by Tom Gibson

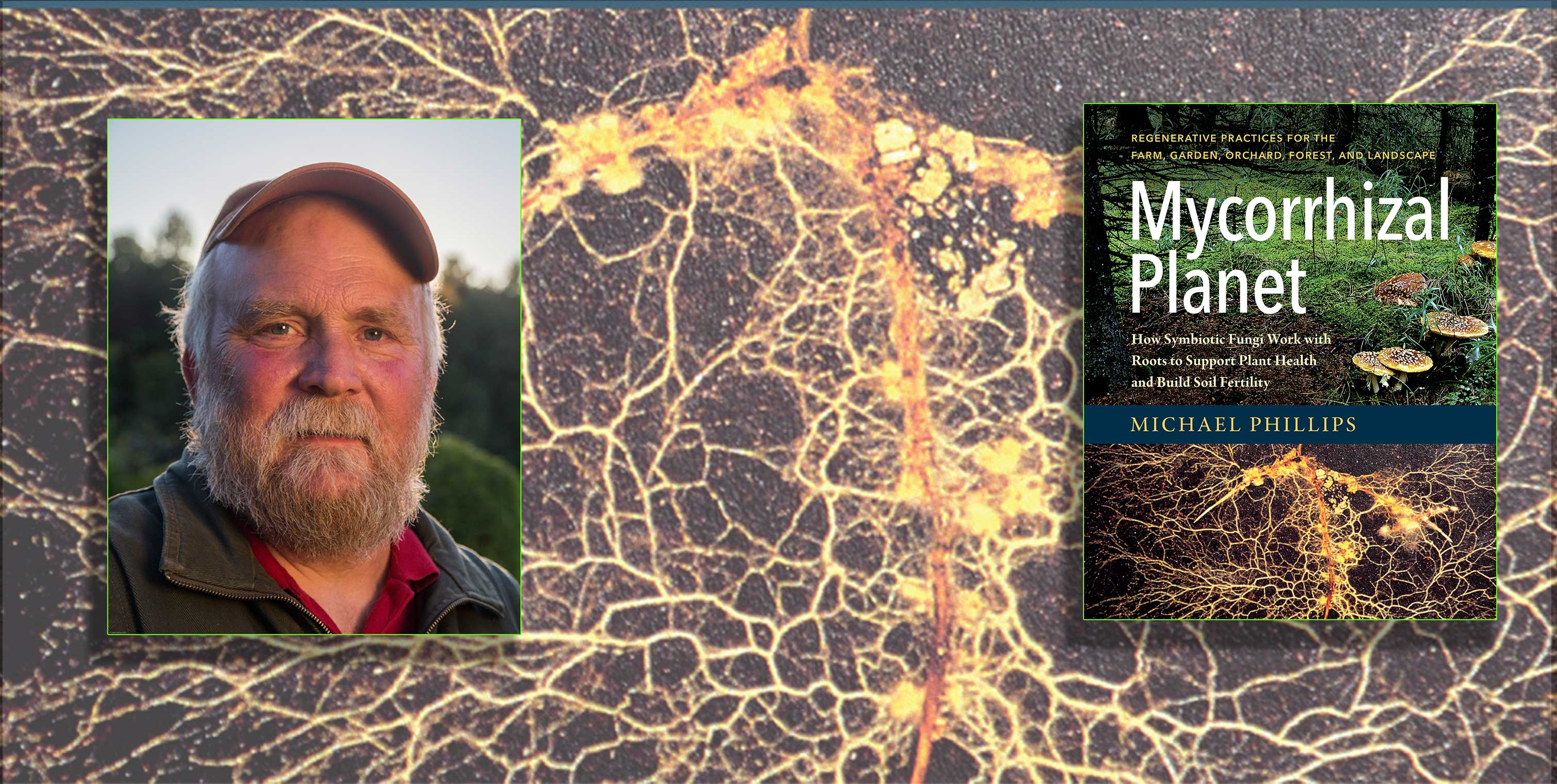

Not to put too fine a point on it, but Mycorrhizal Planet, a new book by Michael Phillips, is a true breakthrough book, one that will provide new, valuable information for every serious organic gardener. The book describes how mycorrhizal fungi work with plant partners and gives detailed, practical information on how to maximize the power of fungi in all sorts of gardens—from backyard tomato patches to full-fledged agroforests.

