by Garrett Ormiston, GIS and Stewardship Specialist, Natural Areas Division, The Cleveland Museum of Natural History

The Museum’s Natural Areas Program

The Cleveland Museum of Natural History is home to a unique conservation program which has protected some of the highest-quality natural sites in Northeast Ohio. This program, known as the Museum’s ‘Natural Areas Division’ was formally created in 1956 with the purchase of a portion of a small bog in Geauga County known as ‘Fern Lake Bog’. This preserve acquisition was conducted under the leadership of Museum Director William Scheele. The natural areas program has since grown to include more than 10,000 acres of land that have been conserved through either direct land purchase by the Museum, or through the purchase of conservation easements held over privately-owned land.

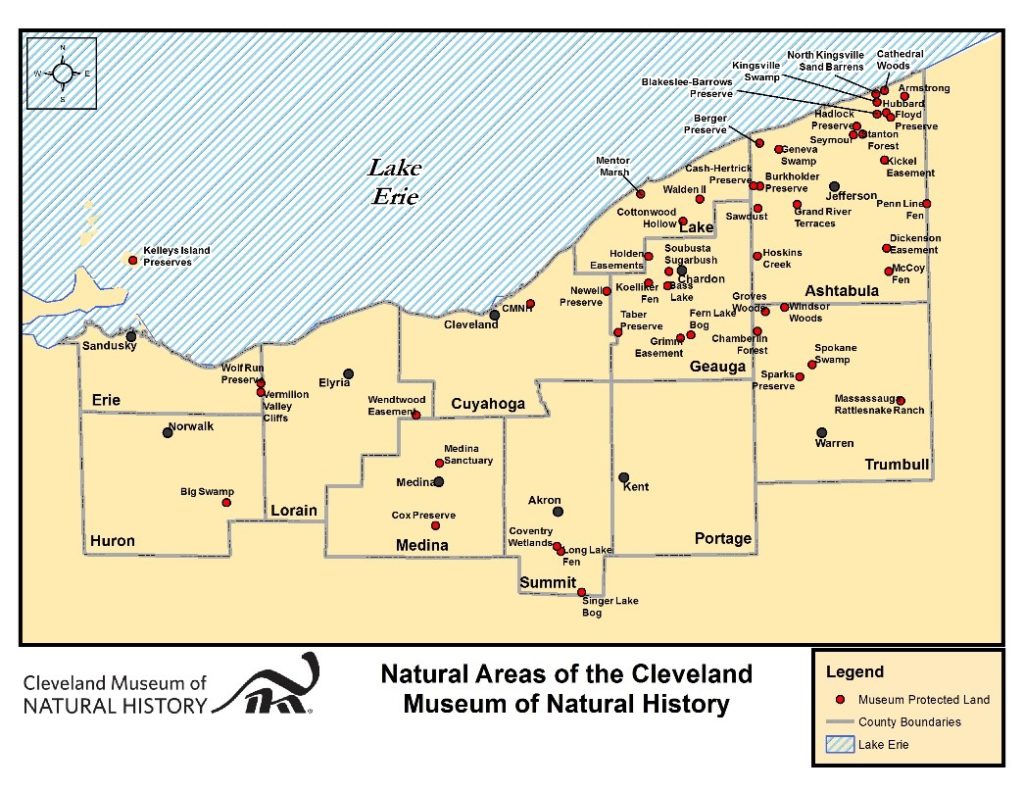

In total, the Museum has conserved 58 distinct nature preserves that are as far-flung as Kelleys Island and the Huron River watershed to the west, the Ohio-Pennsylvania line to the east, and the Akron-Canton metropolitan area to the south. These preserves contain a plethora of different habitat types that are wide-ranging and include peat bogs and fens, glacial alvar, forested wetlands, and sand barrens. Indeed, each preserve is a unique example of a particular habitat with distinct plant communities that existed naturally within our region before European settlement.

