italian garden are locked during off hours, but you can still have the place to yourself if you time it right. Enter exactly at 10:30, when visitors are just parking their cars and buying their tickets, and you’ll be able to walk in solitude through the grand marble Loggia all the way until it runs into the property’s 38 acre, manmade lake. Originally excavated by 800 men, the lake took two years’ near constant work to complete (1904-1906). This hundred year old labor yields a spectacular view. On your way back, admire the massive garden rooms set within the marble walls of the Loggia, stopping in particular to enjoy the expansive rose garden and classical statuary (see: the bust of a woman with a hole cut into her stone hat for a flower).

Here begins your return to London and the end of our tour. If you aren’t in a particular hurry, split up the drive with a lunch reservation at the very posh Beaverbrook, a hotel and country club only a few minutes off the motorway. One last beautiful, quiet place before you go home.

Condensed tour itinerary:

Day One: Leave London, lunch at Langshott Manor, visit Nymans, dinner at The Milk House, retire at Cloth Hall Oast Bed & Breakfast or Sissinghurst Castle Farmhouse.

Day Two: Visit Great Dixter House and Gardens, lunch at one of the gardens or return to The Milk House, visit Sissinghurst Castle Gardens, dinner at Three Chimneys, retire to same lodgings.

Day Three: Visit Pashley Manor Gardens, lunch at one of the gardens or Thackeray’s Restaurant, visit Penshurst Place, dinner at The Wheatsheaf, stay at Hever Castle Bed & Breakfast.

Day Four: Visit Hever Castle Gardens, lunch at Beaverbrook, return to London.

Nearby gardens that could be added to this tour: Knole, RHS Wisley, Chartwell, Lullingstone Castle, Great Comp Garden, Scotney Castle, Wakehurst, Godinton.

Sonia Feldman is a writer living in Cleveland, Ohio. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Cultured Magazine, Pembroke Magazine and Juked. She operates an email newsletter, which sends one good poem a week. Find more of her work on Instagram.