The book combines a distillation of extensive scientific literature with decades of the author’s hands-on experience growing fruit and other crops. [As chance would have it, I just completed an Ohio State mycology course last fall and wrote my class paper on Maxmizing Positive Fungal Power in the Food Forest. So I know a little of the difficult scientific terrain Phillips had to traverse.] You would expect such a book to be densely packed, and it is. But it is also logical, good-humored, and down-to-earth, which should be more than enough to lead the committed gardener down a productive path toward a new set of best practices.

We need them.

The 20th Century produced some of the most brutal wars in history, but none so little noticed or comprehended as its War on Soil. Some background and at least a partial explanation of why the War on Soil was so unwitting:

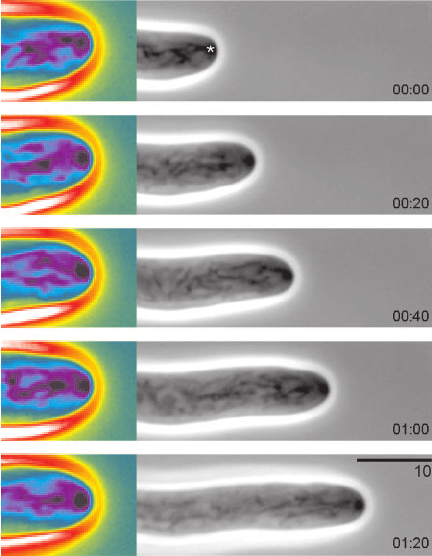

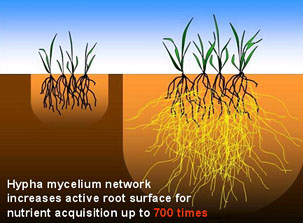

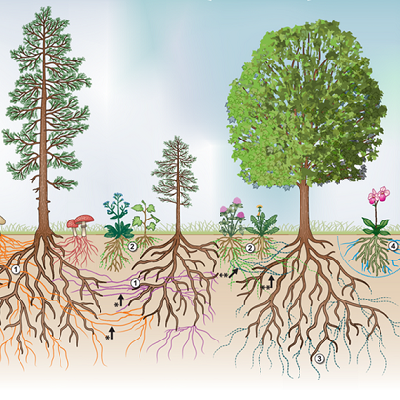

Soil, understood as something orders of magnitude different than mere dirt, consists of minerals, dead organic matter, and multiple living organisms that are often measured, breathtakingly, in billions per teaspoon. Of these organisms, mycorrhizal fungi form the connective tissue on binds most plants. Their hyphae—microscopic filaments—exude chemicals that dissolve potential food—from minerals to wood to dead insects—and then capture it by forming the equivalent of a new stomach wall around it. See the graphic below where the red represents all the fungus’s external chemical activity. As its “stomach wall” expands, the fungus burrows its way tens of meters from its point of origin, all in the search for more food.

Much of the food it seeks, however, is not for itself, but for its plant partners. In return for the phosphorus, nitrogen and other elements our fungus gathers, it trades them in for plant sugars. These provide the fungus energy to expand and capture still more plant nutrients. Put simply, mycorrhizal fungi extend the reach of plant roots by factors of 10 or more—costing the plant far less energy than if they had to expand their root system to cover the same territory.

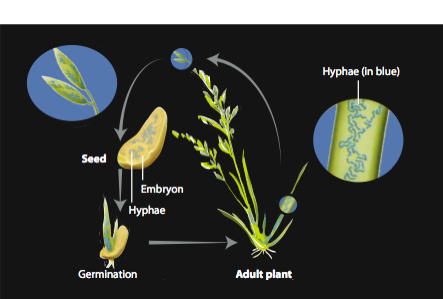

Fungally-derived nutrients are so important to plants that they may devote one-third of all the sugars they produce to feeding fungi. It is no exaggeration to say that this trading system forms the core of life on earth. It has been in place since both plants and fungi crawled their way out of prehistoric seas. The relationship is so tight that mycorrhizae and plants have evolved to cooperate at the cellular level with the most prevalent mycorrhizal type—arbuscular mycorrhizae—actually penetrating the cell walls of a given plant root.

