By Diana Sette

For this issue’s Skills & Practices, we will look at ways to design for the anticipation of heavy rainfall extremes. We know that with climate change, we are and will continue to be facing more and more erratic weather patterns that overload current infrastructure. The more we can create built systems to function like wetlands, marshes, and prairies – among other systems that naturally handle occasional flooding– the more resilient we will be because we will be creating systems that work to, as Brock Dolman of the WATER Institute1 says, “slow it, spread it, sink it” rather than “pave it, pipe it, pollute it.”

For the purposes of this article, we will look at two design patterns that can be resilient when facing water extremes. Part One focuses on Rain Gardens, and the Part Two looks at how urban trees can work to manage water extremes.

Part I: RAIN GARDENS

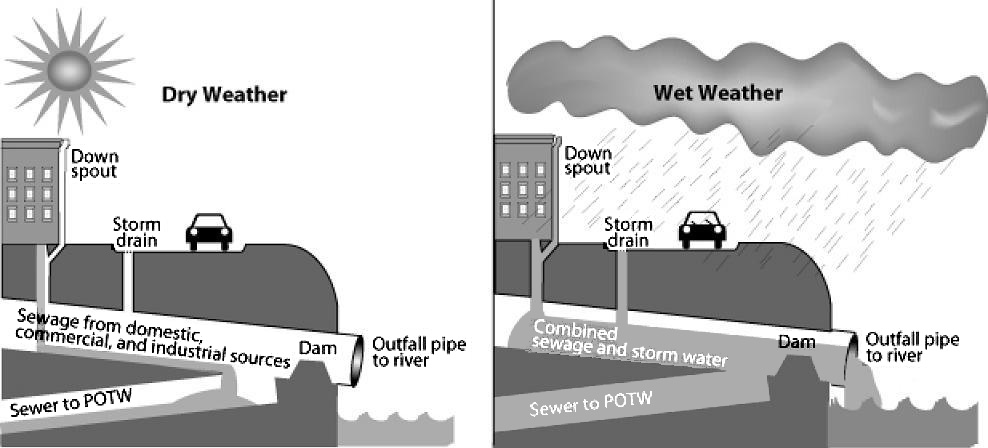

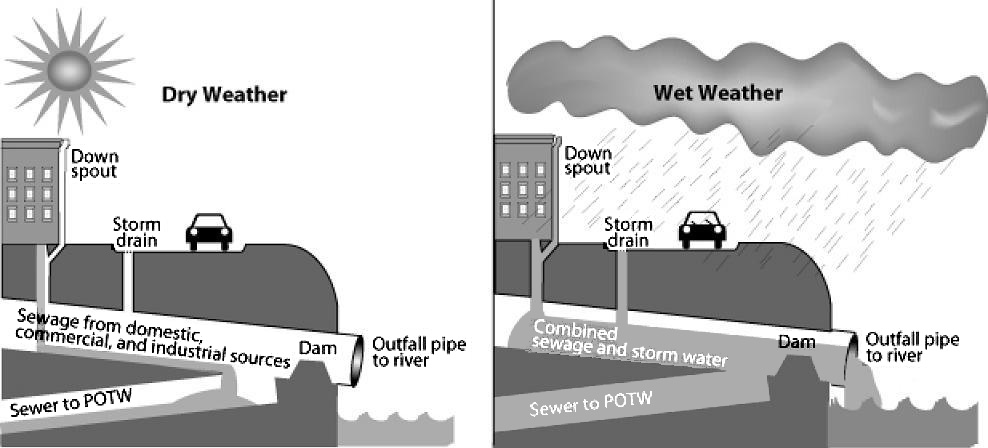

I am within biking distance from the beaches of Lake Erie. Lake Erie is the twelfth biggest fresh water lake in the world, and provides drinking water for over 11 million people.2 I regularly contemplate what happens to the Lake and its waterways when it rains. The prompting of this consideration does not take much, as one heavy rainfall causes the beaches to be closed for swimming due to unsafe levels of E. coli. This is because during extreme rainfalls, the stormwater overflows the water infrastructure system and puts stress on the streams resulting in the pollution of Lake Erie. The more that this region experiences heavy rainfalls3, the more this region will experience unsafe water management. This is because the City of Cleveland’s water infrastructure is set up as a Combined Sewage Overflow (CSO) system. CSO is a common system for many older cities that allows unfiltered and untreated sewage mixed with stormwater into the waterways when there is flash flooding that adds more water to the system for which it was designed.

While re-designing cities on a massive scale to integrate green infrastructure may be the end game, we can and must take action now to make small changes that manage stormwater on-site with what resources we have available to reduce combined sewer overflow, and reduce the storm water that is draining into our waterways unfiltered and unharnessed.

