—David Adams

People respond so individually to works of art, and one can never be sure where the journey of understanding will begin or end. I am sure that avid gardeners will revel not only in the paintings in this exhibit, but also in the technical details and horticultural expertise shared among the painters. Others may focus on the idea of the garden as a place of solace, so close to our most primal mythologies. As I leave aside the myriad of other possible perspectives on what was, for me at least, a stunning exhibition, I will try to describe a bit of this one poet’s journey, hoping that it might add some small grace to the journeys of others

My first time walking through these galleries of gardens I felt an overwhelming explosion of the senses as the feast of colors leapt from the canvas in such works as these (of course, these thumbnails hardly do justice!). One can almost breathe in the fragrances, feel the touch of wind, and hear the insects flitting back and forth, the hushed voices of humans carrying their watering cans.

| Chrysanthemums, 1888. Dennis Miller Bunker (American, 1861–1890). Oil on canvas; 90 x 121 cm. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, P3w5. |

Images in this article provided courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art Press/Media Kit.

But after the overwhelming response of the senses, other interactions emerge as a dialogue with those long distant moments of creation, at first between poet and painting, then through the painting to the painter. What can I really see here if I just look long enough? What were you thinking as the painting came to rest as what I see? As a poet I might paraphrase Karl Shapiro’s prescient question: What is the poetry of all of that? If the poet has any luck at all, the answers blossom everywhere.

Poets have a long history of ecphrasis, using one of the other arts, usually visual arts, as an inspiration for a poem. John Hollander captures this history well in The Gazer’s Spirit: Poems Speaking to Silent Works of Art. (1995). Of course, even his subtitle begs the question of whether any work of art is truly silent. For a walk through these gardens so strongly resembles the journey through a really wonderful poem that I can scarcely let go of the experience. I can recall two other CMA exhibitions that affected me so, both in 1991. The first was The Triumph of Japanese Style, with its evocative, large painted screens that even had poems as part of the art itself. This show led to a set of “Sun and Moon Landscape” haiku. The second was Reckoning with Winslow Homer, an excursion that unfolded as a complete surprise, one that shattered all my preconceptions about that artist and led directly to one of the longest, most complex and thoroughly rewarding poems I ever wrote. So a rendered garden is also a story on its way to being.