The Museum is very focused in its mission to conserve sites that contain unique habitat or that harbor rare species. In Ohio, rare species are listed as endangered, threatened, or potentially-threatened based on the number of populations in the State. The Museum’s program is unique in that its conservation efforts are largely steered by the research and inventory work conducted by the Museum’s staff. For instance, inventory data that is collected from field surveys conducted by the Museum’s various departments is compiled in Ohio’s Heritage Database which is managed by the Ohio Division of Wildlife. It is the data from this Heritage Database that helps determine which species are considered ‘rare’ in the State, as opposed to species that might simply be overlooked or not studied. Indeed, a rare species list is only as good as the data that is fed in to it, and the Museum is the main contributor in Northeast Ohio to the State’s Heritage Database. It is true that the Museum’s collections and research are literally driving its conservation efforts in Northeast Ohio.

The Museum ramped up its conservation efforts significantly around 1980 under the leadership of its Curator of Botany and Director of Natural Areas, Dr. James Bissell. Between 1980 and 2005, The natural areas program more than doubled in size. And between 2006 and the present, the program has more than doubled a second time. Over the last year, the Museum has seen the acquisition of several important tracts of land, which are described in detail below.

Expansion of the Mentor Marsh Preserve

One of the Museum’s oldest natural areas is the Mentor Marsh Preserve which is dedicated as a State Nature Preserve in Ohio. This 780-acre preserve was once a sprawling swamp forest system. Rich silver maple-dominated swamp flats and vernal pools covered the landscape, interspersed with small areas of open water, and emergent wetlands dominated by Greater bur-reed (Sparganium eurycarpum), a species that was likely one of the largest components of emergent wetlands in our region before invasive species like narrow-leaf cattail and canary grass became dominant.

The Museum took ownership of Mentor Marsh in 1965 after a grassroots effort to conserve the site was carried out between 1960 and 1965. The Museum owns the site through a combination of a land transfer and a long-term leasing arrangement with the State of Ohio.

Unfortunately, the biological integrity of Mentor Marsh was dramatically altered in 1966 with the influx of salt contamination from an adjacent site. The water in Mentor Marsh became excessively saline, and caused the trees within the swamp forest to perish and to be replaced by a nearly 800-acre monoculture of giant reed grass (Phragmites australis), a non-native invasive grass that is salt tolerant, spreads quickly and aggressively, and can reach heights of more than 15 feet in a single season, displacing all manner of native vegetation. What was once a diverse ecosystem was transformed in to a landscape dominated by a single invasive species.

Since 2015, the Museum has been engaged in an ambitious project to rid Mentor Marsh of the invasive Phragmites, and to restore the site to native vegetation. This effort has been led by Museum Restoration Specialist, Dr. David Kriska, and has involved the aggressive treatment and removal of the Phragmites at the site, as well as the planting of native plant plugs and seed mixes to re-establish native vegetation. While the site may never return to the swamp forest it once was, the Museum envisions the 800-acre marsh basin returning to a rich diversity of native wetland plants including swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), and Greater bur-reed (Sparganium eurycarpum), among other species.

At the start of the restoration project at Mentor Marsh, the Museum did not own the entire marsh basin. This created a problem in that large swaths of the marsh were still under private ownership. Those areas would not have been able to be included in the Phragmites removal efforts. The Museum addressed this problem through a combination of land acquisitions and management agreements with private owners within the marsh that allowed for invasive species treatment of the entire Mentor Marsh basin.

In July 2018, the Museum purchased the 25-acre Fredebaugh Property in the southeast section of the marsh basin, a site that extended out in to the Mentor Marsh basin. This property purchase was funded through a grant from the State of Ohio’s Clean Ohio program. At the same time the Museum acquired a 20-acre conservation easement in the far-western section of the Marsh basin.

Consolidating the Museum’s land ownership of the marsh basin through such acquisitions is the best way to insure that the Museum is able to manage the site in the long-term. If isolated stands of invasive Phragmites are allowed to persist in the marsh basin, they will remain a seed source that will allow continued invasion in to the preserve.

The Windsor Woods Preserve

In August 2018, the Museum purchased an additional 572 acres of land at its Windsor Woods Preserve, creating a sprawling 643-acre preserve nestled in the heart of the Grand River lowlands region. This purchase was funded through two grants, one from the State’s Water Resource Restoration Sponsorship Program (WRRSP), and a second grant from the Ohio Public Works Commission through the Clean Ohio program. The WRRSP grant was utilized as matching funds towards the Clean Ohio grant. The Museum had worked to protect Windsor Woods for more than 10 years, and had engaged in discussions with various landowners over the years before finally sealing the deal this year.

