by Elsa Johnson

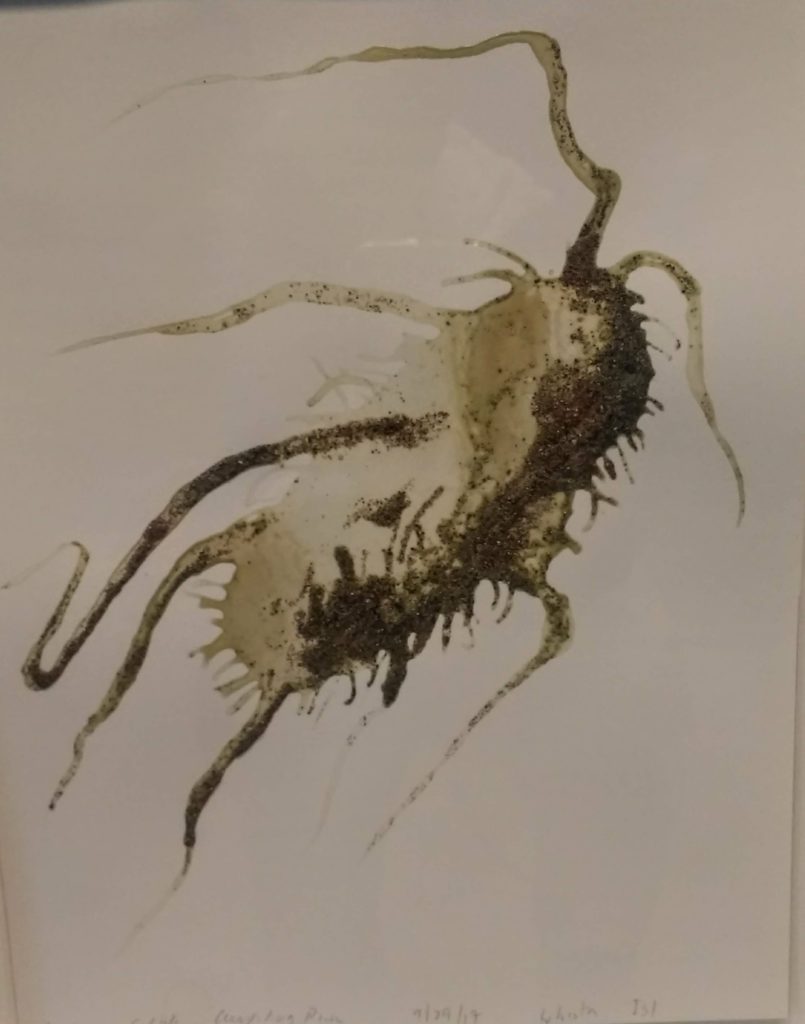

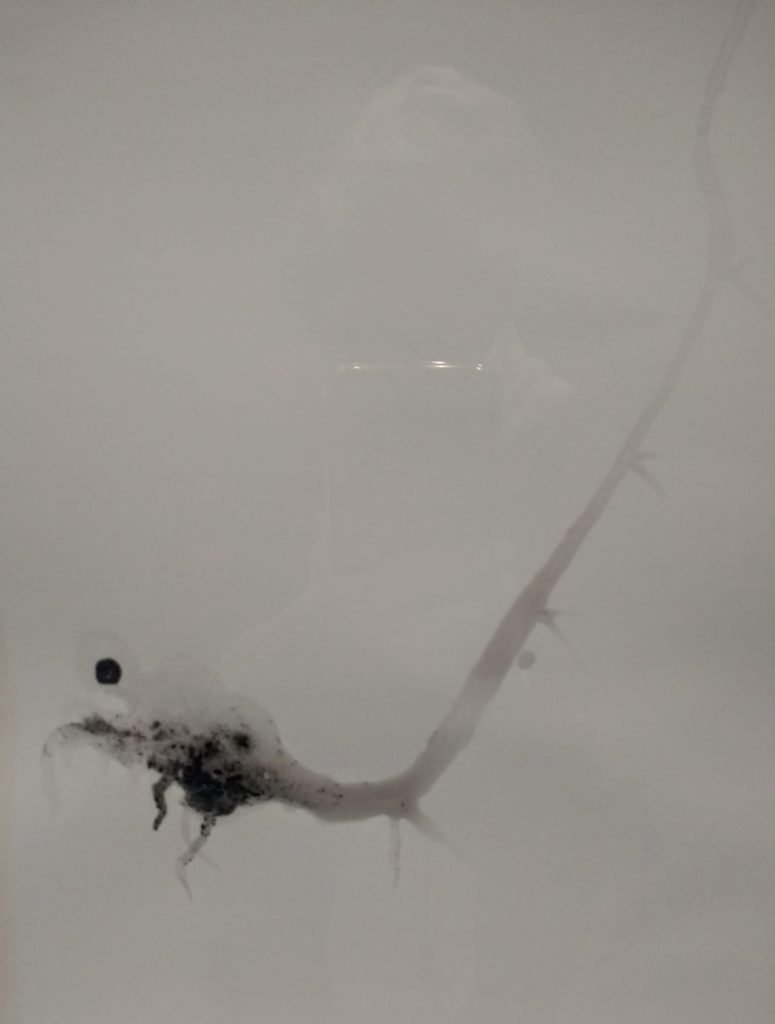

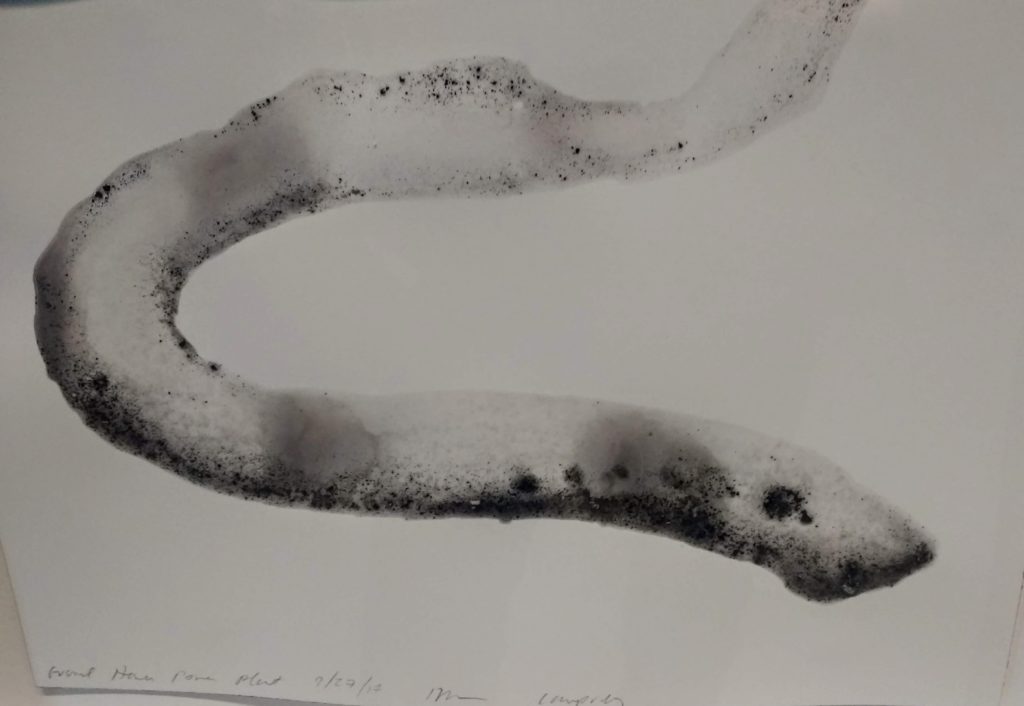

On Tuesday I spent an hour (not really enough time, but I had a meter running) at Cleveland’s Museum of Contemporary Art, free on election day (great idea there, MOCA). I wanted to see the current exhibit, The Great Lakes Cycle, by artist Alexis Rockman, who aligns environmental activism with art in a most satisfying way. The exhibit introduces itself through a collection of some of Rockman’s field ‘sketches’ – which are actually not sketches but black and white watercolor renderings with a delicious, ephemeral watery look –