Sustainable urban drainage systems (known as SUDS in the UK) or low impact development (known as LID in the US/Canada) include the following techniques: permeable surfaces, green roofs, rainwater and graywater harvesting, and finally installing bioretention systems also known as rain gardens. For the purpose of this article, we will focus on rain gardens.

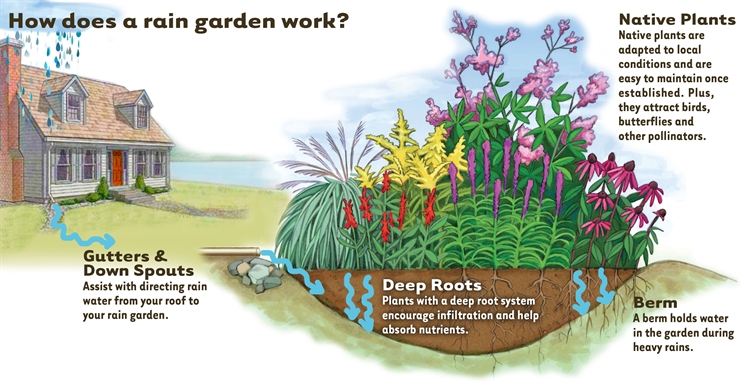

As permaculture designers, creating systems that require the least amount of input with the greatest output is one of the goals. One of the ways in which designers accomplish this is by ‘stacking functions,’ or rather, using something for multiple purposes as to get more ‘bang for your buck’ sort of speak. Designing a rain garden is a great opportunity to practice stacking functions. One function an effectively designed Rain Garden can be is to create wildlife habitat and increase biodiversity by increasing the food source and nesting area for pollinators and beneficial species. Depending on the plant selection, rain gardens can also add significant edible and medicinal value to the landscape. Rain gardens can also be places of solace and tremendous beauty. Most importantly for considering water extremes, rain gardens work to capture, store and filter water on-site, which in turn alleviates stress on waterways, recharges aquifers, reduces erosion, and reduces pollution to our drinking water.

But before we get to stacking functions in our design, let’s talk about the basics of rain garden design.

KEY STEPS to SUCCESSFUL RAIN GARDEN DESIGN

First: Choose a site. Choosing the right location for the rain garden is key.

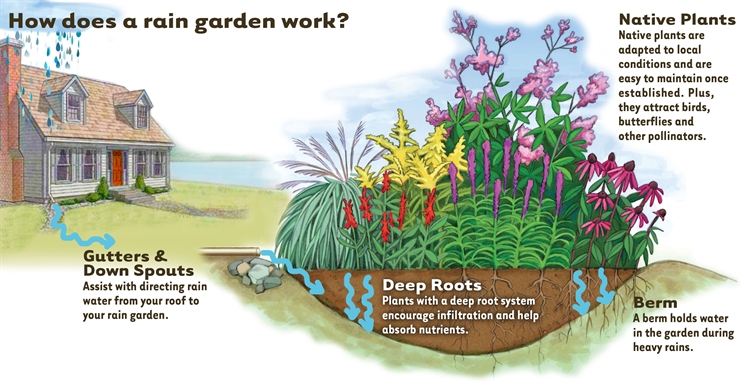

To start, rain gardens must be a minimum of 10 feet from a building to prevent any damage from overflow during heavy rainfalls. Rain gardens work well when they catch and filter stormwater runoff from permeable surfaces like roofs or parking lots, so placing a rain garden in juxtaposition to a paved surface is a wise consideration.

Secondly, rain gardens should be placed in locations with good drainage (not areas where water tends to pool). A rain garden can allow the land to soak up about 30% more than a patch of lawn!4 That being said, rain gardens are not a solution to wet areas in a lawn, nor should they be placed near the drain field of a septic system.

Second: Design the garden.

Deciding on the size of the garden depends very much on the amount of anticipated runoff from the roof and/or lawn that the rain garden that will flow into the rain garden. Ideally, a rain garden will be able to absorb all of the stormwater that drains away from the site.

If you are connecting a rain garden to the downspouts of your home, you can calculate the amount of rainwater using the following steps. First, figure out the footprint of your home by taking the length of the building multiplied by the width of the building. This will give you the square feet of your home footprint. Then count the number of downspouts on that building. Divide the square feet of your home footprint by the number of downspouts directed to the rain garden, and you will have the square feet of the roof area draining to the garden.

If you are placing your rain garden more than 30 feet from a downspout and using a rain garden to manage stormwater from an impermeable surface like lawn turf, driveway, or parking lot, you can calculate the amount of rainwater that will drain to the rain garden using the following steps. Measure the length of the uphill lawn area and multiply it by the width of the uphill lawn area. This will give you the square feet of impermeable surface that will drain into the rain garden.