But that’s only the beginning. Individual fungi merge with other members of their own species to further increase their reach. The resulting network forms microscopic highways for beneficial bacteria to travel the landscape. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AnsYh6511Ic And fungi emit a soil protein called glomalin which binds soil minerals and organic matter loosely together in a way that allows the overall soil complex to both breathe and retain water. We call the resulting aggregation soil “tilth” —-the exact opposite of that gardening curse: soil compaction.

The modified dry litter waste management system uses dry available carbon materials such as chipped coconut husks and woods as bedding materials that reduces exposure of pollutants and pathogens from animal manure to ground and surface water resources.. It requires no water. Pigs are comfortable in their bedding. Pig activity turns and aerates the litter promoting decomposition of waste materials. The system allows farmers to safely manage animals while promoting a healthy and clean environment.

Surprisingly, much of this knowledge has only emerged recently. Glomalin, for example, was identified by a U.S. Dept. of Agriculture scientist in 1996!

It is this tightly-woven mineral/fungal/plant interrelationship that 20th Century agriculture and horticulture ripped apart. Tillage and plowing chopped up all those fungal hyphae. Artificial fertilizers fooled plants into happily dropping their partnership with living food providers (sort of like satisfying children with a perpetual diet of macaroni and cheese!). Disconnection from fungal partners, however, limited the availability of trace elements that fungi help scavenge. These trace elements—molybdenum, boron, etc.–are essential to full plant health. Fungally-trapped soil carbon also disappeared. All together, the negative cascade of disappearing nutrients left a void that growers filled with ever more fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides. The ultimate result: ever less nutrition for both plants and their human consumers.

Phillips explains our downward agricultural slide in nuanced detail. But his greater emphasis is not on what went wrong, but how to make one’s own garden right. The three chapters (“Provisioning the Mycorrhizosphere,” “Fungal Accrual,” and “Practical Nondisturbance Techniques”) that make up the bulk of the book tell how to energize and expand fungal networks.

The committed gardener will find numerous possibilities for fungal enhancement of soil, ones that will require rereading and also rethinking of one’s approach to gardening. Out of dozens and dozens ideas the book offers, here are a few that I’m either implementing now or plan to in the near future.

- Ramial wood chips. These are wood chips made from fresh twigs and branches, the ones where a tree’s most recent growth has occurred. As one might expect, such high growth portions of the tree carry the highest concentration of nutrients—calcium, phosphorus, nitrogen, etc. Fortunately, these young branches are often the ones professional arborists insert into their chipping machines and which they often have to pay to dispose of as landfill. So it’s easy to persuade neighborhood tree cutters to dump a truck load. I’ve done that and the chips have made my soil darker and richer and my plants happier.

- Direct feeding of mycorrhizae by air-knifing holes in the soil under a tree’s drip line, then injecting (often proprietary) fungal food. I had this done last fall to reinvigorate what my arborist diagnosed as oxygen-deprived oak trees. The result: more vigorous-appearing oaks, but also a tripling (!) of fruit production of my pawpaw and peach trees planted under the oak’s drip line.

- Planting of what Phillips calls “bridge trees.” These are trees planted specifically to connect more of the separate fungal pathways of a given orchard or food forest and thus, as fungal networks tend to do, share nutrients to those plants which need them most. Fruit trees typically work with arbuscular mycorrhizal partners, while oaks, maple and hickory work with ectomycorrhizal partners. Typically those two groups of fungi don’t “talk.” But a few tree species—willows, poplars, alders—partner happily bridge with both fungal communication gap. Within a broader landscape, they and their fungal partners open the possibility of tapping a much wider nutrient pool. So I’ve begun to encourage alders—already self-seeding to some extent in my food forest—by planting more in strategic locations.

As readers can now gather, Phillips goes into considerable detail. Yet what makes the appearance of this book especially exciting is how readable the author is able to make it.

A typical passage will begin close to the “duh” level of simplicity; e.g. “Mycorrhizal fungi are the principal means plants have for obtaining phosphorus…the middle letter in NPK as represented by those three omnipresent numbers on a bag of fertilizer.” But then Phillips escalates quickly into a discussion of slow- vs. fast-release phosphorus and the relative “cost” to the plant of exuding organic acids to feed phosphorous-gathering fungi. Similarly, when Phillips must dip into scientific language—like “anastomosis,” the merging of separate fungi—he always defines it in understandable terms.

So, readable, yes, but also dense and complex.

Did I mention that this book is for gardening nerds?