by Tom Gibson

Okay, permaculture is an interesting gardening technique, but what else besides a New Age-y philosophy does it have to offer? Can permaculture really “save the world” or, as Toby Hemenway likes to say, does it smell too much of patchouli oil?

Elsa Johnson and I have been working on a very down-to-earth project that, proves, at the very least, that people who disagree about permaculture can still find common purpose.

It’s the Oxford Community Garden. Since last spring Elsa and I have worked with the gardeners to plan a 6,000 sq. ft. tasting and pollinator garden around the community garden’s periphery.

Click on the following link to see the plan for the first 4,000 sq.ft.:

Pretty neat, huh?

We got there first by building soil with a typical permaculture lasagna mulch [compost, cardboard (to kill grass and weeds), top soil and wood mulch].

In all, about 40 people–both inside and outside the neighborhood– helped. I actually have grown to love these communal work sessions. Some of my regular volunteers do, too. They say,” Call me when you’ve got some mindless grunt work.” What they’re really saying is when you do lots of shoveling and raking as a group, such work becomes deeply (if surprisingly) satisfying.

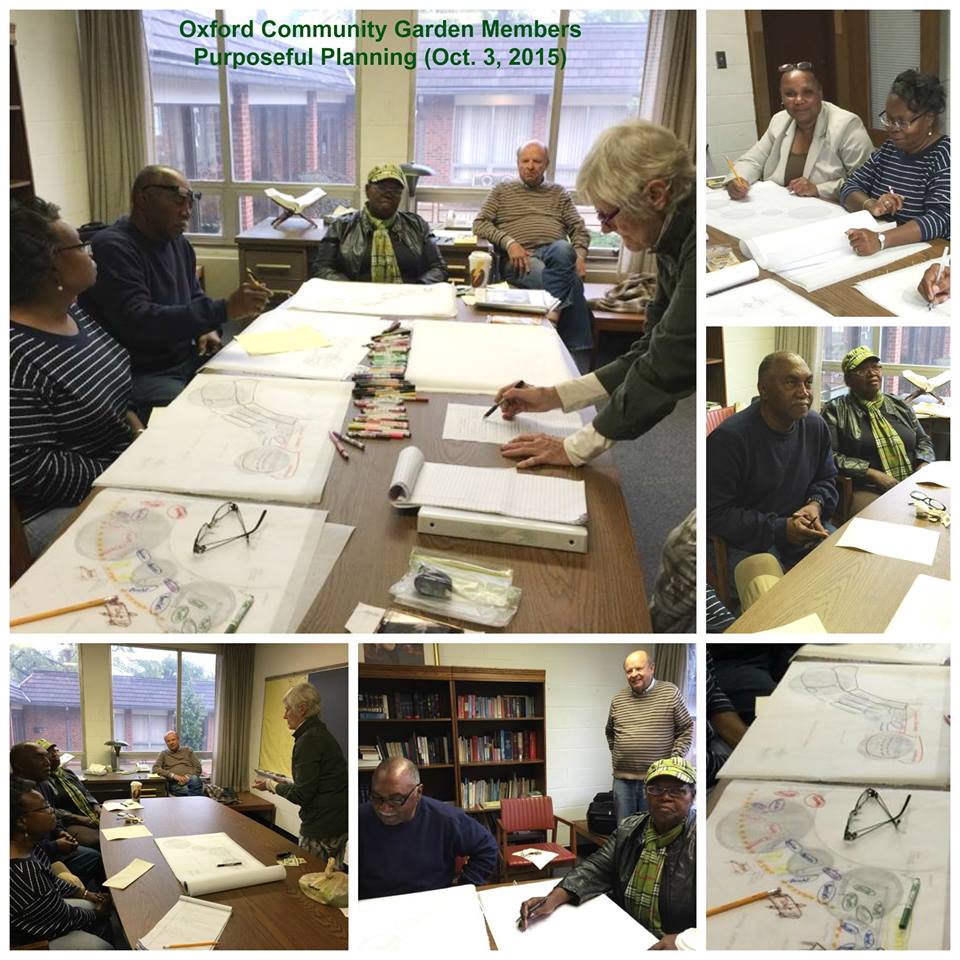

The next part was fun, too. A half dozen OCG members took a four session permaculture course where they learned the basics and each came up with garden designs that for first-timers were pretty good! Elsa then refined their collective ideas up to a professional level–as displayed above. The plan is to establish an addition to the garden that welcomes the neighborhood via a combination of aesthetic landscape, edible perennials, and conviviality-promoting gathering spaces. As Phyllis Thomas, the site leader says, “The new garden addition is something we’ve dreamed about!.”

We accomplished early stage development with seed funding from the Heights Community Congress and the First Unitarian Church, but we’ll need significantly more outside funding to complete the project.

So why would any outside funder be interested? We think the argument is pretty compelling:

1. Shoulder-to-shoulder work of the kind Oxford gardeners and friends engage in is one of the best ways to promote stable diversity. The garden is already a mini-U.N. with half of its membership African-American and the rest a nationality and racial hodge-podge–Eastern European, Indian, Nepalese, Filipino. If there is anything we have learned in the last 50 years about integration is that it only succeeds when pursued actively. Passive integration, even where diverse people of good will choose to live next to one another, inevitably produces “leakage” and resegregation.

2. Permaculture’s most famous saying–“The Problem Is The Solution”–applies to the Noble/Oxford neighborhood in spades. The problem is that despite great structural housing stock the threat of racial resegregation has reduced home prices to disastrous lows–e.g., a $6,000 sales price for a single family, single lot dwelling in decent structural shape! Could this “problem” provide an especially inviting “solution” for prospective eco-pioneers? It wouldn’t cost that much to add solar, on-site water capture, and a mini-food forest as demonstrated in places like Alberta. We’re already seeing early signs that such a transformation could happen. Tremont, the last Cleveland-area neighborhood to undergo bottom-up renewal, has gotten way too expensive.

3. The garden plan links directly–via a “Children’s Garden”– to the adjacent Oxford Elementary School, a lively, hopeful school that is burdened by an “F” rating. The prospect of such a planting space next door has already inspired a worm-raising/microgreen/outdoor planting program just getting started with Oxford Elementary’s first grade classes.

Other schools around the country have reinvented themselves through inspired eco programs. Why not Oxford?

Other schools around the country have reinvented themselves through inspired eco programs. Why not Oxford?

So, smell any patchouli oil? I don’t, either. Maybe we can save at least one small piece of the world!