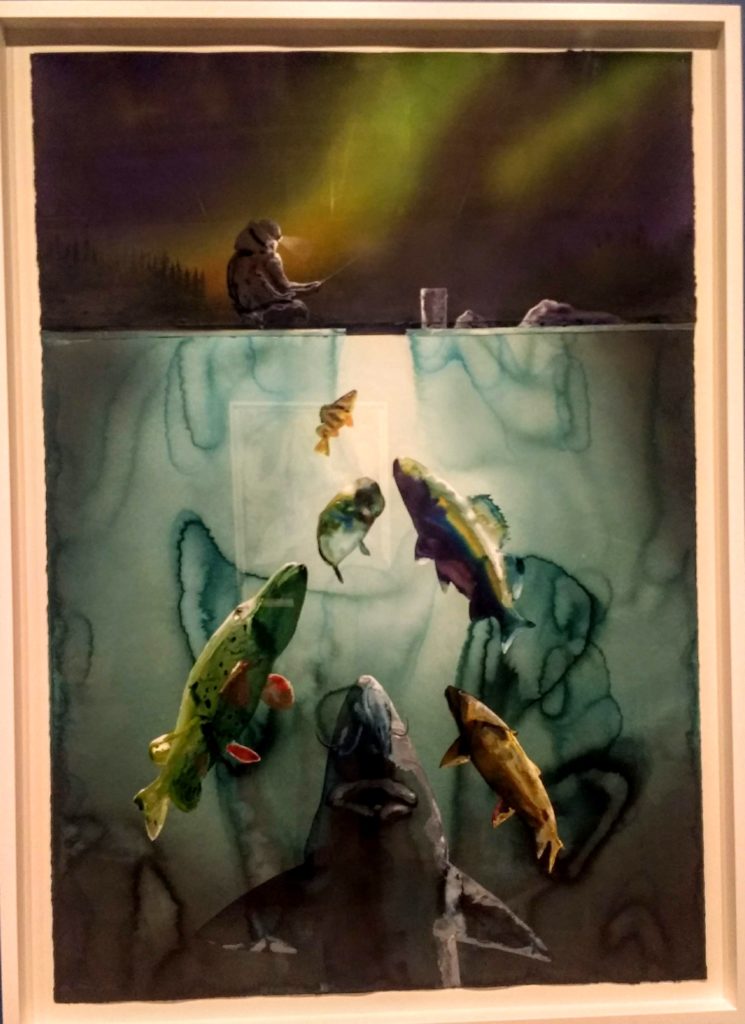

Following that, in the first exhibit hall, is a collection of large scale equally watery, equally delicious watercolor paintings that allow one to appreciate Rockman’s loose yet explicitly detail-suggestive handling/execution of this challenging medium.

Leading to the largest room, in which hang the five great paintings for which the exhibit is named. These fill-the-wall scale paintings are visually rich, emotionally affecting, and intellectually exhilarating, educating, and depressing. Don’t let that last keep you away. This is a must see exhibit.

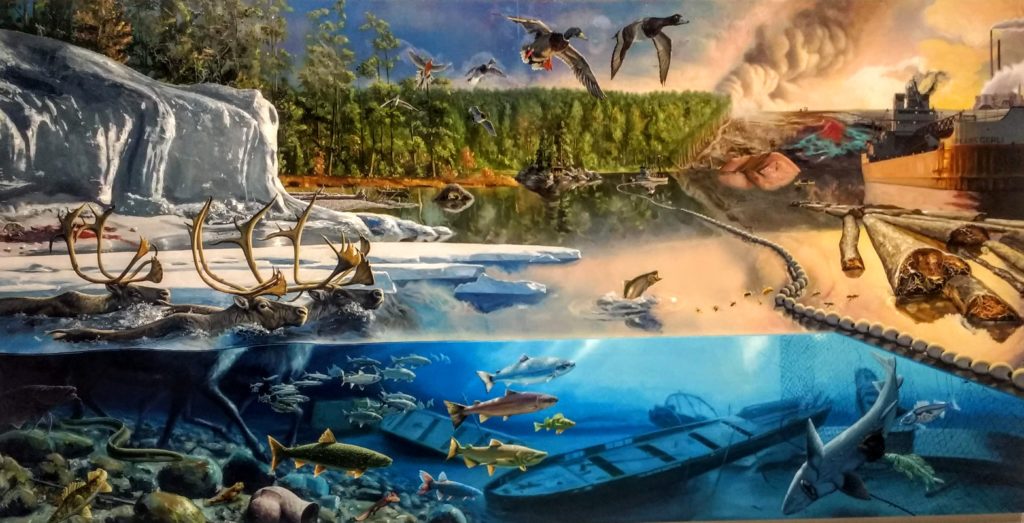

These five paintings are visual studies through a vast extended timeline of man’s interaction with and effect on the Great Lakes. One ‘reads’ the paintings from left to right, with the left side representing the original pristine natural environment.

