by Elsa Johnson

Community

Recently several of Gardenopolis’ editors traveled to the Toledo Museum of Art to see the installation by Rebecca Louise Law. Composed of a vast multitude of infinitesimally thin wires of natural and artificial materials hanging/descending from a two story ceiling, this was a magical experience, as the pictures show. Originally installed when most of the materials were fresh, by the next to last week of its run, when we saw it, the flowers, seed heads, and leaves were desiccated, but still entirely recognizable, and often still quite colorful. It was quiet inside the hall in which they hung. If people talked to each other, it was quietly, as if it would be wrong somehow to impose on what was a kind of meditation. There were subtleties to be enjoyed, such as the muted mysterious shadows of the plant materials reflected on the walls by the muted lighting.

Re-visiting Rockman

About a month or so ago we ran an article on the Alexis Rockman art exhibit at MOCA Cleveland: The Great Lakes Cycle (also now closed). That article spurred a query from one reader about why fertilizer contamination is currently a problem in the agricultural lands of northwestern Ohio. To whit: “I thought there were regulations in place.”

Around the same time that I visited the Rockman show, I also attended a panel discussion held at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History on Lake Erie. Two of the participants in particular spoke to this issue, Dr. Laura Johnson, Director of the National Center for Water Quality Research, Heidelberg University, and Dr. Jeff Reutter, former director of Ohio Sea Grant and Stone Lab. They were two of four panelists. The following is my attempt to corral their part of a discussion — that necessarily jumped about a good bit — into a single organized presentation. Any errors are entirely my own.

What we know: Our lake is a finite resource. It is the 13th largest lake in the world. It is the shallowest of the Great Lakes, and because of that, it is the most productive as a fishery. But this shallowness also makes it extremely vulnerable. The lives of 3,500 species are tied to the health of the lake. Many are now endangered. What happened?

We know that the highly productive farmlands of northwestern Ohio are the result of draining what once was called the Great Black Swamp, a formidable wetland monster that was tamed for agriculture by a system of underground drainage that carries water off the land into ditches, and thence into the natural watershed (primarily the Maumee River). We know that modern farming involves fertilizers, both natural and chemical, being applied to the land at the start of the growing season. But fertilizer doesn’t stay put. Inevitably some of it gets into the watershed. In the late 1960’s people realized the shallowest part of Lake Erie, the Western Basin, was, as a result, becoming a giant cesspool. Regulation followed, and, for a time, it was better. Around the year 2000, however, the quality of the water again took a turn for the worse. Here are two of the panel members explaining this.

Dr. Jeff Reuter: Mid 1990 to the present has seen an increase in dissolved phosphorus entering the lake, which is a form that is very easy for the harmful algae to use. In 2008, 3,800 tons of phosphorus entered Lake Erie from the Maumee watershed, the largest of Lake Erie’s tributary watersheds. To reduce phosphorus from agriculture entering Lake Erie, we are using a system of voluntary incentives and disincentives meaning that we are offering only carrots, not sticks. We are also seeing the impact of climate change, with more severe storms producing more run off. The system sets up a false dichotomy of farm economy against lake economy (that lake economy is valued at 14 billion dollars). We want both.

Dr. Laura Johnson: It does not take a lot of phosphorus in the warm shallow waters of the western basin to cause a nuisance problem…. i.e., a lot of farms, leaking a little bit. Most farmers now apply at recommended rates and data suggests that application of phosphorus and removal via crops is largely in balance. The best reasoning for the losses is that phosphorus application on the soil surface associated with broadcasting in the fall combined with the massive system of subsurface tile drainage is allowing for excess dissolved phosphorus loss. Thus efforts should be focused on nutrient management- that is applying phosphorus at the right rate, time, and place. For instance, some studies suggest inject phosphorus fertilizer deeper than 2 inches in the soil could reduce losses by 60%. However, there needs to be more incentives to provide the appropriate technology to farmers to increase the use of this practice.

We’ve had some extremely large blooms since 2008, some of which were very toxic. The toxin produced by these cyanobacteria, Microcystin, is more toxic than cyanide. Although these toxins are filtered out at the drinking water treatment facility, the costs have increased drastically and can be over $10,000 a day in Toledo during bad blooms years. The high level of toxins entering this plants could get to a point where it overwhelms filtering capabilities. At the present time the western basin is the most affected, but the blooms in the western basin move over to the central basin threatening water intakes there as well. The central basin also has different blooms that prove challenging for the region. Clevelanders will be relieved to know that, unlike Toledo, Cleveland has multiple water intakes, thus, Cleveland’s water supply is not as vulnerable.