The ‘lowlands’ region of the Grand River watershed is a wild place, where the Grand River and its many tributaries weave in great arcs within the flat valley. Historic meanders of the Grand River eventually transform in to ‘oxbow’ channel ponds, which provide outstanding breeding habitat for many amphibian species. The preserve is home to at least 11 different species of salamanders and frogs. Some of the old channels of the Grand River are now high-quality peat wetlands and the preserve harbors a population of the native wild calla (Calla palustris) that grows within one of these peat systems. Beavers have also exerted a heavy influence on the landscape at Windsor Woods. Through the building of dams, beavers have engineered expansive open water wetland areas, and have contributed to the habitat diversity at the site.

The Grand River frequently breaches its banks in this part of the Grand River lowlands which can lead to large sections of the preserve being temporarily inundated with flood waters, and can even necessitate the closing of certain roads in the area due to flooding. Visiting the preserve at different times of year can therefore provide very different landscape views.

Windsor Woods is also unique in that it is situated in a large block of land that is absent of any major roadways. The Museum’s preserve is located in the interior areas of this swamp forest block and is largely buffered from the influx of invasive species that often invade preserves from roadways. The Museum certainly envisions continued expansion of this preserve in the future if the opportunity should present itself.

The Minshall Alvar Preserve on Kelleys Island

The Cleveland Museum of Natural History has a long history of conservation work on Kelleys Island, located in the western basin of Lake Erie. The Museum has a total of nine nature preserves on Kelleys Island presently, including several preserves with frontage on Lake Erie. Kelleys Island is essentially a large limestone block in the middle of the lake, and it is home to many limestone-loving plant species that are not common in the Cleveland area, and are typically more prevalent in areas west of our region. The topsoil layer on Kelleys Island is very thin, with a limestone rock substrate very close to the surface.

The Museum has long considered the Minshall Alvar property, located in a less-developed area in the northwest corner of the Island to be an important conservation target. Through a partnership with the Trust for Public Land, the Museum finally acquired the Minshall Alvar Preserve in October 2018. The Trust for Public Land (TPL) and the Museum secured funding from the Clean Ohio Conservation fund to purchase the property. The Minshall family generously provided the matching funds that were needed to be eligible for Clean Ohio funding in the form of a bargain sale of the land. The site harbors two globally-rare snakes including the Fox Snake and the Globally-imperiled Lake Erie Water Snake. The preserve’s plant communities are very diverse. Wave-splash alvar wetlands are present along the Lake Erie shoreline at the preserve, and unique microhabitats are perched atop large limestone blocks on the shoreline. The rare mountain rice (Piptatherum racemosum) is among the unique plants that are found on these limestone blocks at the preserve.

The preserve also protects the most mature forest present on Kelleys Island, a noteworthy forest dominated by hackberry (Celtis occidentalis), blue ash (Fraxinus quadrangulata), and honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos). And the honey locust at the preserve are not the thornless cultivars that we are used to seeing in our gardens! They are fully-adorned with long painful thorns that can be both ornamental and agonizing to the touch.

The Minshall Alvar Preserve also contains a formerly quarried area in the center of the property that is home to the State-endangered lakeside daisy (Tetraneuris herbacea). The Kelleys Island State Nature Preserve is located next to the Museum’s Minshall Alvar Preserve, and the lakeside daisy was re-introduced to the State-owned property in 1995, and it subsequently naturalized and spread to the Minshall property over time. More than 200 individual lakeside daisy plants were counted by Museum staff on the Minshall property in 2017. Unique switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) meadows and even shallow buttonbush wetlands are also present in the former quarry area, creating a diverse matrix of different plant communities. And shrublands dominated by Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana) are also abundant at the preserve.

Conclusion

The Museum is actively growing its network of nature preserves in Northeast Ohio. Its focus is on expanding existing preserves, especially when it results in the protection of entire wetland systems or other natural features, or when additional acquisitions can be useful from a preserve management perspective. Anyone who is interested in learning more about the Museum’s conservation work is encouraged to sign up for a field trip through the Museum’s website, www.cmnh.org. Several trips to Museum preserves are offered every month.