In all the pictures the left side is the oldest in the timeline, and the timeline changes progressively through time toward the right side, which is the historically most recent and most ecologically disturbed, abused, and debased. That juxtaposition on one canvas, of those effects of which we are not unaware but often not thoughtful about, brings the alteration profoundly home. It is a slice through time and physical reality that shows us, both above and below the water, the changes wrought as it enumerates the natural, the unnatural, and in one painting the imaginary, denizens of the lake and shore. The paintings are a little overwhelming and deserve more study than a ticking meter allows.

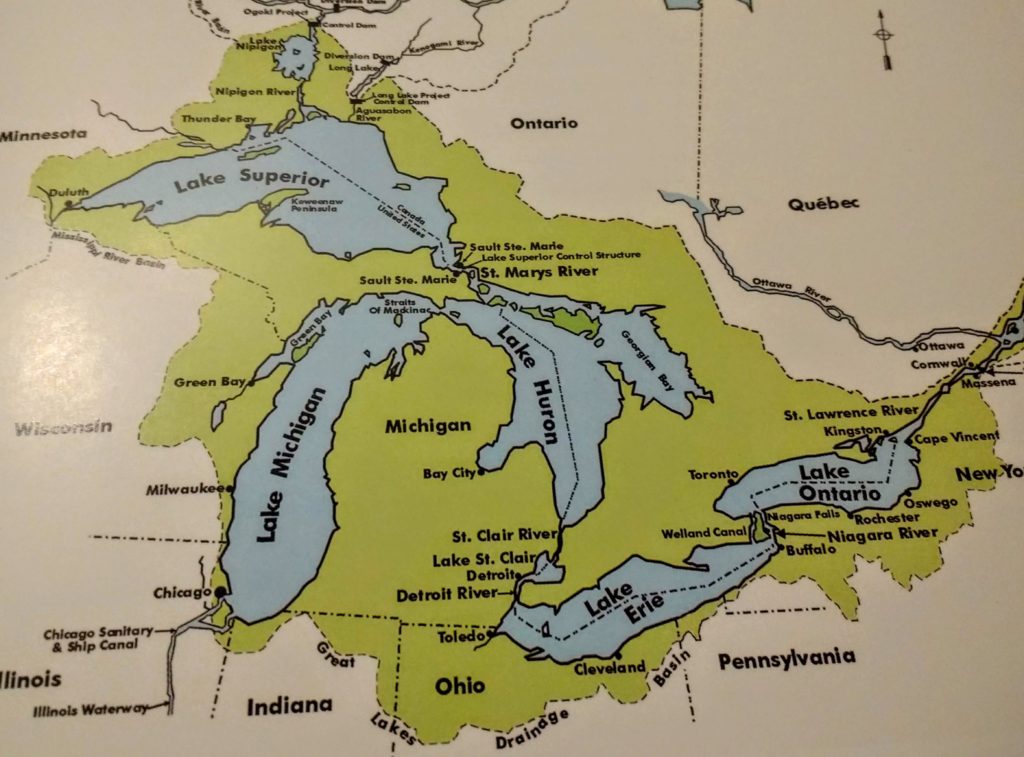

A little Great Lakes history here, cribbed from an accompanying book of the same title (available in the gift store): The Great Lakes were carved by glaciers over vast millenia of geologic time, and were equally slowly revealed as the glaciers receded. Better described as inland seas, they reached their current form roughly 5,000 years ago. They carry 18 to 20% of the surface freshwater on the planet. If combined into one, that sea would span the combined landmass of Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont. The Great Lakes hold 6 quadrillion gallons of water – enough to cover the continental United States with a layer of water 10 feet deep. The northernmost lake, Superior, is the world’s largest lake by volume of water, while Lake Erie, our canary-in-the-mine lake (my description, not the book’s) is the southernmost and shallowest. Lake Erie has the most productive fishery, and is the most quickly flushed (my choice of words, not the book’s – and believe me, fast flushing is a good thing). Surrounding the Great Lakes is a rich diversity of ecosystems.

