By Elsa Johnson

Here I am, sitting on my front porch on a sunny mid-September day, watching the Monarchs drift from buddleia blossom to blossom while listening to a Davey Tree Company crew two doors down the street cutting down and removing 3 huge old black locust trees that all lost their heads in that microburst/possible small tornado mid-summer. This is an older neighborhood, with most houses almost one hundred years old, which means there are an unusual number of unusually old and unusually tall black locusts which that storm unusually affected (one wonders, why did the black locusts, in particular, suffer so much breakage?).

But it must be observed that, of the trees in my neighborhood, which borders a small park, the black locusts (those that didn’t get damaged) are looking good – fresh green, and healthy – despite a difficult summer of heat and drought. The same cannot be said of many of the other trees on this street, which are mostly ash and maple, with a couple horse chestnut trees at either end. The ash, of course, are succumbing to Emerald Ash Borer – and the horse chestnuts always tend to look a bit sorry by summer’s end, but to what are the maples succumbing? On my very short street (7 houses on one side of the street, 7 on the other, for a total of 14 houses) one maple was uprooted by the storm, but half of it was dead already, and of the three maples directly across the street from my house, two of them have many dead or dying branches in their upper canopy – with a bit more dying each year, for the past several years.

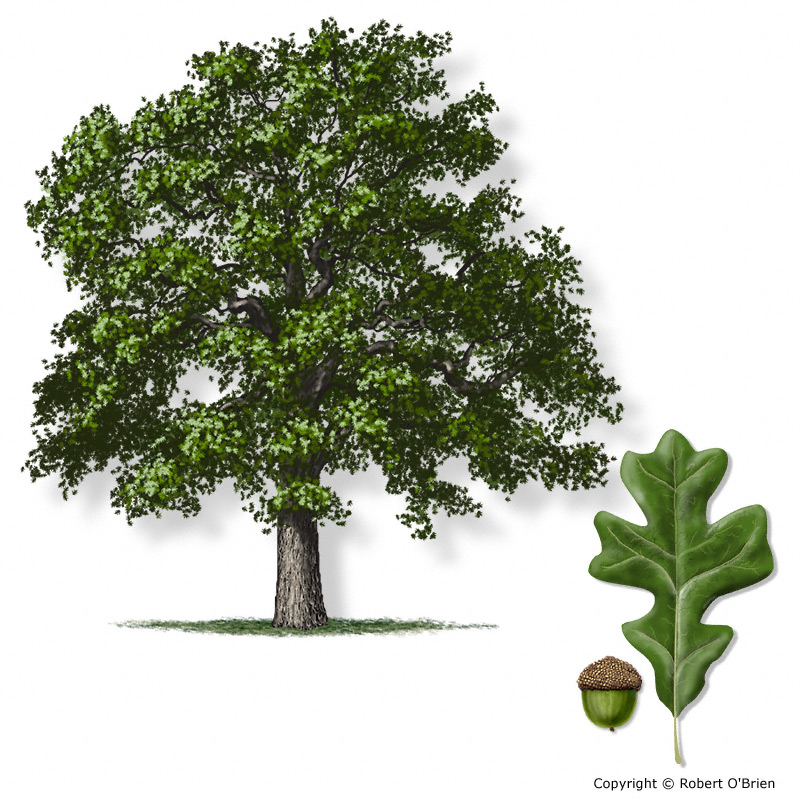

In another Cleveland Heights Neighborhood a friend has pointed out an area where many large, old oaks have recently died and been removed, and where others are looking not so good. Then there are the dead and dying large old oaks in certain areas of Forest Hill Park (and now a specimen beech, too).

What’s going on?

So I was particularly interested in Louis Iverson’s presentation on the U.S. Forest Service’s Climate Change Tree Atlas, when he spoke recently at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History’s 2016 symposium Nature on the Edge. And what a useful tool this is! Using computer modeling, projections have been made for individual tree species’ survival and ability to cope or thrive in best cast and worse case scenarios under climate change by 2100.

This tool is useful in two ways. The first, by helping us to diagnose and understand what is going on around us now – and the second, by helping us make wise decisions in both the public and private spheres concerning tree choices that will survive and adapt to a changed and ever changing climate here in northeast Ohio.

Climate change will not be leisurely, as measured by a tree’s life, with lots of time for tree species to adapt, so maybe what we are seeing now, already, are the first signs of lack of adaptability of certain tree species. And while it may be heresy to some, perhaps instead of seeking to restore species traditional to northeastern Ohio’s forested ecosystems, we should be introducing trees that currently thrive in climatological habitats several climate zones further south. For what the worst case climate change scenario forecasts for us in 2100 is a summer much like the one we just went through, with fierce storms, extreme downpours, and prolonged periods of heat and drought – only all of it, in the worst case scenario, even more so.