If your rain garden will be managing runoff from both your house and lawn/parking lot, add those two total square feet together to get the total drainage area. The general ratio of drainage area to rain garden is 5:1 for a well drained, sandy soil profile. For example, if you had 500 square feet of drainage area, you would build a 100 square foot rain garden5. Then again if your rain garden site’s soil is compacted, poorly drained or clay soil, use a 2:1 ratio. It is also possible to excavate soil and replace with layers of compost and mulch to improve soil porosity. Many landscaping companies even offer ‘rain garden soil mixes’ now.

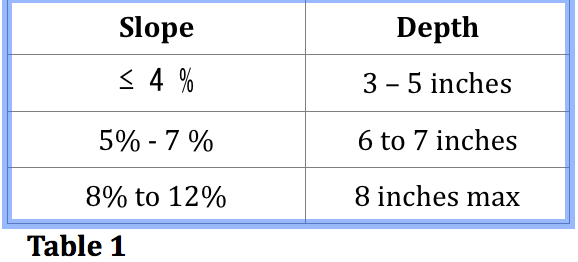

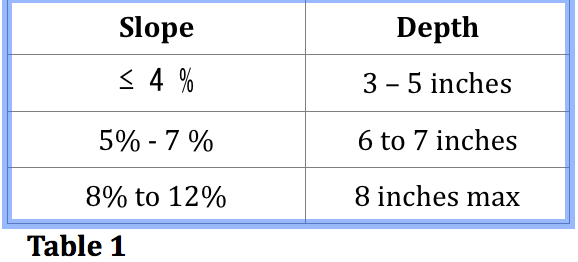

Also, it is important to consider the slope of where you want the garden to be. The ideal slope for a rain garden is between 3% and 8%. A general rule is that the steeper the slope the more work it will be to level out the area to create a flat basin. That being said, in general a slope over 12% are generally not suitable for rain gardens, as they require a depth for the rain garden depth above 8 inches, meaning that it might hold water for too long. You can use Table 1 below to determine the depth of your rain garden.

Table 1

The shape of a rain garden. Shapes vary with design aesthetics, but they tend to be in the kidney shape, as it allows for the natural container of water in-flow and storing of the wide brim. A solid berm is carved out and reinforced on the downhill of the rain garden to allow for water holding. This is one area that will be important to monitor over time, and do any maintenance work if needed.

Third: Get to work!

Before you starting digging, it is useful to call the “Call before you Dig!” hotline to make sure you are digging in a safe place. In the US. You can call 811, or go to call811.com to find out the direct state line to “call before you dig.”

Finally, invite friends and neighbors, and get a group together to help! Nothing builds community like collective work. What a great way to share knowledge and give purpose to a gathering!

A NOTE ON SPECIES SELECTION

A common requirement for all rain garden plant species is that they must be able to tolerate periodic flooding. From there, you can choose plants based on their needs for sun versus shade, and what is available at your site. Sun and partial sun for rain garden sites is best, though shade gardens are possible as well.