There are 5 paintings. It is not really clear to me that each painting represents a specific lake. Rather, each painting addresses a common issue all the lakes have. The painting titled Pioneers, focuses on aquatic life, and the in-migration of aquatic life since the end of the last ice age, from the sturgeon that fed the first Native Americans to today’s aquatic invaders, shown as a stream of small creatures ejected from an anchored ships ballast water.

The painting titled Cascade is a study of man’s continuing impact on nature, a mix of human and natural history, from the elk swimming across the water on the left to the blighted industrial landscape pictured on the right, set off by buoys.

The painting titled Spheres of Influence explores how the interaction of the global ecosystem (weather, birds, insects, bats, and air-borne micro-contaminants) has shaped the current condition of the lakes

The painting Watershed illuminates the shift that happens as pristine streams and rivers are contaminated by modern agriculture and urban development. It’s pretty disturbing…

And finally, the picture Forces of Change illustrates these – both the past, and the potential future – complete with an imaginary e-coli kraken – if we continue on our current polluting ways.

A day following my trip to MOCA to see this exhibit I attended an evening panel symposium at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, discussing the state of our lake. What good timing I thought! I thought I could include a synopsis of that panel discussion here at the end of this article, but I have come to see that it is a separate article of its own. So I will end here with a synopsis of each lake’s problems as taken from the book:

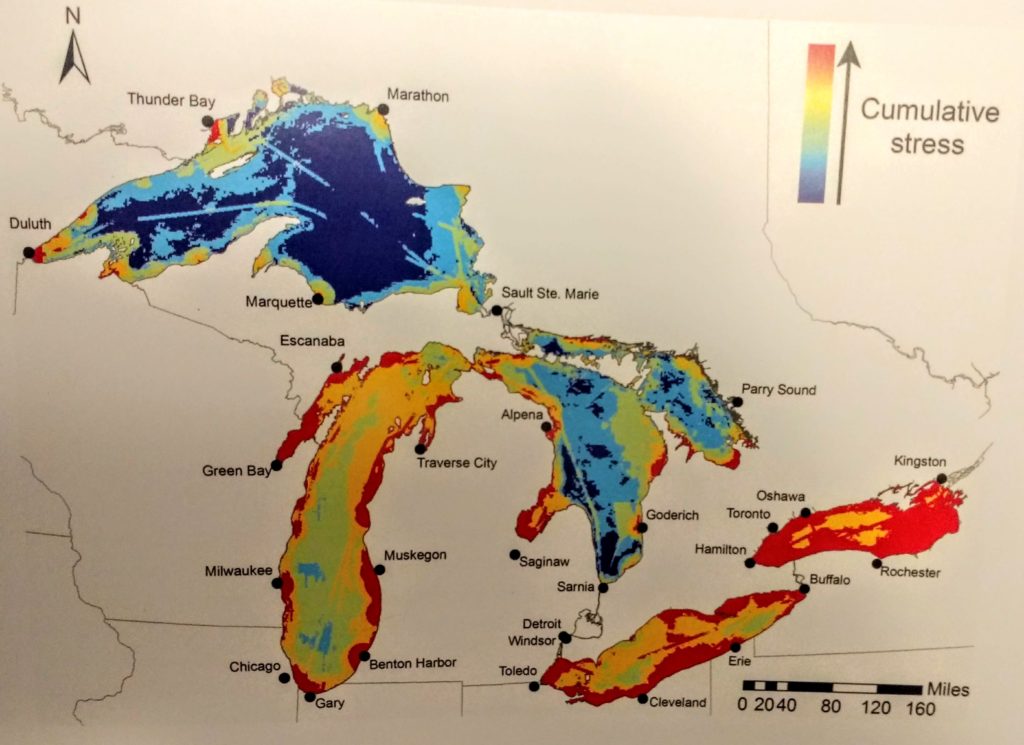

Lake Superior is the fastest warming large lake on the planet. Warmer waters threaten this lake’s cold water fishery. Lakes Michigan and Huron are essentially one lake; they have been invaded by zebra mussels, which filter immense quantities of plankton through their bodies. This gives the water clarity, but that clarity is indication of meager fish. Lake Erie suffers from toxic algae blooms, which are likely to double as the climate changes. And Lake Ontario suffers from being used as a toxic dumping ground, which are now locked into the lake’s bottom sediments. What follows is a map from the book showing cumulative stresses on the lake. It does not differ significantly from one projected on the screen at the museum talk, so I include it here:

I hope you will go see this exhibit and spend some time with it. Take the kids.