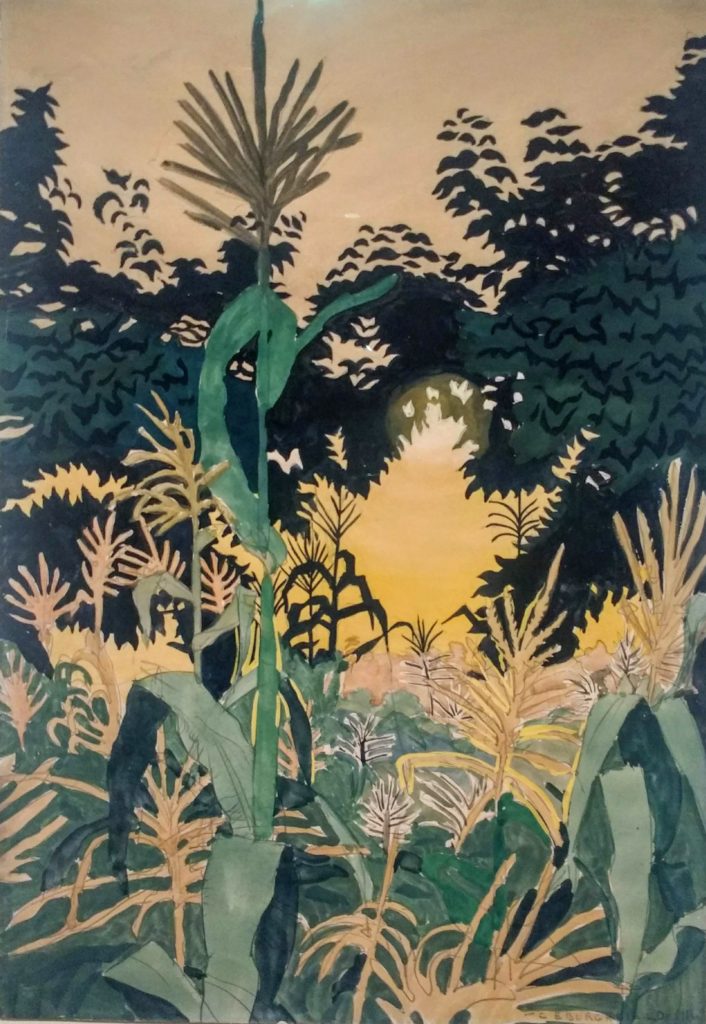

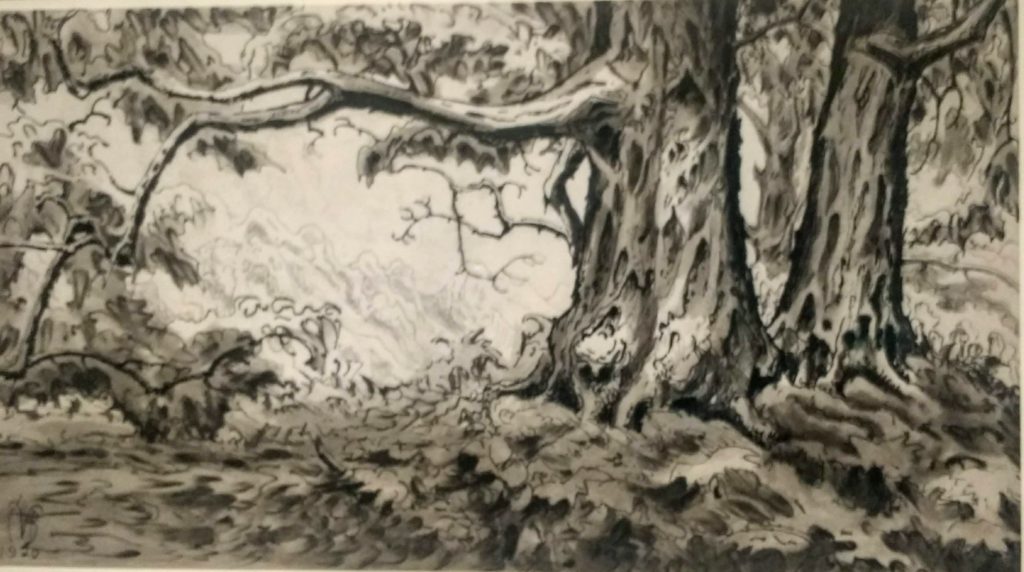

An artist of our own

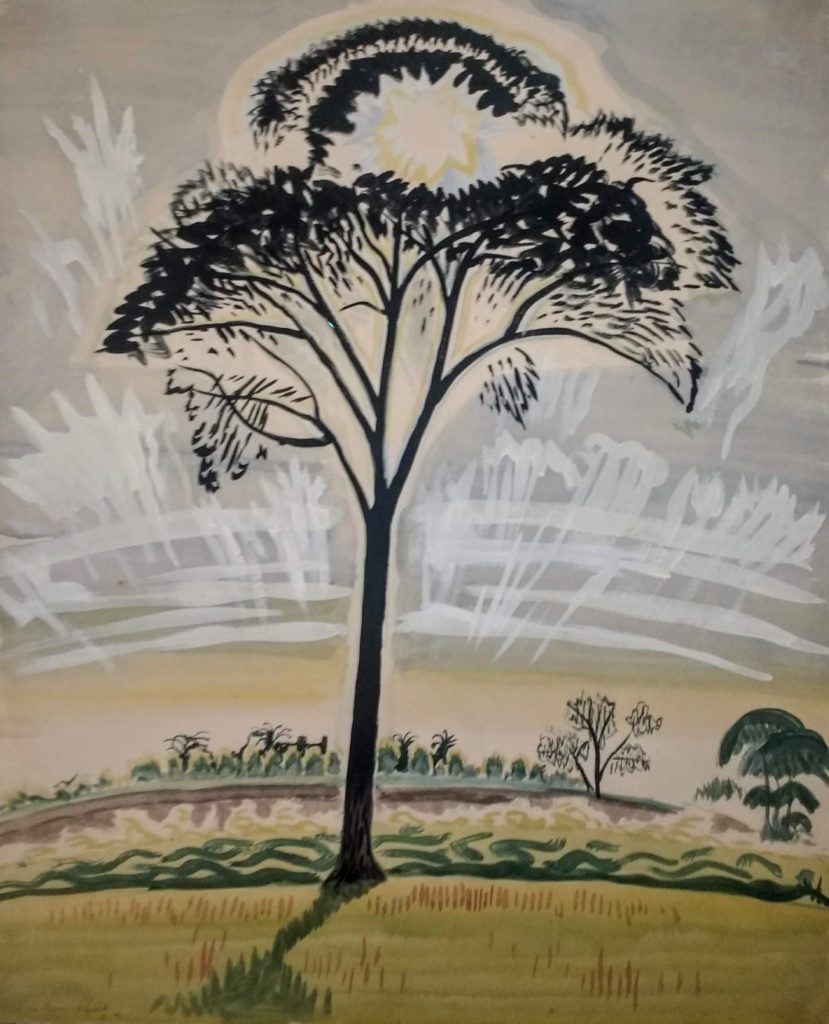

The artist Charles Burchfield was born in Ashtabula Harbor (I am taking this from explanatory material from the exhibit – and I don’t know about you, but upon reading this I found myself hoping he wasn’t literally born in Ashtabula Harbor), and studied at The Cleveland School of Art (now CIA). After WWI he returned to northeast Ohio. Burchfield, like Rockman, was a watercolorist, but to a very different purpose. Both are representational painters, but where Rockman uses his considerable skill to create hyper-realistic paintings that are muralistic, that tell a story of environmental purity and degradation over time, Burchfield used color and form in small paintings