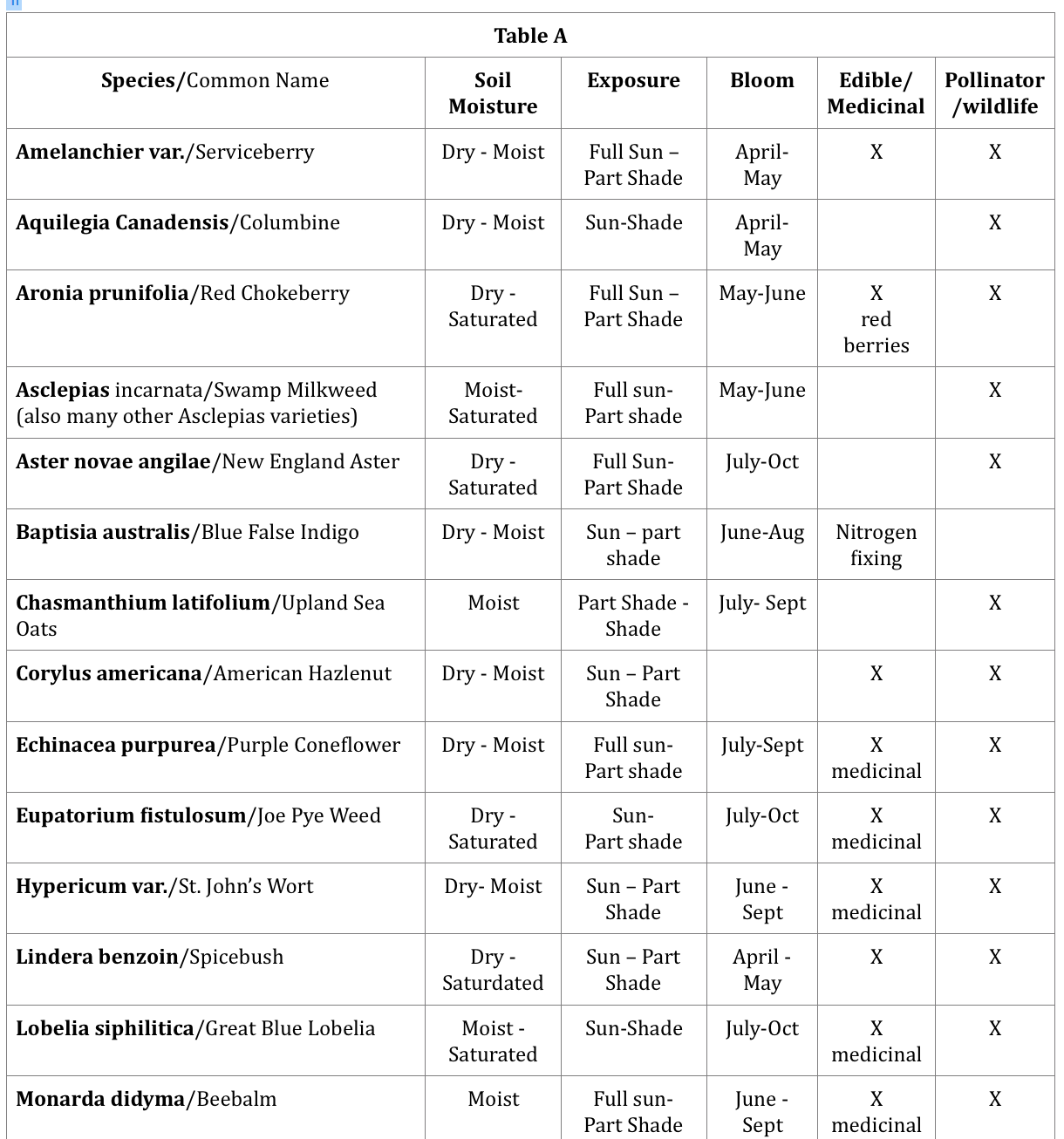

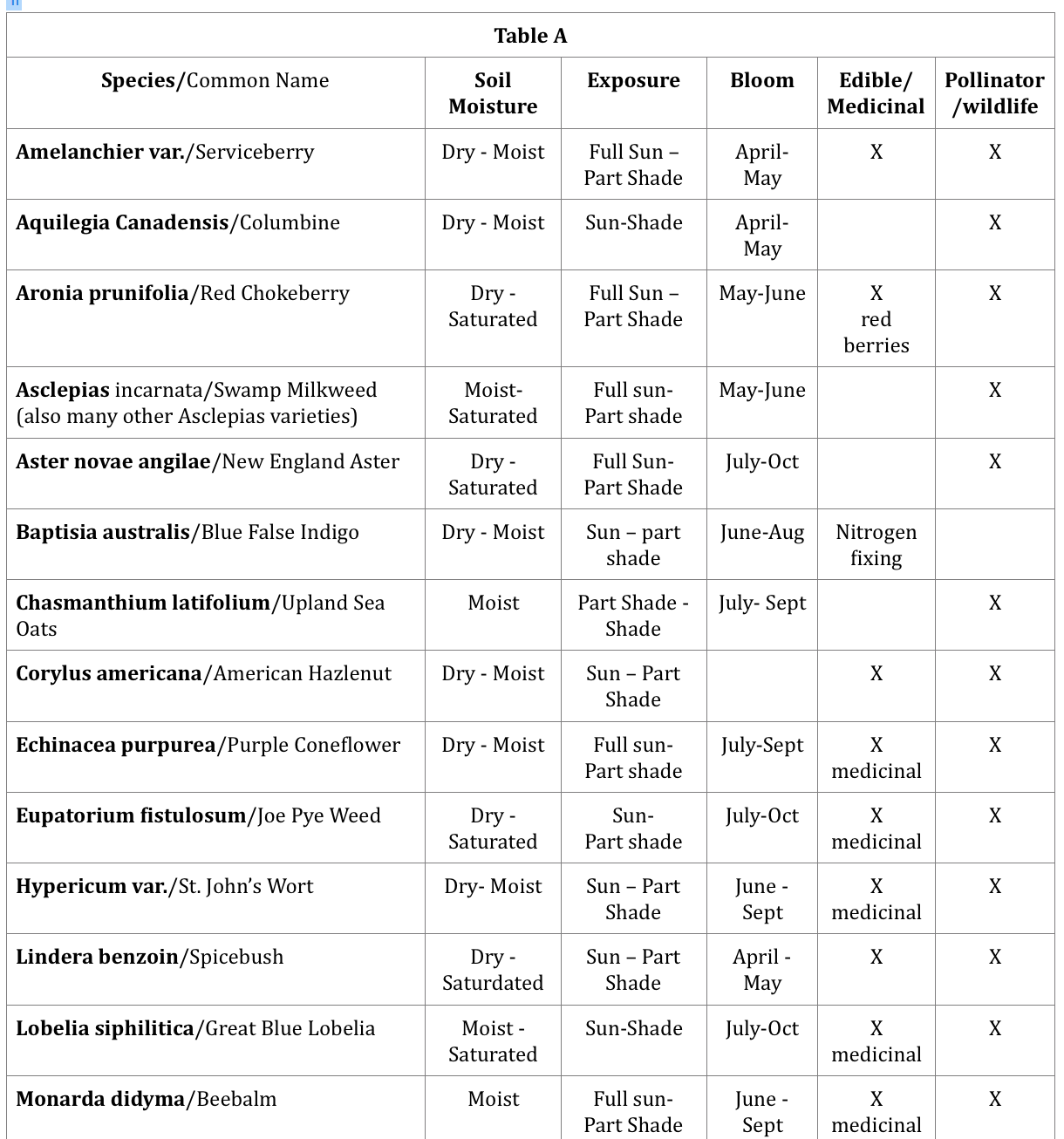

In order to optimize benefits of the rain garden, it is useful to plant perennial native species that tend to thrive in your region. With particular attention to their zone and soil moisture tolerance, you can find a broad range of color that can bloom from first to last frost. Currently working in a cool temperate moist forest climate, with some anticipation for the climate to be shifting towards a warmer temperate moist forest area, Table A lists some of my favorite herbaceous and shrub species for rain gardens. Listed in the footnotes are resources for plant selections for rain gardens in other climates6.

END NOTES:

1 The WATER Institue (Watershed Advocacy, Training, Education and Research) is a project of the Occidental Arts & Ecology Center in Occidental, CA. www.oaecwater.org. See Brock Dolman’s article “Watershed Relationships” In the Winter 2010-11 issue of Permaculture Activist # 78 for a more in-depth discussion and explanation of watersheds.

2. http://www.lakeeriewaterkeeper.org/lake-erie/facts/

3. Research of Cleveland climate patterns shows a 25.8% increase in annual precipitation from 1956-2012 with a 57.4% increase in precipitation in the months of Sept – November. Rajkovich, Nicholas B. “Climate Change and Cleveland” presentation, University at Buffalo. 2015.

4. Cornell Cooperative Extension. Introduction to Rain Gardens. http://hightstownborough.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/NJ-Raingarden-tri-fold.pdf

