by Elsa Johnson

A week ago I went to the Natural History Museum to listen to the speakers at the Ohio Natural History Conference — all of them good and interesting talks (confession; I was tired and slept through two of the afternoon talks; I hope I didn’t snore). They were all short and sweet (20 minutes each), about the relevance and importance of natural history and the natural world, and about the specifics of our changing world, the resilience of it — or not. All of this is just lead in to a lead in; I was much taken with gab-gifted naturalist Harvey Webster’s title for his lead-off talk: “Whither natural history?” and his confession that he had always wanted to use the word ‘whither’ – and now he had.

Whither. An interesting word, archaic sounding and poetical. Whither; meaning ‘where’, as in ‘where are we bound?’ That was the context of Harvey Webster’s question about natural history and the natural world. On a planet with a changing, volatile climate, in an age of extinctions and endangered species and at-risk environments, and I include our own built environment in that — whither are we bound?

There is another whither, spelled differently, but spoken the same; it is whither’s homo-phonic sibling, wither, meaning to become dry and shriveled, to decline or decay. Which seems to be one potential answer or result at the tail end of ‘whither are we bound.’ And when I go there, I am close to despair for what we have lost and must surely lose, and I grieve in premonition of the losses yet to come that I cannot even imagine. That’s when I write poems like this:

A Prayer from the Prayer Adverse

How close despair and prayer lie down in bed

born of the same love and through the same eyes

see both fore and aft : that squirrel offers sun

flowers to feathered gods : that locust sheds tears

as leaves : how mute swan swims in now murky

meres and the strangled oak dies gleaned Through

the same eyes — those hidden eyes — they see

Whither the wild crane and whippoorwill? seals

Sadness to silence and tightens the throat

Despair inarticulate ends all Yet

through those eyes those hidden eyes there may

still come a lightening : a prayer — un-glossed —

if an un-glossed prayer may hope For all

that I love some slight brightening

But that is not, actually, whither I am bound today, and so, having gotten both the w(h)ithers out of the way, time to refloat this raft.

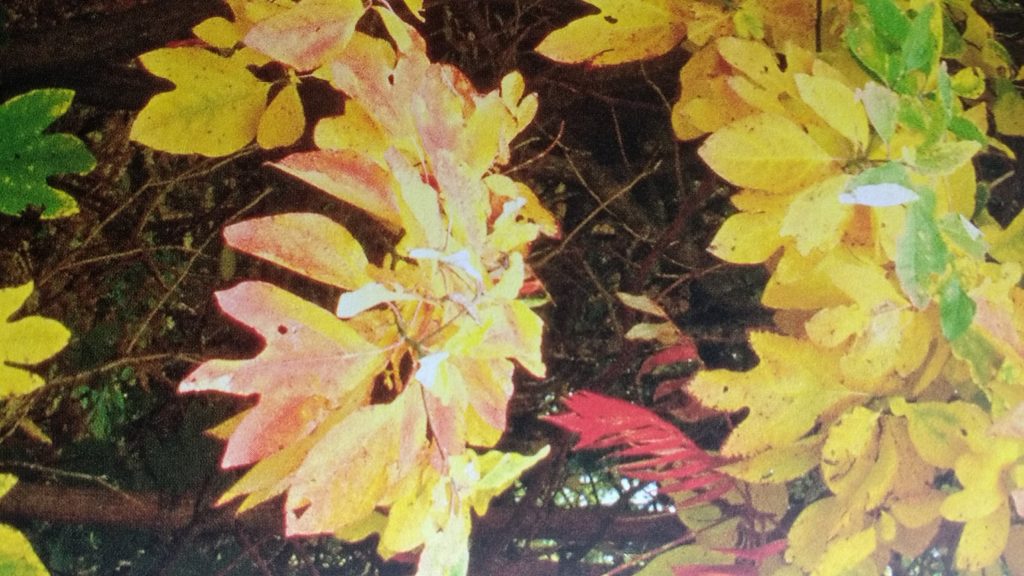

These last mild days have drawn me out into the ‘wilds’ of Forest Hill Park, into the valley, especially the short section where the Dugway Brook flows free in its original channel of layered eroded shales. At the south end, its ‘source’, it pours out of an enormous pipe (large enough to drive a small car into), then flows north for perhaps a quarter of a mile, or less, where it disappears, again, into another monster maw. Here one might well ask of it, ‘whither are you bound?’– for it now disappears again, goes underground into an artificial, and killing, concrete channel, and stays buried thus until it reaches Lake Erie at the eastern edge of Bratenahl, where it at last flows free again, out into Lake Erie.

This short distance free to the air is not enough to restore the stream to life. Before it reaches this unfettered stretch it flows buried under Cain Park, emerges briefly by the swimming pool by Cumberland Park, then goes back underground by the Community Center to emerge again, briefly, for this short free stretch in Forest Hill Park. It is a dead stream. Nothing lives in it. But, in this short stretch of its freedom, it is still beautiful. And when I look at it as I walk by it, I wonder what this area was like when my mother and her father hiked these woods and brooks (the Doan and the Dugway) when they moved here in 1920. I like to think that someday, perhaps, the buried section in Forest Hill Park might be freed, re-aired, re-enlivened — and also, all that is now underground between East Cleveland and Lake Erie, providing again a living life-line for life, and the life of the spirit.

Lois Rose, Gardenopolis-Cleveland co-editor, writes of this little stretch of free flowing stream: “I remember the first time I ever walked the stream bed – I could not believe my eyes. It was like a fairy tale — you stepped out of the parking lot and you were in the country on a stream bed, hidden from view, alone. There is a sense of secrecy. You hardly ever see anyone on it. You do not even know this exists, even though you live a mile away. It’s by the Rec center – yet very far from it. I have a sense of pride in that stream. I appreciate how sad and less-than-it-could-be the stream is – but it has brought me a lot of pleasure over the years.”

And so it has me, also.

Twenty years ago I visited a place in Ireland called Glendalough, a monastic site of some antiquity (6th century). We hiked up into the bracken covered hills there, following a little rollicking brook through its self-carved cloven bed in the rock. Somehow our poor diminished Dugway manages to remind me of that tannen-saturated jewel, both of them with their cascades and rills, and narrow congested places where the water runs fast — leading me to hope that in some future that I probably will not see, some future wisdom and largess will once again set the Dugway free.

I leave you with one more poem, by Gerard Manley Hopkins. It is a better one than my own, in the same way that the stream it describes, flowing into Lough Lomond in Scotland, is a far better brook than our loved but poor and limping Dugway.

Inversnaid

This darksome burn, horseback brown,

His rollrock highroad roaring down,

In coop and in comb the fleece of his foam

Flutes and low to the lake falls home.

A windpuff-bonnet of fawn froth

Turns and twindles over the broth

Of a pool so pitchblack, fell-frowning

It rounds and rounds Despair to drowning.

Degged with dew, dappled with dew

Are the groins of the braes that the brook treads through,

Wiry heathpacks, flitches of fern,

And the beadbonny ash that sits over the burn.

What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left.

Oh let them be left, wildness and wet

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.