by Elsa Johnson

As I drive about, during this busy time of the year, observing the annual riotous explosion of nature and the never-ending human need to keep nature in check (all those tightly trimmed gumdrops and bowling ball shrubs — all those landscapes of polka-dot plants adrift in a sea of mulch)

I wonder: how did our sense of what a landscape or garden should look like come about?

How much do the examples of traditional great landscapes and gardens influence us? – such as the naturalistic English landscape; the elaborate, contrived, formal estate gardens of the Renaissance and early enlightenment Europe; the elaborate, formal pleasure gardens of the Middle East and Asia; the naturalist seeming Japanese Gardens, that are actually deeply artificial – these all remnants of the gardens of the economic and political elite through time . The gardens of more ordinary people endure less well, alas – but, still, we do have a picture in our heads when we say cottage garden, herb garden, kitchen garden, commons (that small parcel of shared land around which a village grew).

What do these diverse examples of landscape and garden have in common? I believe that what informs them is a human need to order toward simplification what we see as disordered nature.

There are exceptions: we know (today) that the indigenous peoples of the Amazon River basin traditionally lived in what we now acknowledge as a food forest, which was and is – where it still exists – a place where these peoples live in accord with the seasonal productivity of the forest. The food forest is an example of a complex system (rather than a simple one), shaped (somewhat) by the people who lived/live within it. To western sensibilities the food forest as garden was and remains largely invisible because the organizational principles underlying it are not simple and thus not readily visible.

More often we see that he human need to impose order – to hold a thing quiet in time — is directly opposed to nature’s inherent mutability. We create outdoor spaces and then work hard and spend a lot of money (and endure a lot of noise) to keep them from changing one iota over time, in a climate (northeast Ohio) where garden or lawn, left untended for even one year, quickly begins the process of returning to forest. Nature is about fecundity.

Nature unchecked.

Gardening is about controlling fecundity, holding it in check. We want the garden to behave like architecture – a thing that once built and decorated, does not change. Hence the gumdrops, bowling balls, and polka-dot plants adrift in a sea of mulch. But, there are other options, ranging from naturalized to a careful balance of order and nature.

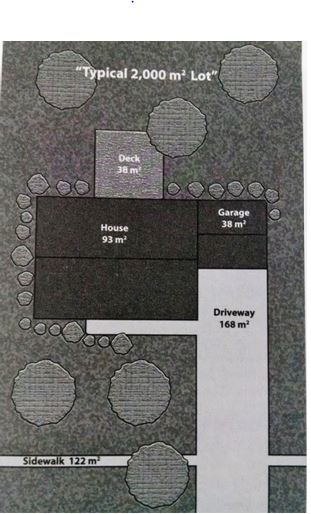

See naturalized gardens below:

See a balance of natural and man-made below:

Underlying the need to hold time quiet is the fact that simple landscapes are easier to maintain for the non-gardener, and I include as non-gardeners most of the landscape crews to whom we outsource the maintenance of our gardens, who, largely untrained, can only repeat what they see and are given or told to do. We do not hire gardeners: that word implies knowledge about the plant world. Instead we hire maintenance crews – most of whom have no specialized knowledge beyond how to mow, trim and edge in a flurry of action and noise (none of it carbon neutral), and as quickly depart.

Some friends of mine recently sold their large house in its richly complex landscape which had been developed over a decade of time. When the realtors came to take a look at the property before putting it on the market, they said no one would want that landscape, and urged that the landscape be simplified (meaning, rip a bunch of stuff out and replace with mulch), the implication being that no one wants a visually and ecologically complex landscape. No one, of course except the birds and the bees and the butterflies and all the other beneficial insects.

There is naturalistic, and then there is something that is just too much like real nature. What do you think? We’d like to hear from you.