5. There is also a guide chart for assessing proper rain garden in Cornell University Cooperative Extensions “Installing a Rain Garden” manual. http://www.townofglenville.org/Public_Documents/GlenvilleNY_stormwater/01238879-000F8513.6/Installing%20A%20Rain%20Garden%20Cornell%20University%20Cooperative%20Ext.pdf

More worksheets available at Rain Garden Manual for Homeowners: Protecting Our Water, One Yard at a Time. Geauga Soil and Water Conservation District/Northeast Ohio Public Involvement Public Education Committee (NEO PIPE), 2006. http://www.clevelandwpc.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/raingarden_manual_forhomeowners.pdf

6. Brad Lancaster’s “Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond” website provides numerous useful rain garden plant lists for Dryland Regions (especially considering AZ, CA, CO, MN, NM, UT, WY climates) http://www.harvestingrainwater.com/plant-lists-resources/multi-use-rain-garden-plant-lists/ The “Rain Gardens for Nashville” Resource Guide provides a thorough species list with particular attention to Southern US region climate. https://ag.tennessee.edu/tnyards/Documents/Rain%20Garden%20Brochure%20Metro%20Nashville.pdf Many of the other Rain Garden Manuals cited in the End Notes provide plant recommendations as well. Numerous seed companies are selling ‘rain garden seed mixes’ as well. See Prairie Nursery, Ohio Prairie Nursery, Prairie Moon Nursery, Roundstone Native Seed, Ernst Seeds, The Vermont Wildflower Farm, among many more you can find online.

Other Useful Resources for Rain Garden Design Inspiration…

Part Two: Urban Trees

The industrialized “pave and pipe paradigm” is “disastrously flawed and hydro-illerate”1.