that express personal emotion and mood through landscape. For example, in the picture of the tree with the branches reaching up to a glowing sun, Burchfield suggests the divine influence he saw in nature.

In another painting, the accompanying sign explains, an orange stream divides an area of barren yellow from an area of lush green, suggesting the impact of mining – often abandoned after the resource had been depleted — on the eastern Ohio landscape.

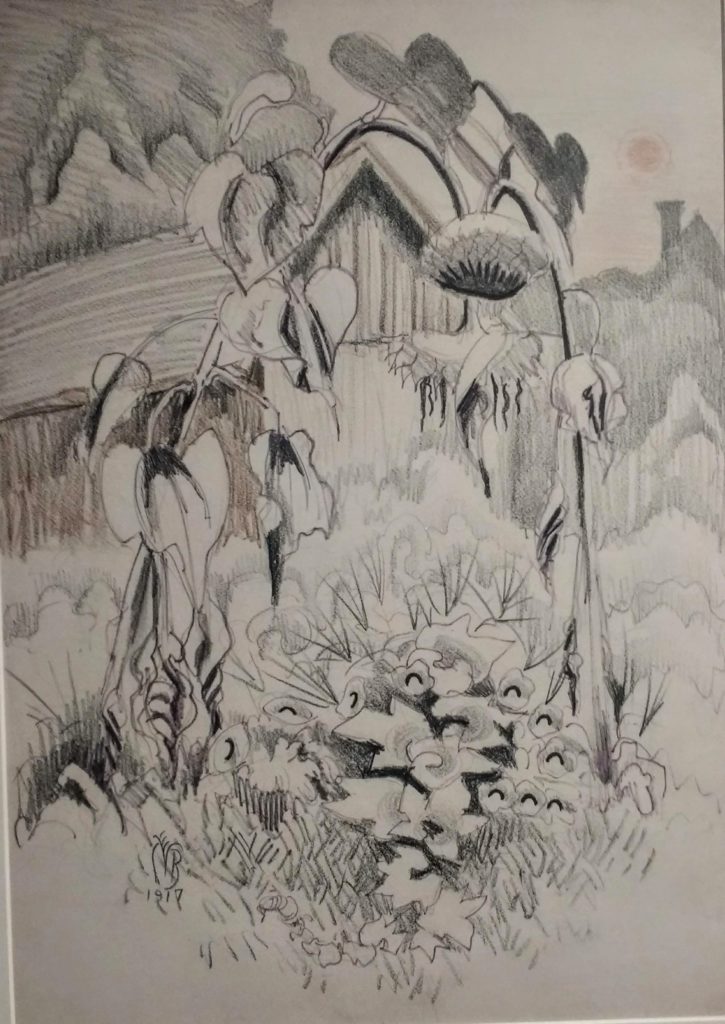

Even Burchfield’s pencil drawing of a chestnut tree, while explicitly representational, seems deeply imbued with mood.

The Burchfield exhibit is current and can be found in the small gallery opposite the gift shop at the Cleveland Museum of Art. A reminder for seniors: if you are a member, parking is free on Tuesdays.