It would be nice if we had time to explore, via research, the possible negative ramifications of such introductions, including the possibility of hitchhiking pests; a tree’s invasiveness potential; and possible disruption to synecological relationships (yeah – I had to look that one up, too), from fungi, to pollinators, to dispersal agents, but in the life of an ecosystem, or most northeast Ohio hardwood trees, 100 years is a short time, where, for us, it is more than a lifetime. Once those old tree are gone and there is no one left to remember them, it will be as if they never existed – things we would try to imagine, like passenger pigeons darkening the sky in vast numbers. There is no turning the clock back.

So what can we learn from the Climate Change Tree Atlas for NE Ohio? The chart lists 70 trees that currently grow in NE Ohio and examines each species for vulnerability and/or adaptability to change, then predicts which trees should show increase, decrease or no change, according to the model. Thus, by 2100, the chart says we can expect to see a decrease in black cherry, white ash, American basswood, swamp white oak, eastern hemlock, eastern white pine, and black ash (there are a few more – I selected those with which we are most familiar). These tree all are rated as having VERY POOR POTENTIAL to survive and thrive under worse scenario climate change. Listed as having POOR POTENTIAL are sugar maple, American elm, pin oak, and black maple. Gee – that’s a lot of the trees we commonly find around here.

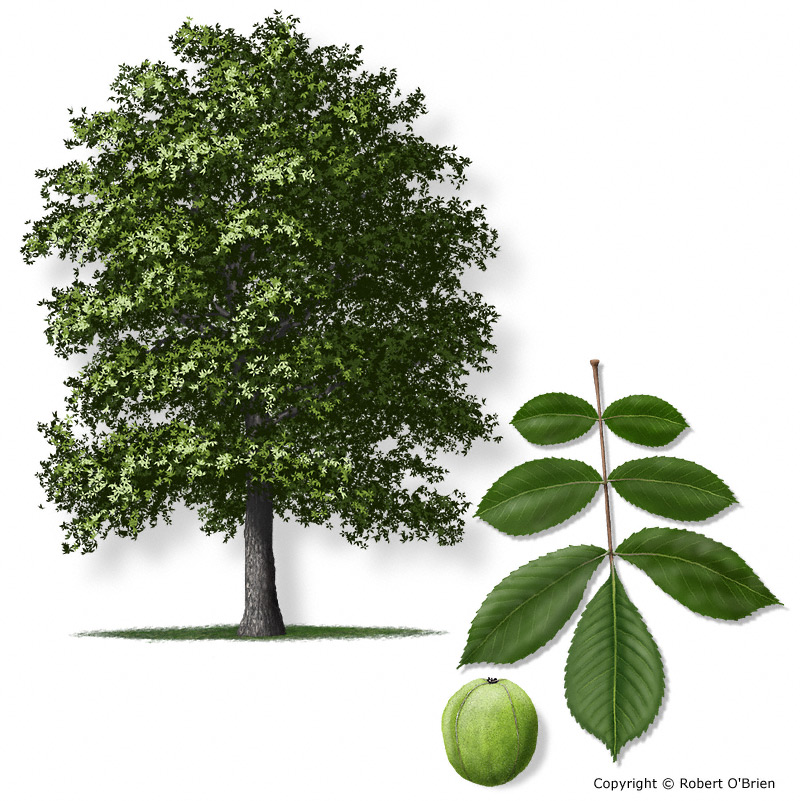

And what present tree species can we expect to have good potential? Osage orange, black oak, honeylocust, burr oak, butternut hickory, scarlet oak, and hackberry all have VERY GOOD POTENTIAL to survive and thrive. Also with GOOD POTENTIAL are black walnut, sassafras, eastern cottonwood, shagbark hickory, sycamore, cucumber tree, and shingle oak. These trees are already present here, and would be expected to cope with climate change and increase their numbers/habitat.

Some other existing species numbers in 2100 are predicted to REMAIN ABOUT THE SAME, according to the chart. This group includes red maple, northern red oak, slippery elm, eastern hop hornbeam, pignut hickory, black locust, black willow, Ohio buckeye, and serviceberry.

The chart also includes a list of trees that do not presently grow here but which are adaptable to what this climate will likely be in 2100, and these are on a list on the chart labeled NEW HABITAT. These are the trees that one might consider introducing: chestnut oak, Eastern redbud, Eastern red cedar, Northern white cedar, chinkapin oak, black hickory, blackjack oak, common persimmon, post oak, shortleaf pine, shumard oak, southern red oak, sugarberry, sweetgum, and winged elm.

Common Persimmon

Thuga

Post Oak

Swamp Chestnut Oak

Black Hickory

Blackjack Oak

Interestingly, most of the pictures I found for these trees came from a data base from Texas. Most of these tree are common to Texas, which tells you what worst case climate change may look like here in northeast Ohio in 100 years. And here I leave you – with a lot to think about.