Many cities are completely paved and piped with little to no green space, or daylighted rives, creeks, or streams. On the other hand, some of the most enjoyable spaces in a city are where there are urban trees thriving. The temperature is cooler, people tend to feel more relaxed in the environment, and interestingly the density of tree canopy is reflected in income levels as well.2 Cleveland, OH, historically known as “The Forest City” has lost about 100,000 public trees since 19403.. Some now call it “The Deforest City,” though many people and organizations are working to make it “The Reforest City.” The efforts to plant more urban trees is for many reason, one being that the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District based in Cleveland is under a federal order (aka a consent decree) to reduce the volume of sewage that overflows into the local waterways due to gross amounts of water pollution. By focusing on the replanting of urban forest canopy, significant steps can be taken to improve water quality and restore the local hydrology.

“Cleveland’s urban forest intercepts an impressive 1.8 billion gallons of rainwater every year, a service valued at just under $11 million”4. With the increased frequency of water extremes in this region, we can plan to see more and more rainfall, and urban trees that are well-planted and cared for present a significant design solution to managing water extremes in a resilient way.

Trees & Stormwater Management

Trees have numerous benefits in stormwater management including: runoff absorption, water filtration, erosion prevention, recharging aquifers, reducing impermeable surfaces like compacted soil through root growth, and helping control water temperatures that may otherwise lead to high temperature waters prone to algal bloom.

For a minute, imagine rain as it falls from the sky. If the ground is bare or paved, the raindrops hit the ground hard, bounce off and head downhill as fast as possible. However, if the rain falls on a tree, the water first collects on the leaves, branches, and trunks and is either evaporated or absorbed. Some of the rainwater never even hits the ground. That sort of initial crash pad delays the onset of initial water surges, and reduces the volume of peak flows and flash floods. The water that was absorbed in the soil near the tree is transferred from the earth and transferred up to the leaves, where it can evaporate.

Trees can intercept rainfall from 8% to 68% of a rainfall event, and sometimes higher, depending on the species.5 Trees also manage heavy rainfalls through the process called Transpiration. The rate at which trees transpire is different for different species, and only recently have studies been attempting to quantify the rate. “A mature tree can, on average, transpire 100 gallons of water every day”6. In addition to interception and transpiration, trees also increase soil infiltration rates and overall infiltration capacity through the growth of tree roots, and the decomposition of roots and leaf litter.

Finally, trees have proven to be extremely successful at removing pollutants from stormwater. Bioretention systems planted with trees have been shown to be a best practice, and more research is proving tree plantings to be a best practice7.

Key Steps to Successful Urban Tree Plantings

Right tree, right place: Make sure you consider how big the tree will be when it is at its full capacity. Will it be 30 feet or 100 ft tall? Will it be 10 feet or 50 feet across? If you are planting a tree near a power line, or close to some other building or sign requiring visibility- take notice and plant accordingly.

Also consider the horizontal needs of a tree. Trees need enough space for their roots to grow as mirrored by their canopy. Which means, do not plant a tree sapling in a 2’ x 2’ cement box and except it to be living a year or two later. Make sure the full growth size of the tree you are planting matches the space that is available.

Consider the soil: It is important to consider the soil of where you want to plant trees. Many urban soils are extremely degraded, compacted or even contaminated and require significant remediation before it is ready for a tree to thrive there. First, have the soil tested. Second, depending on the results, make some decisions. If the soil is heavy clay, make sure to work with a broadfork to break up soil to make room for water, roots and air to move through the soil.

Another option that is being used to integrate trees and pavement is a designed soil medium called Structural Soil which can be compacted to pavement design & installation requirements, yet allows for root penetration and optimal tree growth.

However, if you can plant trees in natural soil with adequate space for its growth, a good rule of thumb for prepping the soil for urban trees is to top dress 1-2 inches of compost, rip to 1 foot, top dress with another inch of compost, and 2-3 inches of woodchip mulch and prepare an 8 foot diameter tree rings, and let the mycelium get to work!

Know that whatever steps you take to help repair the soil and plant a tree, you are improving the soil. An established tree’s roots can help to break up compacted soils and build organic matter as it draws carbon from the atmosphere. The increase in organic matter of the soil, increases soil’s water holding capacity- again strengthening its resiliency when facing heavy rainfalls.