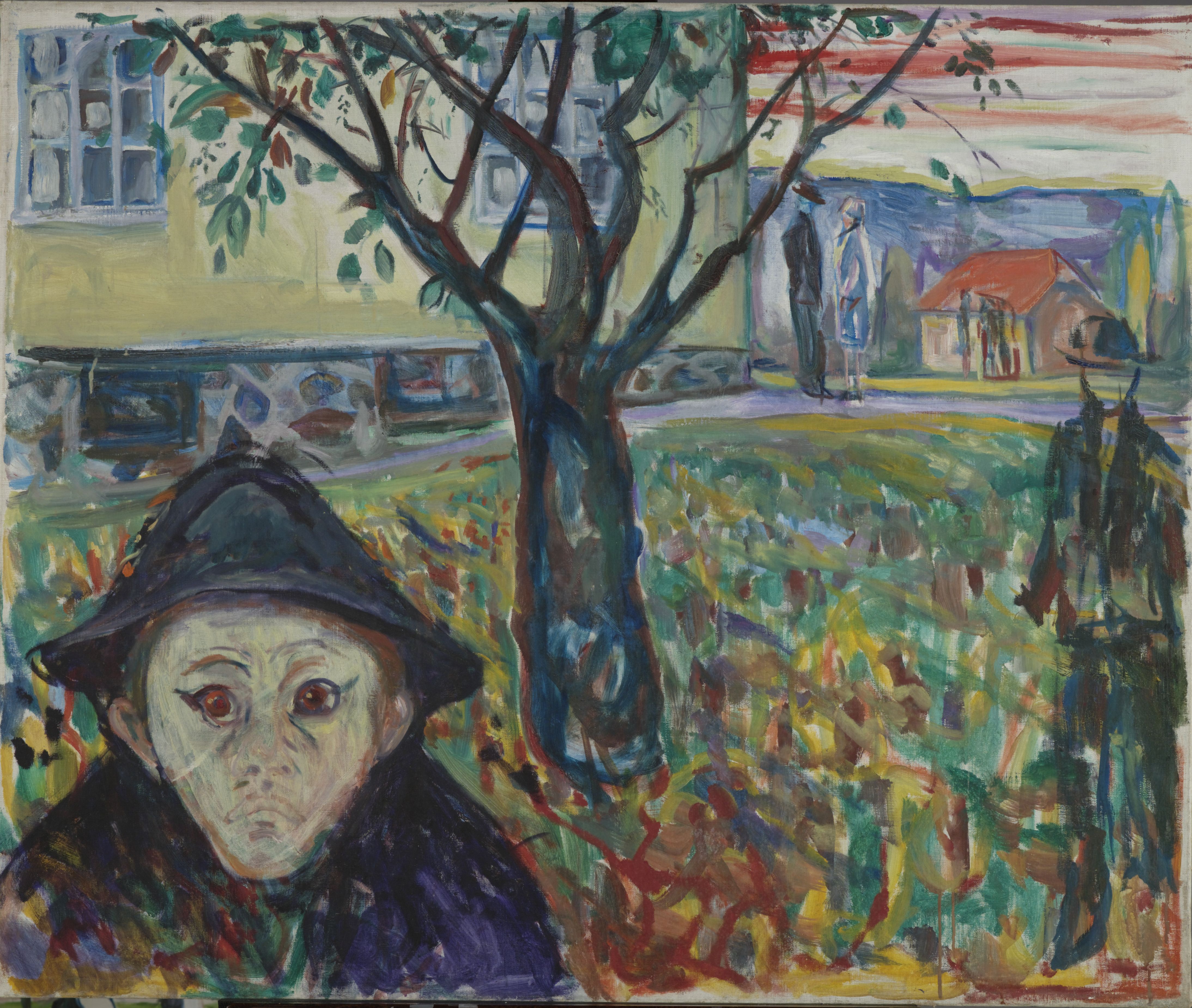

And what can live in such gardens as these? Whatever one wishes, or even dreads. As people become more prominent in the paintings, or as the world outside the garden casts a deeper shadow in them, the stories emerge with greater force.

“Each day brings its toad, each night its dragon.” This opening line from Randall Jarrell’s “Jerome” somehow surfaced during my second view of the exhibit. Jarrell’s poem has as its framework an ecphrasis based on a Durër engraving of St. Jerome and His Lion, but quickly recasts itself as a journey into the life of a psychoanalyst—his aloneness, his solitude, the weight of the night’s dreams, and the solace brought him by the dawn. The extensive worksheets for this poem were preserved by Mary Jarrell in Jerome: The Biography of a Poem (1971). These worksheets reveal how the conversation between poet and work of art emerges and changes the resulting poem as it grows to something like completion. I believe that this sort of conversation lies at the heart of ecphrasis, at the heart of making the poem. One must imagine that painters have the same sort of interaction with their subjects.

| Jealousy in the Garden, 1929–30. Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863–1944). Oil on canvas; 100 x 120 cm. Munch Museum, Oslo, MM M 437/Woll M 1662. Photo: © Munch Museum. © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

The same change in what there is to see seems evident in Münter’s Woman in a Garden or Klee’s Death in a Garden.

| Woman in Garden, 1912. Gabriele Münter (German, 1877–1962). Oil on board; 48.3 x 66 cm. Neue Galerie New York EL. 51. This work is part of the collection of Estée Lauder and was made available through the generosity of Estée Lauder. © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. |

German, born Switzerland, 18791940

Death in the Garden (Legend), 1919

Oil on cotton, on cardboard nailed to wood

10 3/4 x 9 3/4 in. (27.3 x 24.8 cm)

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Randall Shapiro

1996.393

The Art Institute of Chicago

| Death in the Garden (Legend), 1919. Paul Klee (Swiss, 1879–1940). Oil on cotton, on cardboard nailed to wood; 27.3 x 24.8 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Randall Shapiro 1996.393. © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

When works such as these spark responses of such deep wonder, the question is never if a poem will emerge, but rather when it will emerge, how many will do so, and in what fashion. I read somewhere that later artists among the Surrealists and Dadaists felt the works of the Impressionists too constructed, too linear, too distant from the unconscious. That view would seem very odd to a poet just done “talking” with them, pressing the conversation deeper and deeper into the boundless garden, into the making of a painting or a poem—all the shifting lines and changes, the epiphanies and surprises along the way in these works that are never really static, never truly silent, and never the last word.

Bibliography

Hollander, John. The Gazer’s Spirit: Poems Speaking to Silent Works of Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Jarrell, Mary. Jerome: The Biography of a Poem. New York: Grossman Publishers, 1971.