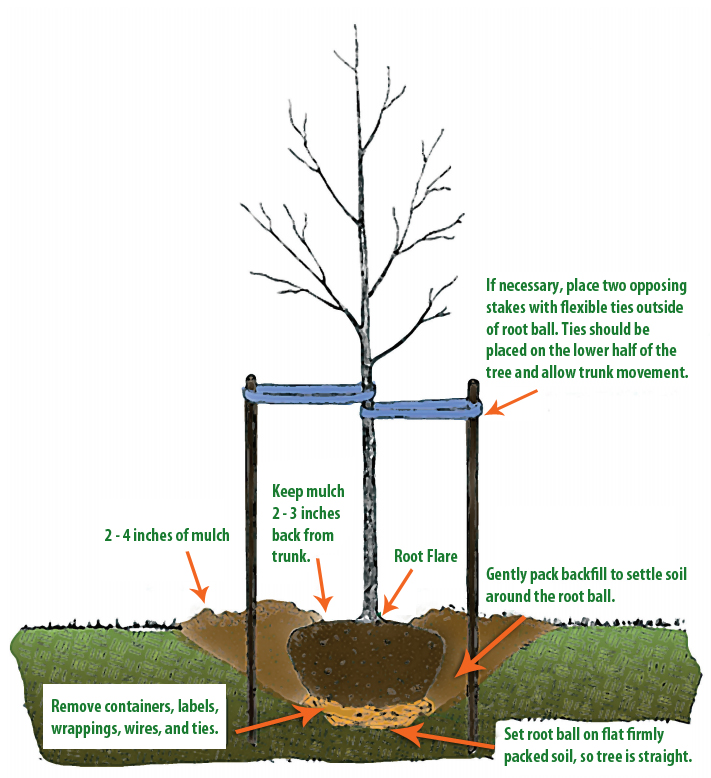

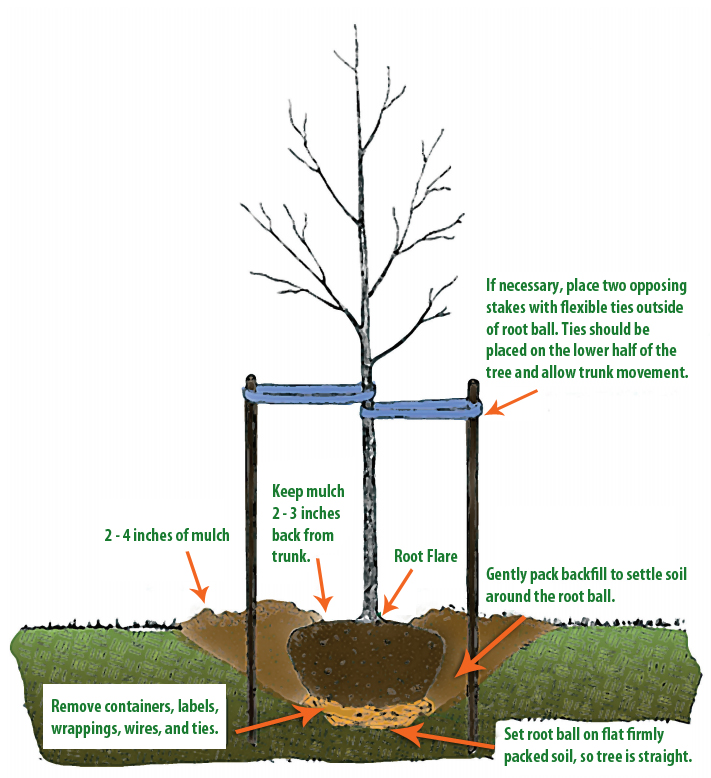

Plant a tree correctly: Go around many cities and towns and you will see trees with volcanoes of mulch piled around the base of their trunks. People do this thinking they are giving a tree what it needs. Little do they realize that by “volcano mulching” or piling mulch high up on the base of the trunk, you are actually damaging a tree’s ability to transpire properly. It is more likely to be susceptible to disease, decay, and potentially even result in strangling itself through girdling advantageous roots. That being said, the same is true for planting a tree. Do not plant it to deep. A tree’s root flare (the base of the trunk that curves out into the roots) must be level with the ground, and then a donut shaped circle of wood chip mulch should be placed around the tree leaving the root flare open to the air and able to breath at least a fist width distance from the base. See Image C for more details.

Anticipate the Water Management Needs: If you track or research the climate trends in your area, you may be able to anticipate about how much water you may need to manage on-site. Start by assessing how much water any pre-existing trees on-site are managing. One way to do this is using a tool like i-Tree8 which allows you to assess how much stormwater a tree may be intercepting by inputting its location, species, size, and condition. Comparing the number of how much water is already being intercepting, and how much water you must anticipate in an extreme moment, you may base your urban tree specie selection on that.

It is important to note, however, that even if your region expects higher rainfall, it is essential to have a water maintenance plan in place when planting new trees in the city. Newly planted trees are experience transplant shock and can require up to 15 gallons of water a week for the first three years after planting! So be ready to have a watering plan for trees in between heavy rainfalls to ensure their long-term thrivelihood.

A NOTE ON SPECIES SELECTION

The following list of trees (though some are more often considered shrubs) are all species that tolerate drought to flood conditions in a more temperate climate. Depending on your site, some varieties will thrive more than others. These species were chosen for their diversity in function from stormwater management capabilities, edibility/usability, wildlife habitat, beauty, and adaptability. They are as follows: Willow, Downy Serviceberry, Dogwood (Flowering, Red-osier, Yellow Twig), Eastern Red Cedar, Black Gum, Oak (Swamp White, Overcup, Chestnut, Nuttall), Black Walnut, Elderberry, Plum, American Hazlenut, Redbud, Sugar Maple, and Paw Paw. Check out the End Notes for more tips on selecting urban trees for transitioning climates9.

END NOTES:

1. The WATER Institue (Watershed Advocacy, Training, Education and Research) is a project of the Occidental Arts & Ecology Center in Occidental, CA. www.oaecwater.org. See Brock Dolman’s article “Watershed Relationships” In the Winter 2010-11 issue of Permaculture Activist # 78 for a more in-depth discussion and explanation of watersheds.

2. Trubek, Anne. “Money Does Grow On Trees: Canopy Cover Reflects Income Inequality.” Belt Magazine. http://beltmag.com/money-trees/

3. The Cleveland Tree Plan, 2015, http://www.sustainablecleveland.org/celebration-topics/2017-vibrant-green-space/the-cleveland-tree-plan/

4. The Cleveland Tree Plan, 2015.

5. Stormwater Management Benefits of Trees by Stone Environmental, Inc. http://www.vtwaterquality.org/stormwater/docs/sw_gi_tree_benefits_final.pdf Many additional resources can be found in this article as well, including more on tree selection, siting and planting, more on engineered systems for trees, and soil restoration resources, among others.

6. Stormwater Management Benefits of Trees.

7. Stormwater Management Benefits of Trees.

8. “I-Tree Design v 6.0.” i-Tree: Tools for Assessing and Managing Community Forests. http://www.itreetools.org/design.php i-Tree Design is also useful for assessing and understanding other tree benefits related to greenhouse gas mitigation, air quality improvements, and energy usage reduction. i-Tree Eco can be used for quantifying annual avoided runoff of trees. i-Tree Hydro can be used to quantify hourly and total changes in stream flow and water quality based on vegetation and impervious cover.

9. More tips for plant selection can be found at: Urban Forest Adaptive Planting List with consideration given to the warming climate. “Trees for 2050” Chicago Botanic Garden http://www.chicagobotanic.org/plantinfo/tree_alternatives; “Plants and Your Stormwater Control Measures.” Restoration and Recovery. http://rrstormwater.com/plants-and-your-stormwater-control-measures

CAPTION FOR IMAGES:

Image A: Combined Overflow System diagram, sourced at “Combined Sewer”, Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Combined_sewer

Image B: How Rain Gardens Work, courtesy of Lauren’s Garden Service, www.laurensgardenservice.com.

Image C: How to plant a tree. http://actrees.org/resources/local-resources/how-to-plant-a-tree/ as borrowed courtesy of International Society of Arboriculture.

AUTHOR BIO:

Diana Sette is a Certified Permaculture Teacher and Designer working primarily in Cleveland, OH, after almost a decade of growing in the Green Mountains of Vermont. She serves on the Board of The Hummingbird Project (hummingbirdproject.org) and Green Triangle (greentriangle.org), two permaculture-based non-profits working locally and abroad. Her work in social and urban permaculture is centered at Possibilitarian Regenerative Community Homestead (PORCH) and Possibilitarian Garden (Facebook: Possibilitarian Garden) in Cleveland, OH.

And not just careful, trip-weary harvesting of hardy ageratum pollen by monarchs on their way south.

And not just careful, trip-weary harvesting of hardy ageratum pollen by monarchs on their way south. No, the real disco atmosphere—one imagines a sparkling ball and an unlimited supply of rave—occurs just above my patch of boneset (Eupatorium Perfoliatum)*. Wasps (especially), bees and other insects lurch onto boneset’s little white flowerettes, hold their position for a split second, then burst off to the next plant. They’re just so excited. And the variety! Big wasps, little wasps, bees, moths, butterflies, little flying things I don’t have a name for. Rarely do any of the feeders pay attention to their companions (though I have seen smaller, more aggressive mason wasps deliberately knock more cumbersome digger wasps off a flower). A true feeding frenzy.

No, the real disco atmosphere—one imagines a sparkling ball and an unlimited supply of rave—occurs just above my patch of boneset (Eupatorium Perfoliatum)*. Wasps (especially), bees and other insects lurch onto boneset’s little white flowerettes, hold their position for a split second, then burst off to the next plant. They’re just so excited. And the variety! Big wasps, little wasps, bees, moths, butterflies, little flying things I don’t have a name for. Rarely do any of the feeders pay attention to their companions (though I have seen smaller, more aggressive mason wasps deliberately knock more cumbersome digger wasps off a flower). A true feeding frenzy.